|

Winter 2005 (13.4)

Pages

64-67

Aydin

Vahidov

In Search

of Goodness:

Even in the Deep Freeze of a Siberian Labor Camp

by

Aydin Vahidov, in exile for 7 years

Aydin Vahidov (1925- ) was a victim

of Stalinist Repressions more than half a century ago. Arrested

in 1948, he served seven years in prison camps in exile. The

charges against the group were trumped up, exaggerated and carried

severe punishment. Somehow, he survived. Aydin Vahidov (1925- ) was a victim

of Stalinist Repressions more than half a century ago. Arrested

in 1948, he served seven years in prison camps in exile. The

charges against the group were trumped up, exaggerated and carried

severe punishment. Somehow, he survived.

The truth was that Aydin was involved with Ildirim, a group of

students, who were advocating a wider official use of the Azerbaijani

language in a society that was fast gravitating towards the prestigious

Russian language of the Soviet Union.

That's all. And these would-be-activists really didn't succeed

at doing anything because the atmosphere was so repressive that

they felt compelled to disband the group - four years before

their arrest.

Though Aydin readily admits that nothing they did would ever

go down in the annals of cultural history in Azerbaijan, he remains

convinced of the integrity of the group's convictions. "We

were on the right track," he insists. "And we proved

that Azerbaijani youth could fight for their rights."

We found one of the distinguishing characteristics of Aydin's

life to be his persistence in living in the present, not the

past; and concentrating on the positive, not the pain. Perhaps,

it was merely a survival technique but it stood him in good stead.

Today, he reflects upon his experience in exile, both personally

and professionally, as the foundation for his career in engineering

in which he continued to be active until age 79 when he retired.

We interviewed Aydin in his home in November 2005. He was ill

at the time. He shared his memories with us from his bed, too

weak to raise his voice above a whisper. His mind was strong.

His memories, vivid. His approach, pragmatic. A realist, Aydin

didn't gloss over the harshness of exile, but neither did he

romanticize it.

The more he realized that we really were keen to know his story,

the more he kept remembering anecdotes that illustrated the multi-dimensional

aspects of life in exile.

Of particular note was the time when he had just arrived in one

of the camps and was feeling the heavy burden of his loneliness.

It was in such a needy moment that he overheard another prisoner

singing an Azerbaijani folksong. He knew the tune, and picked

up on it, whistling back the melody; thus, enabling the two prisoners

to meet.

Deep appreciation goes to Aydin's wife Zoya and daughter Gultakin

for facilitating our interview. Of the seven Ildirim members

who were arrested in 1948, only Aydin and Gulhusein Huseinoghlu

[Abdullayev] were still living in late 2005 and early 2006 when

we were researching people who had personally witnessed the impact

of the Stalin's Repressions.

I was born on July 11, 1925, in Baku

to a family of government workers. After finishing secondary

school, I was accepted at Azerbaijan Institute of Oil and Chemistry

where I was always an "A" student. I graduated from

Faculty of Mechanical Engineering. I was born on July 11, 1925, in Baku

to a family of government workers. After finishing secondary

school, I was accepted at Azerbaijan Institute of Oil and Chemistry

where I was always an "A" student. I graduated from

Faculty of Mechanical Engineering.

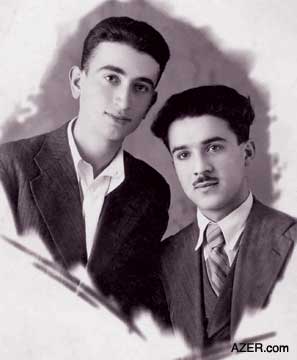

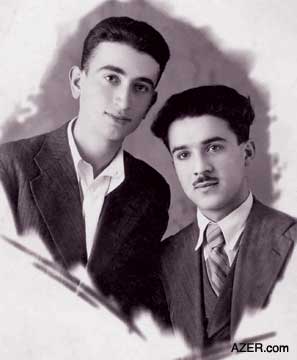

Left: Both Aydin Vahidov (left) and Kamal

Aliyev were members of the Ildirim group. In 1944 as students,

they wrote to the poet Samad Vurghun for support for more widespread

official usage of Azeri. Vurghun turned the letter over to the

KGB and the Ildirim members were arrested in 1948. Aydin and

Kamal were each sentenced 10 years of hard labor in Siberian

camps. Photo: Courtesy of family of Aydin Vahidov.

In 1944, I joined a student group called "Ildirim"

(Lightning), which had just been established. In those years

the situation among students was very tense.

There were anti-Soviet, anti-government sentiments seething under

the surface everywhere. But those who opposed the government

were not able to unite and act. Students needed an organization

so that they could formulate their ideas and plan for action.

At that time, Gulhusein Huseinoghlu

[Abdullayev] and Ismikhan Rahimov were studying at Azerbaijan

State University and undertook to establish such an organization.

As students, we felt that government workers, intellectuals -

artists and writers - shared our ideas, but everyone was too

paralyzed with fear of the repressions of the 1920s and 1930s

to do anything.

The first person to step forward publicly was Samad Vurghun.

We could sense this from a speech he made to the Writers' Union

in 1943. So Gulhusein and Ismikhan wrote Samad a letter, requesting

his help. But he betrayed us and took our letter and passed it

to Mir Jafar [Baghirov, Stalin's "right hand man" in

Azerbaijan in his position as First Secretary of Central Committee

of Azerbaijan SSR Communist Party]. In turn, Mir Jafar gave the

order and the officials came looking for us.

We

yearned for the development of Azerbaijan. We wanted to be able

to use our language freely under all circumstances. At that time,

everything was in Russian. We

yearned for the development of Azerbaijan. We wanted to be able

to use our language freely under all circumstances. At that time,

everything was in Russian.

Left:

Aydin Vahidov (lower left

corner) with a group of Azerbaijani friends in a Siberian labor

camp in 1951. Aydin worked there as an engineer. Photo: Family

of Aydin Vahidov.

Children were being taught Russian, and many were unable to speak

their own mother tongue. Russian had already become the prestigious

language of choice in our country.

I myself knew the Russian language and Russian literature very

well. But I was concerned about uneducated people who didn't

know it and, therefore, could not stand up for their rights and

could not advance in their careers.

Back in the 1930s, we were using a modified Latin alphabet in

Azerbaijan much like the one we have adopted since independence

[1991].

Azerbaijanis had opted to replace the Arabic script, which we

had used for hundreds of years, with Latin. I'm glad I've lived

long enough to see the alphabet of my youth readopted as the

official script of the country. These were the things we were

pushing for as university students more than half a century ago.

These were the ideas that landed us in prison and for which we

suffered unbearably.

The Ildirim group - actually, we weren't against the Soviet government.

Actually, we weren't even involved in politics. All we wanted

was freedom to use our language officially.

Ildirim Meetings

We used to meet in the Saadat Sarayi [Wedding Palace]. Back then

in the 1940s, this building [which had been the palatial residence

of Oil Baron Murtuza Mukhtarov] was used as a university. I think

it housed the Institute of Foreign Languages. Our group would

meet there in the afternoons around 5:00 or 6:00 o'clock when

everyone had gone home. We also used to gather at some of the

homes of our relatives. We wanted so much to publish a newspaper

in Azeri to promote the use of our language. Keep in mind that

in 1946, the efforts in Southern Azerbaijan [Iran] in trying

to gain independence influenced us. Just as Pishavari wanted

freedom for the Azeri language there, Ildirim wanted the same

in Northern Azerbaijan. Without a doubt, the events in Southern

Azerbaijan had a strong impact on the thinking of the youth in

Baku.

But those were dangerous times. We were afraid to confide in

others about our plans and ideas. Young people were scared to

do anything to counter the Soviet government. Keep in mind that

hundreds of thousands of people had already been arrested, starting

in the late 1920s. Then there were the Stalin purges of 1937-1939.

Basically, the only thing that Ildirim ever did was to write

a letter to Samad Vurghun. And that small gesture was exactly

what got us all arrested. The letter that we wrote to him in

1944 somehow managed to end up with the KGB in 1948. Who knows

why it took so long.

But our activities didn't last very long. Back in 1944, after

we didn't receive any reply of support from Vurghun, we got very

disappointed and disbanded the group. Looking back on our efforts,

I admit that our activities did not impact the cultural development

of our country, but we did prove that Azerbaijani youth could

fight for their rights.

In those days it was very difficult to trust other people. If

there were three people working together in one room, you could

be sure that one of them was an agent. It's hard to imagine the

tortures that were done to people. There was no end to rumors

that were circulating - stories about victims being thrown into

the sea off Nargin Island weighted down with rocks tied around

their necks.

Shortly before I was arrested, I could sense that I was being

followed. Finally on November 5, 1948, they arrested me.

I remember it so clearly - that night I was arrested - even though

it was more than 50 years ago. It was after midnight - around

4 a.m. I was with my wife. We had only a one-room apartment.

They showed me the order for my arrest and then shoved me up

against the wall. They searched everywhere - three of them. And

then they confiscated everything.

The trial didn't take place for five months while we all languished

in the KGB prison - a five-storied building hidden inside the

courtyard of the KGB building down by the sea. There was a prison

inside there. That's where we were kept. Myself, I wasn't tortured.

Our families were not able to visit us while we were in prison

but they were allowed to bring parcels. I was married and had

a daughter. I also had four brothers and three sisters. All of

the members of Ildirim were together in prison. There were other

political prisoners, too, but I didn't know them.

They finally scheduled the court session for the following spring

on March 21 and 22 [which happened to be Novruz, a day that is

traditionally one of joy]. Our family members were not allowed

to be present. It was a closed, secret trial. The government

provided us with a lawyer, but he offered no defense. It was

a farce.

Papers had already been prepared for us at the trial and we had

no choice but to sign them, alleging our guilt. They made us

admit to being members of an anti-Soviet organization. They further

accused us having relationships with Turkey, which wasn't true

- as if we were trying to separate Azerbaijan from the Soviet

Union and unite with Turkey. I was sentenced to 10 years of hard

labor.

On the Train into Exile On the Train into Exile

At first, the members of Ildirim were sent to Rostov in Russia

where we stayed for four days.

Left:

Aydin Vahidov with his family:

his wife Zoya and two daughters Gultakin (older) and Mehriban.

1971. Photo: Family of Aydin Vahidov.

Then we were separated and I was sent across Central Asia to

the city of Magadan [a port city in Eastern Siberia on the Pacific

coast near Japan, which served as a major transit center for

prisoners being sent to labor camps]. It was extremely cold there

but I like that weather.

It was such a long journey from Azerbaijan to Magadan on the

Pacific coast by train. Eight of us had been together in the

same compartment. A ninth person accompanied us. It was clear

to us that he was a spy.

I worked as an engineer there and so, unlike many others, I was

relatively free. Once a month we had to register with one of

the committees. They wanted to make sure that we were still at

the camp. I worked in a factory and developed very good construction

skills. I was sent to some of the largest labor camps in the

Soviet Union - Mordovia [southeast of Moscow in the Central Volga

Region].

I worked in Potma as a mechanical engineer. Yes. I worked night

and day with all my strength. And I continued to do so all of

my life. I was 79 years old before I retired. Throughout the

years, I've been involved in the construction of so many buildings.

I never hated the Soviet Union. Even after coming back from exile,

I was very active in the community and became the director of

a machine factory.

The Right Thing

Still despite everything I had to endure during those horrendous

years, I never had any regrets about joining Ildirim. We were

doing the right thing. We wanted Azeri to be spoken in all offices,

and for all official correspondence to be carried out in Azerbaijan's

own language. We were on the right path. Under the same circumstances,

I would do it again.

Even during those times when Stalin's portraits and statues were

all over the country, I used to predict that the day would come

when Stalin would be disgraced. And that's exactly what happened.

There's an expression: "You can rob a nation of its money

and its land. You can even kill its people, and the nation will

still live on. But if you take away its language, it will die."

In the 1930s and 1940s, not many Azerbaijanis knew Russian very

well. And those who weren't fluent in Russian were not able to

demand their rights, get good jobs, or progress in their careers.

Ildirim wanted people to have a chance to better their lives.

That's why we demanded freedom for our language. You might say

that the Ildirim group fought for moral freedom, not political

freedom - moral freedom from the Soviets. I really was never

against the Soviet government itself.

Hardships in the

Camps

When I think back on the camps - I really don't like to focus

on the bad memories. It's so painful for me. Why talk about bad

memories? One of the biggest problems we faced in the camp was

that we didn't have enough food. There was never enough bread.

There were times when we couldn't even think about the future.

We lost all hope that we would ever be released. There were times

when we didn't even know if we could make it through the day.

People who had been branded as "Enemy of the People"

were being shot all the time. We were all just waiting to die.

There were many Japanese and Englishmen there who worked in the

same city. They were very intelligent people. I learned some

English so that I could converse with them. I also learned some

German but then I was assigned to another labor camp.

Professional Engineer

The most significant thing that happened to me during my years

of exile was that I became a professional in my field. In labor

camps there was nothing else to do but work. You have to use

such opportunities. You have to obey the rules. Those labor camps

gave me both life and work experience as an engineer in the camps.

My family tells me that sometimes at night I talk in my sleep

about things that happened in Magadan. Sometimes, I even mention

the names of some of the people who lived there with me. Once

I was under heavy medication, and it seems it affected a certain

part of my brain, which brought back so vividly the painful memories

of my exile. When I'm ill, memories of that period of my life

come back to haunt me.

Secrets in the Family Secrets in the Family

My wife and I didn't even tell our daughters that I had been

a member of an anti-Soviet organization and denounced as an "Enemy

of the People".

Left: Aydin's wife Zoya on the occasion of

her 70th Jubilee. 2004. Photo: Family of Aydin Vahidov.

We never talked to our

children about these experiences until after independence [1991].

Sure, my children knew that I had been arrested. But they didn't

know the reason. They told me later that it had been very difficult

for them to understand how such an honest person was capable

of carrying out a crime and getting arrested. Simply, they didn't

know why I had been arrested. We hid the documents related to

my arrest. When we sat down with our children to talk about these

things, they were shocked.

They knew that Ismikhan and I were good friends, but they didn't

know the history of our friendship. He also was sentenced to

hard labor.

We were afraid that if we told our children about these things,

they might casually mention them to their friends, and it would

get them into trouble. Even though my [second] wife and I didn't

get married until 1960, which was seven years after Stalin's

death, we were still frightened that something could happen to

our children because of me. The greatest difficulty during exile

was being away from family and friends. I wasn't able to write

them, nor could they write me. My wife divorced me. We had one

daughter. It was my parents who took care of her for me.

Souvenir from seven years of exile? Yes (laughing), I still have

a few photos. But mostly I have only my memories and nothing

else. Upon my return, I enrolled in the university. I was rehabilitated

in 1956 and remarried in 1960.

Actually, my wife's family was against our marriage but her brother

Tofig Hasanov used to work for the KGB and he managed to get

hold of my trial papers and read them. He was convinced of my

innocence and so her family agreed and that's how I married Zoya.

In fact, today we celebrated our 45th anniversary. We were married

on November 10, 1960.

"The greatest thing that we gained from Stalin was our thirst

for freedom. We suffered indescribably." After those many

years of repression, Azerbaijan started moving towards freedom.

People hold varying opinions about Stalin. Undoubtedly, he was

a smart man, but he took us down a wild, chaotic path. In the

end, so many people died.

|

"The greatest

thing that we gained from Stalin was our thirst for freedom."

--Aydin Vahidov,

who spent seven years in Siberian labor camp.

|

Stalin's Death

Concerning Stalin's death: I'll never forget the day that we

learned that Stalin had died [in March 1953]. I was in a labor

camp where political prisoners and criminals were mixed together.

The political prisoners were relieved when they heard the news

of his death. Curiously, the criminals were not. After all, Stalin

was a criminal, too. Myself - I was happy. It was like I could

again hope one day to be released. That's when I started making

plans about what I would do when I got back home. I wanted so

much to continue my education and work.

But the most important thing is for our own Azerbaijani people

to learn about this period in our history. Our people should

know that there were people who fought for the independence of

our republic - for their independence. We always knew that Azerbaijan

would be independent one day.

An Azeri Melody

Let me share with you one episode from those days that I've never

forgotten. We were on the train traveling between Baku and Rostov,

and then heading eastward to another camp where political prisoners

were being kept. When we finally got off the train, I was separated

from my friends. They put me in a car and took me to a labor

camp.

They had a rule: we all had to pass one-month quarantine separated

from the other prisoners so that if anyone had an illness it

wouldn't spread like a contagion through the camp. All those

people with me were, indeed, criminals. I was the only Azerbaijani.

I felt so alone. Once while standing near the window of our hut,

I heard someone singing a song that I knew so well in Azeri (Aydin

sings):

How can I not love your beautiful

face?

How can I not love the mole on your cheek?

Azeri version of the poem

I answered by whistling back

the melody. I was so curious to find out who was singing this

song. I soon discovered that it was my old friend - Musa Abdullayev

- one of the members of our Ildirim group. All of us had been

separated and sent to different camps years earlier. But here

he was again. And we had found each other. I asked permission

from the guards if we could speak together. They let us. And

that's how Musa and I found each other in that camp and were

able to enjoy each other's friendship for a while until I had

to move on to another location. It was a memory that I would

cherish for the rest of my life.

Back to Index

AI 13.4 (Winter 2005)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|