|

Winter 2005 (13.4)

Pages

80-87

Teymur Salahov

Deafening Silence: Waiting 18 Years for Father to Return Home

by

the Salahovs - brother and sister, Tahir and Zarifa

Zarifa

Salahova (1933-) is the founder of the Museum of Miniature Books

in Old City, Baku, which contains thousands of miniature books

that she had collected during the past 30 years. Her brother

Tahir (1928-) is recognized as one of Azerbaijan's most prominent

artists. He is the co-founder of the movement in Soviet Art known

as "Severe Style", which emerged at the end of the

50s and in the beginning of the 60s, as a reaction against Socialist

Realism. This philosophy of art suggested that everything was

going along fine in society. All people were happy, contented

and working for the progress of the nation. "Severe Style"

mirrored reality more closely, showing the sadness, loneliness

and difficulties that individuals faced under the Soviet system. Zarifa

Salahova (1933-) is the founder of the Museum of Miniature Books

in Old City, Baku, which contains thousands of miniature books

that she had collected during the past 30 years. Her brother

Tahir (1928-) is recognized as one of Azerbaijan's most prominent

artists. He is the co-founder of the movement in Soviet Art known

as "Severe Style", which emerged at the end of the

50s and in the beginning of the 60s, as a reaction against Socialist

Realism. This philosophy of art suggested that everything was

going along fine in society. All people were happy, contented

and working for the progress of the nation. "Severe Style"

mirrored reality more closely, showing the sadness, loneliness

and difficulties that individuals faced under the Soviet system.

Note:

The narrative, which follows below, is primarily the perspective

of Zarifa Salahova, except for the sections, which her brother

Tahir shared with us.Each speaker is designated. Note:

The narrative, which follows below, is primarily the perspective

of Zarifa Salahova, except for the sections, which her brother

Tahir shared with us.Each speaker is designated.

Zarifa: My father Teymur (1896-1938) used to work in the

Sabunchu oil fields. In fact, in 1906, he was involved in the

famous oil workers' strike in Balakhani, one of the most productive

petroleum regions on the Absheron peninsula at that time. Later,

Father joined the revolutionist activities. In 1919, he was admitted

to the Baku Communist Party.

As an experienced worker, they sent him off to study at a special

Communist Party school. After graduating, they assigned him to

work in Ganja at the Institute of Agriculture (now Academy).

Then he was sent to Dashkasan, close to the border with Armenia

where they were extracting ore for the aluminum plant in Ganja.

My father was the head of that border detachment.

In 1935

Father was assigned to help administer the town of Lachin near

southwestern Azerbaijan [now occupied by Armenia] in a post as

the highest Communist Party official there. Mir Jafar Baghirov,

who held the highest position in Soviet Azerbaijan as First Secretary

of the Communist Party and who served as Stalin's right hand

man, knew my father well. On several occasions, Baghirov had

been a guest in our home. He always praised my mother's food. In 1935

Father was assigned to help administer the town of Lachin near

southwestern Azerbaijan [now occupied by Armenia] in a post as

the highest Communist Party official there. Mir Jafar Baghirov,

who held the highest position in Soviet Azerbaijan as First Secretary

of the Communist Party and who served as Stalin's right hand

man, knew my father well. On several occasions, Baghirov had

been a guest in our home. He always praised my mother's food.

We used to live on the fourth floor of an apartment in the center

of Baku. We had only two rooms, a total of 36 m2 for the seven

of us - mom, dad and us five kids.

Our house had originally belonged to an Iranian merchant. After

the Bolsheviks established their power in Baku, the Iranian family

fled in 1922 and their house was split up into small apartments

for several families.

In 1925, my father was given two rooms on the fourth floor. We

had no bathroom, no kitchen. We had to share those facilities

with people who lived on the third floor. Later we built a very

small kitchen on the other side of the house, on what was the

roof. In 1956, my brother Sabir added a bathroom.

The Arrest

Tahir: They arrested Father on September 29, 1937. There

were five of us children. The eldest brother Sabir (1926-2001)

was 11 years old, Mahir (1927-1967) was 10 years old, I (1928-)

was nine years old, Zarifa (1933-) was five and our little sister

Leyla (1937-) was an infant of two months old. Father was 39

years old; mother was 36. My father's name was Teymur Heydar

oghlu (1896-1938), Mother was Sona Daryah gizi (1901-1984). She

was a housewife.

It was ten o'clock in the evening, September 29, 1937, when they

arrested my father. I had just started school that year because

I had been ill with scarlet fever the previous year. I remember

lying in bed beside Father. He was reading the newspaper. Somebody

knocked at the door. Father was wearing his white nightshirt,

pants and slippers. So he got up and let those people in.

Zarifa: Four people were there - two from the NKVD - Narodniy

Komitet Vnutrennikh Del (People's Committee on Internal Affairs

which became the forerunner of the KGB) and two of our neighbors,

one by the name of Sultanov and the other, an Armenian called

Gabrilyan.

Tahir: They told Father that he should come with them.

He told them that he needed to change his clothes. Mother walked

in at that moment and asked: "Have you done anything?"

Dad replied: "I've always been honest to the government

as well as to you."

Left: Zarifa Salahova in the mid-1930s. Her father Teymur

(top thumb photo) was repressed when she was five years old.

Zarifa's mother was left to take care of five children by herself.

Photo: Courtesy of Salahov family. Left: Zarifa Salahova in the mid-1930s. Her father Teymur

(top thumb photo) was repressed when she was five years old.

Zarifa's mother was left to take care of five children by herself.

Photo: Courtesy of Salahov family.

As it was September,

it was still hot outside. The two agents left the room and told

my father that they were going downstairs and would be waiting

for him there." Somehow, they had great respect for my father.

They trusted him.

Mom started to cry. Father kissed me. He asked mom where the

money was and she replied: "Why are you asking? You know

where the money is." And then he took some rubles and left.

I looked out of the window and watched them leave - my father

between those two NKVD agents. And that's the way it ended. For

months, I used to look out of the window wondering when my father

would be coming home again.

Zarifa: Actually Father had a hunch that they

might come after him. At the end of 1936, Mir Jafar Baghirov

had fired him from Lachin, accusing him of being a member of

a counter - revolutionary group who was trying to overthrow the

government.

Father denied any such involvement but it didn't matter. He lost

his job anyway and had to return to Baku. They also took away

his Communist party card.

At that time, Baghirov was living in the building opposite the

Philharmonic Hall on Istiglaliyyat Street - the building on the

corner [now opposite the President's Aparat]. Since Father had

no work, he decided to wait for Baghirov one morning and speak

to him about the situation. It was then that Father threatened

Baghirov: "Don't you know how loyal a Communist I am? If

you don't give me back my Party membership card, I'll kill you."

So there was a history to his arrest.

Baghirov knew my father well. Our summerhouse was in the suburb

of Buzovna outside of Baku near the sea; Baghirov's was in Zagulba

nearby. Sometimes on Sundays my father used to take us over to

Baghirov's place where we would have tea together, and my brothers

played with his children. I'm just trying to show you that Baghirov

knew our family very well.

Mom

didn't get to attend his trial. Nobody did. They sentenced father

to 10 years imprisonment, with the further restriction that he

would not be allowed to write any letters back to his family. Mom

didn't get to attend his trial. Nobody did. They sentenced father

to 10 years imprisonment, with the further restriction that he

would not be allowed to write any letters back to his family.

Above: The Salahov brothers who all became

artists: Sabir (1926-2001), Tahir (born 1928), and Mahir (1927-1967).

Early 1930s. Photos: Courtesy of Salahov family.

And so we waited and

waited. Little did we know at that time, that such a restriction

was shorthand for immediate execution.

When Father was in prison, Mom used to organize parcels for him.

They wouldn't allow food, so she would gather clothes and things

like that.

The last time Mom went to give a parcel for father was on July

3, 1938. She included six handkerchiefs in her pack. Father sent

back three of them with our names written on them. We didn't

understand at the time, but maybe he wanted to pass us a message

regarding the number "three". But how could Mom know.

Years later we understood that he was shot on July 3.

In the morning of that day, Mom passed the parcel for father

but it turns out that he was shot that same evening. We didn't

learn about it until 18 years later.

Waiting, Waiting

Zarifa: In 1947, I wrote a letter to Stalin

saying that Father had been sentenced to 10 years in prison and

soon those 10 years would be up. We wanted to know if Father

was alive or not. On August 18th, I was called to the October

Branch of the NKVD (now in the Yasamal region). They asked me

when my father had been arrested. At that time, we thought that

Father would soon return home in a month or so. But we heard

nothing further about Father until 1955.

All those years after father's arrest, we were left all alone

because our family had been isolated and charged with being a

family of the "Enemy of the People". Nobody came to

visit us those 20 years. Everybody was so afraid to have any

association with us.

Tahir: Even relatives. Actually, there weren't very many

relatives left. Already several of the relatives on Father's

side had been exiled somewhere. And nobody visited us from Mother's

side either, only her brother Haji. He was her younger brother

and the director of Baku's Botanical Gardens. In the 1930s, he

was the first person ever to receive the Academic title of Candidacy

of Botanical Sciences. Few people know about it today that he

was the first to plant pine trees and olive trees in Baku. He

was experimenting to learn which kinds of trees could flourish

in Baku.

What Mother did in taking care of us five children entirely on

her own, was really nothing short of heroic. We were so afraid

that she, too, would be exiled to Central Asia - as was the usual

practice of what they did with families when the father was arrested.

Mother was so worried that all of us children would be taken

to the orphanage so a decision was made how the children would

be divided up among the relatives - who would take care of each

one of us after Mother was sent away. Those years 1941-1945 -

the war years - were so difficult. Though the war was not fought

on Azerbaijan's territory, it still impacted us all. Everybody

was trying just to stay alive. Just to survive. Those were days

of famine. They would distribute ration cards for bread, sugar,

flour and other items.

Zarifa:

Mother had such a difficult time. Haji spent 500 rubles trying

to get a telegram through to Stalin, Voroshilov, Kalinin, Budyonov

- anybody - begging them not to exile my poor mother with her

five children to Kazakhstan. We really thought that they would

soon come to send us to all away to exile. Zarifa:

Mother had such a difficult time. Haji spent 500 rubles trying

to get a telegram through to Stalin, Voroshilov, Kalinin, Budyonov

- anybody - begging them not to exile my poor mother with her

five children to Kazakhstan. We really thought that they would

soon come to send us to all away to exile.

Left: Tahir Salahov (left) with eldest brother

Sabir. About 1930.

And then one day a car came and took Mother away. They took her

to the NKVD. There she was shown a document that came from Moscow

stating that, the family and apartment of the Salahovs were at

the disposal of Moscow.

Since Mother was uneducated, she didn't understand where the

order had come from. Was it from Stalin or somebody else? All

she knew was that it came from Moscow. The NKVD kept Mother from

12:00 noon and brought her back at 3 a.m. in the morning. Lucky,

for all of us! In the end, Mother was not sent away into exile.

Tahir: As children of an "Enemy of the People",

people used to stay away from us - avoid us. Nobody would play

with us at school or in the neighborhood; nobody would befriend

us. And so we started developing friendships with other kids

whose fathers also had been arrested. There were two or three

other children in my class whose fathers were gone: Toghrul Narimanbeyov's

father had been arrested and Victor Galyavkin's father was at

war. They both became artists and we all grew up together as

friends.

Zarifa: Since Mother was not educated, she had to take

on menial work. So she took on a job with the publishing house

Azernashr as a cloakroom attendant. Work started at 7 a.m. She

used to take in about 500 hundred coats in the morning. Then

she would sew covers for chairs in the afternoon. At 5 p.m.,

she would go back to the cloakroom and return the coats to their

owners, and then at nights, she would wash clothes.

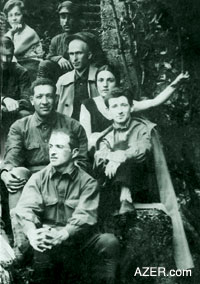

Left: The only photo that the Salahov Family has of

their father Teymur (second row, left) except for one with his

brothers. He was arrested and executed shortly afterwards because

of a quarrel with the top Communist leader in Azerbaijan Mir

Jafar Baghirov. His wife Sona raised the five children on her

own. To her crerdit, they all became professionals in their field.

Photo: Courtesy of Salahov family. Left: The only photo that the Salahov Family has of

their father Teymur (second row, left) except for one with his

brothers. He was arrested and executed shortly afterwards because

of a quarrel with the top Communist leader in Azerbaijan Mir

Jafar Baghirov. His wife Sona raised the five children on her

own. To her crerdit, they all became professionals in their field.

Photo: Courtesy of Salahov family.

Two or three years of

our childhood were spent there. We would go there after school.

Then, in 1941 the war began. There was a woman by the name Tyotya

Shura (Auntie Shura) working in human resources of Azernashr

Publishing House.

Mom used to go to buy "piroshki" [a pastry with meat]

for the workers. And that lady showed sympathy for her and would

write down an extra piroshki on the order so that Mother could

give it to us - her children. These piroshkis had a little meat

in them and Tahir used to take it and make soup for us.

There was a deputy director of Azernashr by the name Akhundov.

One day he called Mother and told her to take an extra 10 piroshksi

for him. Mom told him that she couldn't do that because she had

to order a specific number of them and that she couldn't take

any extra one. When Mother didn't say "yes" to this,

Akhundov transferred her to a military factory in the Razin district.

That was 1942. There she worked at foundry shop, which started

work at 5 a.m. Mother would return home at 1 p.m.

With Mother working so much, we didn't get to see much of her.

At the factory, she had to lift heavy artillery and got a hernia.

So they sent her to the hospital for an operation. Afterwards,

they dismissed her from the factory and wouldn't let her work

there anymore.

There used to be one-story building

opposite the building where the Turkish Airlines is now located

[Husi Hajiyev Street]. It housed a tailor shop for children,

operated by Golda Salomonova, a Jewish woman. She hired Mother

at her shop, knowing that she had five children. She used to

let Mother take the orders home to sew so that she could take

care of us at the same time. Another Jewish woman, Maria Lvovna,

taught Mom how to make pants so Mom started sewing trousers for

the friends of my brothers for 30 rubles. She used to sew three

pairs each day. Then Golda would register only two of the orders

that she made. In that way, Golda helped Mother so much. It enabled

her to keep the money from the sales from that one pair of pants

and that's what we used to live on.

|

"I looked out

of the window and watched them leave - my father, between those

two agents. And that's the way it ended. For months, I used to

look out of the window wondering when he would come back home

again. He never did."

--Tahir Salahov,

artist, who was nine years old when his father was arrested in

1938.

His family didn't learn that their father had been shot until

1956 - 18 years later.

|

Where's My Father? Where's My Father?

Zarifa: In February 1955, I was returning back

from the city of Oryol to Baku on the Moscow-Baku train. I was

a member of the women's national basketball team. I was the only

Azerbaijani on the team. The other team members were Armenians

and Russians.

Left: Tahir Salahov's mother, Sona, brought

this Century plant from Crimea 30 years earlier and planted it

int their garden at their summer house. Finally after 25-30 years,

it suddenly started to blossom. The plant is now about seven

meters tall. To Tahir, it is symbolic of the endurance of his

mother's character. She raised five children - all by herself

- after her husband was arrested and executed.

While on the train, I heard people say that Guskov, Chairman

of the KGB for Azerbaijan, was riding on the same train with

us. But he was in an international compartment, which could be

recognized by its dark burgundy color. It was different from

the other train compartments. I knew that the train would be

making a 30-minute stop in the city of Khorkov and so I tried

to see if I could meet with him.

The conductor told me that Guskov was resting and told me to

meet him when the train stopped in Rostov. So when we arrived

there, I went to Guskov's compartment and knocked on the door.

He opened

it. He invited me to come in. It was a big thing for them to

allow a young student like me into the compartment of the head

of the KGB. There was a sofa in that dark wine-colored fabric.

And his wife was seated looking out the window. He gestured for

me to sit down. I so desperately wanted to ask him about my father.

We had not heard any news about him for years. He opened

it. He invited me to come in. It was a big thing for them to

allow a young student like me into the compartment of the head

of the KGB. There was a sofa in that dark wine-colored fabric.

And his wife was seated looking out the window. He gestured for

me to sit down. I so desperately wanted to ask him about my father.

We had not heard any news about him for years.

Guskov asked me all kinds of questions - like where I came from,

about myself, my brothers and my mother. He also asked what my

mother was thinking about in terms of what had happened to my

father. I told him that she believed, that he should be alive

because he was a very strong man if they had not killed him.

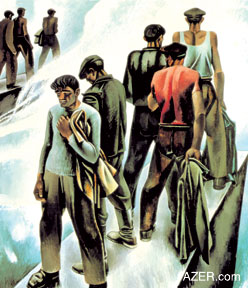

Left:

Forbidden: No Entrance.

Artist Tahir Salahov was nine years old when Stalin executed

his father. Work entitled "Prague Alleyway". 1960.

Photo: Art by Tahir Salahov.

That was a Monday when I met Guskov. He then invited me to stop

by his office on Wednesday. When I arrived on Wednesday, I was

told that the appointment list was already full and that he would

not receive anyone else. But I persisted, telling them that Guskov

himself had told me to come to meet with him.

After they learned my last name, they called me upstairs and

I did get to meet with Guskov. He again asked me what Mother

thought about the situation. And I again told him that she thought

he should still be alive if they had not shot him.

Guskov told me to write a letter and request that my father's

case be reviewed. So I wrote a letter on behalf of my mother

and gave it to him. He asked if our apartment and our belongings

had been confiscated or not. I told him that there had been an

order from Moscow, that's why they had not moved us out of the

apartment.

I left the letter with Guskov. A week later, they called again

for me to meet him. It seems he already had reviewed father's

case, but again he asked me what Mother thought. And again, I

repeated what I had told him before.

The following Wednesday, they called me for yet a third time.

There was a large reception hall there and several people were

sitting there. By that time [1953 after Stalin's death in March]

Mir Jafar Baghirov had already been arrested. Those people sitting

there had been called to be witnesses against him. They also

called some prisoners who had been arrested and then freed after

many years.

|

"Nobody nobody

- not until 1956 when my father was rehabilitated - nobody ever

came knocking on our door to see how Teymur's children were doing.

Or whether they were even alive or not. Simply, they were afraid."

-- Zarifa Salahova,

whose father was arrested and killed when she was five years

old.

She was the second youngest of five children in her family, ages

11 years to 2 months.

|

There was also an old man with

gray hair in the room. He asked me: "Are you Teymur's daughter?"

He stood up and kissed me, and asked, "How is Sona doing?"

He also asked how my brothers were. It seems he knew all of us

by name. The only one he didn't know was my youngest sister.

It turned out that he had spent 18 years in prison and then been

rehabilitated and now was being called upon as a witness at Baghirov's

trial.

He asked me why I was there? I told him the whole story and then

he asked me: "When was the last time that you sent a parcel

to your father?" I replied, "On July 3, 1938."

He told me that signified that Father had been shot on the same

day. I started to cry. After a while, I was asked to enter Guskov's

office. He saw me crying and asked me what happened. I told him

that someone in the waiting area had told me that Father had

been shot 18 years ago on the exact day that we had sent the

last parcel on July 3, 1938.

Guskov told me: "You see, it's not our fault, but still

we have the responsibility to pass on such bad news as this."

It means that even though I had met with him in his office on

three separate occasions, he had known all along that Father

was dead, and yet he had not told me anything.

Guskov tried to console me by saying that they had not exiled

our family after Father had been arrested. And that all of the

children in our family had been able to pursue their studies.

He added that he would pass my letter to the Military Tribunal

near Old Intourist Hotel here in Baku. Three members of that

tribunal had come from Moscow and set up their office there.

They were the ones reviewing the cases. Guskov asked me to go

there once a month to determine what the results would be.

After that, I used to go to Military Tribunal once a month to

hear if there was any news related to my father's case. About

a year later in February 1956, I met Colonel Chesnyakov, who

told me, "We've finished reviewing the case of someone called

Salahov. What was your father's name?" I said: "Teymur

Heydar oghlu". And he told me: "He was found 'not guilty'

of any criminal activity." But it had taken them a year

to review the case-from February 1955 till February 1956.

I was in my fourth year at the institute and very glad to hear

the news. I kissed the Colonel and the people sitting near him.

They told me that they would send my father's case to the Supreme

Court, which would send us an official document declaring that

my father's innocence so that his name could be cleared. Five

months later, on July 14, 1956, according to the decree of USSR

Supreme Court, Father was officially rehabilitated.

Enemy of the People Enemy of the People

Zarifa: Father's arrest had affected us in such a negative way

as we were treated as "Children of the Enemy of the People".

Let me give you some examples. In 1950, when my brother Tahir

was applying to the Art Academy in Leningrad (now Petersburg),

he noted there that his father had been arrested in 1937. Even

though Tahir had received excellent marks on all his exams, the

simple mention of our father's arrest prevented Tahir from being

admitted into the Academy.

Left:

"Morning in Moscow",

1959. Photo: Art by Tahir Salahov.

But the rector was nice, he sensed that Tahir was talented and

told him not to leave Leningrad. He then organized to send Tahir

to the Technical School of Industrial Art to study for one year,

saying that it would be useful for him. Tahir went. But since

he didn't have warm clothes, he caught cold and ended up in the

hospital.

The doctor at the hospital was very kind to him and even brought

food from his home for Tahir. He advised Tahir to leave Leningrad

because he feared if he stayed, he would contract tuberculosis.

So Tahir returned to Baku that summer and applied to the Surikov

Art Institute in Moscow. This time, on the application form,

he didn't write that father had been arrested. He mentioned that

his father had been a worker in the oil fields and had been killed

by an electrical shock. And thus, Tahir was admitted to Surikov

Institute.

In 1952, I graduated from the Sabir Pedagogical Technical School.

In March, a commission was held to assign locations where the

graduates would teach throughout the country.

Sona Aslanova used to work as Deputy Minister of Education, but

at the time of Father's arrest, she had been working with Mir

Jafar Baghirov at the Central Committee and had known my father

well.

She was head of the propaganda department. When my turn came,

they introduced me as "Zarifa Salahova, activist. Speaks

Russian fluently. Plays on the national basketball team,"

and such things. In other words, they were praising me.

Sona Aslanova asked, "What's your father's name?"

"Teymur", I replied.

"What's his father's name?" she asked.

"Heydar," I replied.

The three members of the tribunal all knew that father had been

arrested in 1937 and that we didn't know what had happened to

him.

Sona Aslanova continued asking, "Where is your father?"

I told her that he used to work in the oil fields and had been

electrocuted. She commented: "Maybe he died in prison?"

I told her I didn't know since I was little when it happened

and that's what my mom had told me. As I was one of the leading

students, I had all "excellent" marks with the exception

of a few marks-"good". It meant that I could continue

my education and enter the Institute. But, instead, Aslanova

told them to send me to Yardimli school near Iran to teach Russian.

Can you imagine? I was supposed to go to Yardimli and teach Russian

there in 1952? Yardimli was a very backwards place at that time.

When she said "Yardimli", Rafiga Akhundova, a member

of the Committee put her finger to her lips gesturing for me

not to say anything. But you see, as a child of an "Enemy

of the People", we had to deal with all these kinds of injustices.

But in the end, they didn't send me to Yardimli as I was in the

list of outstanding students. And so, instead, I did get to continue

my education at the Institute.

Rehabilitation

Papers

After the papers came that Father had been rehabilitated, Mom

was given a pension of 150 rubles as the head of a family since

her husband had been killed. She continued to receive this pension

until she died. In addition, they used to pay all household utilities

such as electricity, gas, and telephone. Also, Mother was given

free medical treatment at health sanatoriums.

Mother had to wait and wait so many years to learn what had happened

to Father. And they had called me three times to meet with Guskov.

Never once did they tell me that Father was dead, but maybe from

such an absence and lack of information, Mother had figured it

out. And then that third time, when I came home crying, I think

Mom understood everything.

I was the one who had to break the news to my mother. Me - a

girl. It wasn't my older brothers. After all, I had been the

one who had written the letter to Stalin as a youth. My brothers

had been afraid to write such a letter. They were afraid that

the authorities would come and arrest them as well. And I had

been the one who approached Guskov.

|

|

Above: Now 70 years after the arrest and

execution of his father Teymur Salahov, artist Tahir Salahov

is finally preparinig the sketches to paint his father's portrait

from prison photos found in the KGB files. Top Corner: Tahir

Salahov in his studio with sketches of his father. August 2005.

Photos: Art by Tahir Salahov.

You know, nobody helped us during those difficult times. Everything

that we achieved, we achieved with our own hard work. Everybody

cut off their relationships with us. Only my uncle (my mother's

brother) helped us. He sent a telegram to Moscow, pleading with

them not to exile our family to Siberia. Nobody, until 1956,

when my father was rehabilitated ever came knocking on our door

to see how Teymur's children were doing. Or whether they were

even alive or not. Simply, they were afraid.

If I had not met with Guskov on the train. For certain, we would

not have dared try to approach him because we were too frightened.

|

"Mom didn't get

to attend Father's trial. Nobody did. They sentenced him to 10

years imprisonment, but they didn't allow him to write even a

single letter back to his family. And so we waited and waited

and waited [18 years]."

-- Zarifa Salahova

[whose family didn't realize that

a sentence that prohibited correspondencesignified that

the victim was to be shot immediately].

|

When Tahir was studying in Moscow,

he would come to Baku on his summer vacation. Other artists,

who were members of the Artists' Union, could take orders and

earn money painting. But Tahir couldn't, as he was not a member

of the Union. He used to paint works for other artists, and they

would give him half of their commission. That's how he earned

money. And he used to give half of this money to us and keep

the rest for himself. My other brothers also worked, but they

had jobs at the cinema and the tram park and didn't earn as much

money.

When I was studying at the institute, someone introduced me to

a Russian woman who was a tailor who lived in our neighborhood.

I had good embroidery skills and cashmere was the rage at that

time. This woman used to make clothes for the wives of ministers.

I would embroider the large decorative collars for the dresses,

and she would give me 80, 100, 120 rubles for each piece.

On several occasions when I went to the opera, I would see women

wearing the collars that I had embroidered. Back in those days,

there weren't many ready-made clothes; everything was made by

hand. These women didn't know that I had done the embroidery

on their clothes.

One day I told Mom: "Why do I need to study, I can earn

money doing embroidery?" Her rebuttal was sharp and immediate:

"If you want to spend the rest of your life like me with

a needle, then go right ahead and drop out of school."

When I was admitted to the Komsomol, I strutted home so proud

to show off my membership card. But my second brother Mahir grabbed

the card and threw it down and stomped on it. I had faith in

Stalin back then. I wasn't aware of so many things at that time.

Can you believe? I didn't understand that there was any relationship

between Stalin and with what had happened to my father.

It wasn't until 1956 when I was in my fourth year at the institute

and Khrushchev sent an Open Letter to the 20th Congress condemning

the "personality cult" that had grown up around Stalin

that I began to understand who this man was. Khrushchev's speech

was very long and we had to read it in turns.

When

my turn came, after reading for half an hour, I stopped and left.

After we had suffered so much, I didn't see any purpose in criticizing

Stalin. When

my turn came, after reading for half an hour, I stopped and left.

After we had suffered so much, I didn't see any purpose in criticizing

Stalin.

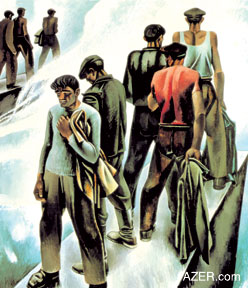

Left:

Tahir Salahov was one of

the co-founders of the Soviet trend in art called "Severe

Style" of the 1950s and 1960s. In contrast with Socialist

Realism, it shows people isolated and lonely in their everyday

life struggles. Note here that all the figures are looking in

different directions. Work is called "New Sea", 1970.

Photo: Art by Tarhi Salahov.

It was Mir Jafar Baghirov who had sent the list of tens of thousands

of people from Azerbaijan to Moscow. In 1986, I found the telephone

number of Guskov when I was in Moscow. I called him up and asked

if I could stop to see him. He agreed. So I took a journalist

with me. I bought a bouquet of flowers and some chocolates and

went to his home. I reminded him of the story of how I had met

him on the train. Of course, he didn't remember me, as he had

met so many people like me who were inquiring about the fate

of their loved ones. But he admitted that he had always been

very nervous and upset when he had to break the news to anyone

that their dear ones had been shot to death.

We really don't have any photos of our father. Historian Ziya

Bunyadov made a negative of this photo of father from the archive.

[Shows a prison mug shot - front view and side view]. It was

a glass negative. Except for the prison photos, we have only

one photo of Father and there's one separate picture of his brothers

all together.

And there's a photo of me by myself when I was five years old.

My younger sister has no photo of herself at all when she was

small. Our family didn't have a camera back then. The memories

I have of my father are hazy. Keep in mind, I was only five years

old when he was arrested and we never saw him again. But I remember

him as a very tall person and very strong.

Once when Tahir and I were lying in bed, sick with scarlet fever,

dad came home at night, bringing two yellow melons for my brother

and me. After we got better, Father took us to the candy shop

that was on the first floor of the building where the Literature

Museum [Metropol Hotel at the time] is now located. He told us

that we could order whatever we want. And as we had been on a

restricted diet for a long time, I remember we ordered almost

everything - as if we had never eaten sweets in our lives before.

I always remember this when I think of Father. I know he loved

us children very much.

Ulviyya Mammadova assisted Betty Blair in interviewing and translating

materials for this article.

Back to Index AI 13.4 (Winter

2005)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|