|

Above: Gulhusein Huseinoghlu as a high school student in 1941, as a university student in the mid-1940s, and as a prisoner in exile (September 2, 1954). Photos: Family of Gulhusein Huseinoghlu. I wasn't able to tell anyone

about my arrest - not my family, nor my wife. I was married and

had a daughter. She was one year old at the time. Now she's 52.

I couldn't inform anybody that I had been arrested. My family

found out later from the university staff.

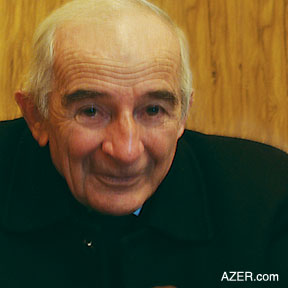

Above: Gulhusein Huseinoghlu, imprisoned as a university student in the late 1940s, is one of very few Azerbaijanis who are still alive who experienced the trauma of Stalin's Gulag - a vast network of labor camps that extended from one end of the Soviet Union to the other, from the Arctic region to Eastern Siberian. Gulhusein, 83, intends to write his memoirs but, in the meantime, he kindly agreed to let us interview and share his story with our international readers in December 2005. Photos: Blair. So, after Ismikhan confessed everything, there was no use my denying it. Nor can I blame Ismikhan because the NKVD employed such methods. Who can hold out against them? Haji was the first one to be arrested, but then when Ismikhan was arrested, he confessed everything in Haji's presence and so Haji confessed, too. And after two people had confessed, they arrested the rest of us as well. I didn't confess anything for 10 days, but then they brought Haji and told me there was no use resisting anymore. The interrogation took place in a large room. The interrogator was sitting at one end of the room and I was at the other end - an uncomfortable distance away. The chair that I was sitting on had been nailed to the floor. Maybe, in the past, someone had tried to hurl it at the interrogator. Maybe that's why they attached it to the floor. I don't know. The interrogator would ask questions and I would answer. But I was sitting so far away from him. Since we were part of the Soviet Union, all the documentation of the interrogation had to be written down in Russian. The poor guy who was drilling me wasn't very literate and didn't know Russian well enough. So I was correcting his sentences so that it would be grammatically correct. Imagine! He was interrogating me and I was correcting his Russian! Once during one of the sessions, Colonel Padarov, head of the interrogation service of the NKVD entered. The interrogator stood up, but I didn't. He asked the interrogator if I were giving him any trouble. "Everything is in his stomach," he replied, meaning that he couldn't get a word out of me. So, Padarov turned to me and threatened: "I'll make your mother cry." "That's not a difficult thing to do," I replied. "My mother has been crying ever since the day you arrested me - her only son." He swore at me. And I shot back: "You come in here wearing that uniform, and you think you're a colonel or something big. But no, you're not free either. I'm a slave, but I'm an ordinary slave. You're a colonel slave. We're against slavery here." I realized that they would kill me so I wasn't afraid of saying things like that. But, fortunately for us by 1948, Stalin had passed a decree bringing a halt to all executions. Otherwise, we would have been shot. They had already shot so many people. The world community had started to complain about it. Already the United Nations had been established. In addition, local and foreign newspapers started propagating about the humanism of Stalin, insisting that the Soviet Union had stopped the executions. Thanks to that new ruling, we were alive; otherwise, we would have been shot, especially me since I was the founder of Ildirim. Instead, I was sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment. Our camp was located in Eastern Siberia ("Vostochniy Sibir" in Russian) close to the Baykal Lake in the forests. This was a huge network of camps, covering territory that extended more than 300 kilometers. We arrived there by train. It was such a long journey. The train would only move when the tracks were empty, and when they didn't interfere with the regular schedule of trains. So, sometimes our train would stop in the middle of nowhere and remain on the sidings, sometimes up to three days. The carriages were called Pulman, but the truth is that they were mostly used to transport cargo: they were boxcars. Each boxcar could carry about 60 people. They were outfitted with three levels of bunk beds. I always chose the top level so people wouldn't come and sit on my bed. I paid attention to things like that. People used to gather on the lower bunks and sit there all day long.  Left: Gulhusein Huseinoghlu returned from Siberian labor camps in 1956 after being imprisoned for seven years. He married and began a new family. Sitting (left to right): Gulhusein Huseinoghlu, daughter Aytak and wife Almaz. Standing: sons Ughur, Yalchin and Toghrul. March 29, 1974 in Baku. Photo: Family of Gulhusein Huseinoghlu. None of the other members of Ildirim were assigned with me to the same camp. Only once during those years of exile did I ever see any member of our group. Once Ismikhan Rahimov arrived in the same camp and we were together for three days, but then they sent him away. It seems he had been brought there by mistake. Later when they discovered that we were from the same organization, they separated us. But it was great to see him - even for a few days. In each camp, they were officers assigned to investigate things like that. There were about six or seven other Azerbaijanis in my camp as well. We used to speak Azeri together. Among ourselves, we could speak any language we wanted to. There were Englishmen, Germans and so many other nationalities - mostly prisoners of war. Once I counted 78 different nationalities assigned to our camp. It was a large camp. I'm not sure how many people might have been there - maybe 1,500 or even more. At this camp, prisoners were assigned two different kinds of work - lumbering or mining. I didn't work in the quarry much. Mostly, I used to work, cutting down trees all day long. While in exile, we used to wear woolen vests. Our coat had cotton padding inside. We would get up at 6 a.m. Of course, it was still dark outside. Breakfast was at 7 a.m. They would serve soup for breakfast. The food barely kept you alive because of the strenuous workload. They would weigh out 700 grams of brown bread for each prisoner each day. Sometimes, it wasn't baked very well. Actually, it was enough for me because I had never been a big eater even before I went to prison. For example, this morning I haven't even eaten 50 grams of bread. I usually have a substantial lunch. In the camps, they would dish out two ladles of soup into our bowls. It was so little that sometimes people would just drink it directly from the bowl and then end up being hungry for the rest of the day. Myself, I would divide the bread into three portions to eat as three separate meals. It was up to you if you wanted to do it that way and hold back a portion for lunch and dinner as well. I usually divided the bread into three parts and tucked it away in the pocket of my coat. There was an Estonian lad there in the camps, who was good at sewing. He sewed a pocket for me so I could carry my bread inside my pocket. You didn't dare leave it in the barracks; someone might steal it. What could you do to such a person even if they confessed to eating your bread? He was hungry. You couldn't kill somebody over 100 grams of bread. Therefore, to avoid such a crisis, I used to carry the bread in my vest pocket. Some people didn't have the discipline to do that and they would just eat all of their bread in the morning and have none left for other meals. Our plates and cups were made of aluminum, and we used to carry them around with us. We worked until 1 p.m. They would bring our lunch out to the forests where we worked, but the ration of bread had to last the whole day. Then we would resume working until 6 p.m. and head back to the camp before it got dark. Camp was located about 5-6 kilometers away along a road through the forests. After arriving back at camp, we would wash up for dinner. If you had worked hard during the day, they would give you additional porridge. It was mostly barley porridge. Those who had fulfilled their work quota 105 percent that day would get an extra spoonful of porridge. Those who achieved 110 percent got two spoonfuls. It went like that. If you didn't meet your quota, then you wouldn't get any extra porridge at all. They would give you the minimum. That was it. Nothing extra. After dinner, we had a little time for ourselves. We could walk around in the yard. But by 9 p.m., everybody had to be back in his own quarters and the barracks were locked. They even closed the doors separating the barracks inside the building. If there were five barracks in a single building, all of them would be locked separately. Each night there would be roll call to make sure that all the prisoners were accounted for. They would call us by our last name. We had numbers as well, which were written on the back of our vests and coat. My number was "YA-126" ["YA" represents a single Russian letter]. I had turned 25 years old on the exact day that I was sentenced to 25 years of exile. In the end, my sentence turned out to be seven years because Stalin died in 1953 and our case was re-examined. They determined that the verdict had not been just and that we should have been sentenced for five years, not 25. Since we had already been imprisoned for seven years, they released us immediately [May 1955]. The families of all of our friends, except mine, had constantly been writing to Moscow while we were in exile. So, after Stalin's death, the Supreme Court re-examined our case. I didn't write anyone. I still don't consider myself guilty - even now. I want always to be considered an enemy of anyone who tries to occupy my country. We just wanted to be free. So we were freed. A military officer with the rank of Major told me the news. I asked him if I would be able to start again writing and publishing my works as a member of the Writers' Union since I was a writer. He told me that my document did not deal with "rehabilitation". It merely decreased the number of years of imprisonment for us. But we would still be considered guilty and be labeled "Enemy of the People". I told the major that if that were the case, I didn't want to leave the camp. As I was still rather young at the time, he admonished me, "Son, I advise you to return to Azerbaijan and continue your struggle. You can't defend yourself here. Look, we allow you to write only two letters a year. I'll let you in on a little secret. We only send one of those letters, and we do that only after we find an Azerbaijani who can read and screen its contents. After all, you might disclosing the exact location of the camp in your letter." So, you see, they checked every single attempt that we made to communicate. That meant that most of our letters never ended up being sent. I guess that Major liked me or something because he was so sincere in telling me these things. He advised that since I couldn't prove that I was right with a single letter that I should continue my struggle in my own country. That was 1955. I asked him if I could go to Baku, as I didn't want to live somewhere else. He said, "Fine". Usually, they wouldn't let you return to a major city [most prisoners were settled 101 kilometers outside of major cities]. People who had been imprisoned or exiled had to settle somewhere out in the countryside. Miraculously, all of us from Ildirim were allowed to return to Baku. I specifically asked him about this because if I had to return to some other town, I didn't want to leave the camp. I would just stay there. Stalin's Death - 1953 I'll never forget the day we heard the news about Stalin's death. That was in March 1953. We were working in the forest. Guards were always watching us when we worked. We overheard them talking about Stalin's death and asked what had happened. There was one guard among them who was really nice to us. Some of them were human beings as well. So, he told us, "Congratulations, Stalin is dead." So, as soon as he said that, we threw our hats up in the air and shouted, "Hurrah!" We were so happy. The guards watched, but didn't say anything. We shouted and expressed how excited we were. Ismikhan's experience was so different. When he heard the news, he and the other prisoners with him dared not even show any expression on their faces. But we were exuberant in our joy. Crossing the Line Let me tell you another interesting story. I read about this in the newspaper "Vostochnaya Sibirskaya Pravda" (Eastern Siberian Truth) which we used to get. There used to be a line drawn around the place where we worked. We were not allowed to cross that line. If we did, even accidentally, a guard could shoot and kill us on the spot. He could even get a medal for doing so because it would show how vigilant he had been. Once the newspaper wrote how a guard had called one of the prisoners to come over to him. To do so, the prisoner had to cross that line. And yes, the guard shot him down. He had deliberately called the prisoner so he would be able to shoot him and get a medal because he could argue that the prisoner was trying to escape and he had prevented it from happening. So, one day our brigadier told me that one of the guards was calling me. I told him I wouldn't come to him. I was working and often the guards called the prisoners and ordered them to build a fire for them. It was freezing cold there and, of course, the guards got cold just like we did. For some reason, this guard had picked me from all the prisoners. He was calling for me. But I refused to go. So, the brigadier went and told him. Suddenly I heard that guard call out in Azeri, "Hey, Gulhusein, it's me calling you. I'm from the village neighboring yours in Azerbaijan." It turned out that he was from the region of Masalli, just like me. He was doing his military service and had been sent to serve in the camps. So after I realized who it was, I went over to him. He asked me to make a fire for him and we talked together for some time. He offered me some bread. Soldiers used to get white bread, not brown bread, like ours. So, he gave me half of his white bread. I talked to him until I had to go back to work. I only saw him that once. Never again. You see, in the midst of all these terrible things, there were incredible gestures of kindness. Anti-Soviet Sentiments You know, I can truly say that I was never depressed about my sentence. I knew why I had been arrested. Any government would have arrested me because I was deliberately going against the State. So, I was always strong. I had done something - that's why I was there. Again and again, I repeat: I resisted this system and that's why I was arrested. If I had not resisted, I would not have been arrested. I had been recognized as one of the best students in the university and awarded with a Stalin stipend of 500 rubles, which was later raised to 700 rubles. That was big money in those days. Despite all that, I resisted the system. I was also respected everywhere. But I did this because I loved my nation and didn't want our people to live like slaves. I'm anti-Soviet from head to toe. I'm against the exploitation of Russians of my country. I'm the enemy of anyone who tries to invade my country. I want freedom for my nation. When I started Ildirim - actually even before we got organized - I would take any person who was serious about joining our group down to the NKVD building. We would walk around it and I would ask them if they knew what that building was used for. I remember taking Kamil Rezayev there. He said he knew that it was a NKVD building and that people were brought there when they were arrested. I told him that the group that we were organizing would land us there if we ever got arrested. I asked if he were ready for that. And only afterwards did I explain about our group and invite him to join. He did, and it wasn't long before he saw that building from the inside. Inside the courtyard, there is a five-storied prison. The construction has been carried out in such a way that you can't see the inner building outside from the street. The building inside is one story lower and has a basement. Tunnels have been built which lead to the sea. This enabled the authorities to take the prisoners, load them into boats and transport them across the bay to Nargin Island where they would be shot. Return to the University Two months after returning from exile, I was re-admitted to the university as a post-graduate student. Prior to that, I had gone to the university, but they had told me that they could not re-admit me since I did not have any rehabilitation papers. They told me that I would have to apply for post-graduate studies and take the entrance exams again. I took back my application and told them that even if Lomonosov came back from the dead and took that exam under such conditions, he would not be accepted [Mikhail Lomonosov (1711-1765) was the Russian genius who made major contribution in numerous fields - literature, language, history and science]. I knew that they would not accept me under any condition until I had my rehabilitation papers. When they finally came [July 22, 1956], I met with the Rector, who was sympathetic and kept asking me who I had met in the camps and about the situation there. Then he asked me if I wanted to be re-admitted as a post-graduate student or as a teacher. I was foolish at that time and chose to enter as a post-graduate student. That meant that I would have to finish my studies in half a year but then I would be without a job for four months. But I was very proud and wanted to continue from the point where I had been interrupted. After graduating, I started writing and even though I didn't have a job for four months, I was being paid for my writing. It was while I was finishing my classes that I met my future wife. She was in her final year at school. I liked her and so I married her. We were married in 1956. She is still with me. When I returned, my beliefs

were even stronger than when I was arrested. I knew that I was

right. My people can't live under repression and invasion all

the time. We have to be ourselves. We must be free. If something

should ever happen again, I would stand up against it.

|