|

Autumn 2006 (14.3)

Pages

26-35

Hafiz Pashayev

Reminisces

Azerbaijan's

First Ambassador to the United States

1. Section

907 of the Freedom Support Act: What is it?

2. Ambassador

Hafiz Pashayev:

Other Articles Published in Azerbaijan International

The

Soviet Union had just collapsed (late 1991). Everything was in

chaos. The enormous network between 15 republics that had been

operating for more than 70 years had been abruptly severed breaking

the links shared between spheres such as medicine, science, education,

social services, manufacturing and the arts. The

Soviet Union had just collapsed (late 1991). Everything was in

chaos. The enormous network between 15 republics that had been

operating for more than 70 years had been abruptly severed breaking

the links shared between spheres such as medicine, science, education,

social services, manufacturing and the arts.

Add to the confusion and economical turmoil of those days, the

disastrous war with Armenia over the territory inside Azerbaijan

known as Nagorno Karabakh which had left Azerbaijan overwhelmed

with hundreds of thousands of refugees desperately seeking adequate

shelter, food, water and safety, not to mention the drastic urgency

to attend to medical and psychological needs of those displaced

citizens who had been forced at gunpoint to abandon their communities,

their property, which meant leaving behind much of their identity,

their networks, and even their loved one's graves.

And though the United States had pledged to assist the former

Soviet republics with substantial financial aid until they could

find their way and get back on their feet, there was a small

clause - which became known as Section 907 of the Freedom Support

Act that prohibited any aid - even humanitarian in nature - to

be given directly to the Azerbaijani government.

Armenians had succeeded in getting Congressional representatives

to inject this restriction into the legislature despite the fact

that it was information based on lies and misrepresentations.The

circumstances were far from ideal in an attempt to begin building

cordial relationships with representatives of the one remaining

super power in the world - the U.S. That responsibility was thrust

on Hafiz Pashayev, Azerbaijan's first Ambassador to Washington.

Interestingly, we announced Pashayev's appointment in that first

issue of Azerbaijan International, which we published in January

1993. Now 14 years later, the Ambassador's assignment is over

and he has returned to Baku. He kindly agreed to sit down with

us again and share some of his insights and reflections about

his years in Washington. Azerbaijan International's publisher

Pirouz Khanlou interviewed the Ambassador in Baku on August 26,

2006.

______

Azerbaijan International: In your new book - Racing Up Hill

- you describe those first years serving as Azerbaijan's first

Ambassador to the United States like being asked to climb Mt.

Everest with little knowledge of the idiosyncrasies of this giant

peak. You were referring, of course, to obstacles hindering the

Azerbaijani-U.S. relationship because of the passage of Section

907 of the U.S. "Freedom Support Act"1 which

denied all direct aid to the Azerbaijani government. Azerbaijan International: In your new book - Racing Up Hill

- you describe those first years serving as Azerbaijan's first

Ambassador to the United States like being asked to climb Mt.

Everest with little knowledge of the idiosyncrasies of this giant

peak. You were referring, of course, to obstacles hindering the

Azerbaijani-U.S. relationship because of the passage of Section

907 of the U.S. "Freedom Support Act"1 which

denied all direct aid to the Azerbaijani government.

Here we are - nearly a decade and a half later - and that piece

of U.S. Congressional legislation is still effectively on the

books. Of course, some might argue that it doesn't really matter

these days as Azerbaijan has found its own way without aid from

the U.S.

Others might point out that despite the law, Azerbaijan is currently

receiving assistance because each year since 2002, President

George W. Bush has personally signed a waiver allowing some aid

to be channeled to Azerbaijan's government, though most of the

funds are earmarked for projects related to security in support

of America's alleged "War on Terror". But given how

history has played out, from your perspective what difference

would it have made if there had not been that restrictive clause

back in 1992?

What difference would it have made if the U.S. had directed aid

to the Azerbaijani government as it did to each of the 14 other

former republic 2 of the collapsed Soviet Union?

Ambassador

Pashayev:

It would take an entire

day to exhaust this subject. For sure, Section 907 had many implications

for Azerbaijan and for those early bilateral relations between

our two countries. Many of the pages in "Racing Up Hill"

deal precisely with this issue.

Left: Ambassador Pashayev congratulating U.S. President

Bill Clinton in the Capitol Building on the occasion of his State

of the Union Address, January 1999. Left: Ambassador Pashayev congratulating U.S. President

Bill Clinton in the Capitol Building on the occasion of his State

of the Union Address, January 1999.

But it wasn't only the refugee

situation that overwhelmed us. Everything was in chaos. The enormous

network between the 15 republics of the former Soviet Union,

which had been operating for nearly 70 years, had totally collapsed,

abruptly severing the infrastructure of the vastest nation in

the world which stretched across 12 time zones. All links in

the spheres of economic, medical, educational and social services

had been cut. We, along with the other republics, felt that we

had been abandoned and orphaned.

For the reason, the U.S. government's

decision to deprive us of assistance during the desperateness

of our fundamental needs, was a devastating blow to us morally.

One must view Section 907 in its historical and political context.

Throughout those long years of the Soviet occupation of our country,

we had looked to America as a beacon of hope, democracy and justice.

For us, America could be counted upon to be a strong defender

of human rights. We had aspired to those life-affirming qualities;

we dreamed of the day when government would look after our own

people in the same way.

First of all, it's true that we did feel the economic impact

of not receiving humanitarian assistance in those early days

of our independence. The tragic conflict with Armenia over our

territory in Nagorno Karabakh (NK) had left us with more than

700,000 refugees. We desperately needed to improvise basic shelter,

and provide food, water, and exposure from severe climactic conditions.

The mere survival of our people depended upon it. In addition,

there were enormous medical and psychological needs of our displaced

population who had been forced to flee their property, their

communities and, virtually, everything they knew.

So the first close political encounter with the U.S. that we

had as an independent fledgling country shocked us very deeply

in the core of our psyches. Finally, as we were trying to shake

off Soviet oppression - an effort which the United States themselves

had actively endorsed and encouraged - we discovered that they,

too, had shunned us, ignored our needs and abandoned us when

we needed help the most. Psychologically, it was a demoralizing

blow.

How could America deny aid to us in those needy days when they

were pouring billions - not just millions - but billions - of

dollars into the infrastructure of the other former republics

of the Soviet Union? And how could they deny aid to us - the

victim of aggression - when they were showering significant aid

on the Armenians who had brought all this devastation and death

upon us? To this day, our people do not understand this.

Left: Hafiz Pashayev and wife Rana with Brent Scocroft

at the Farewell Reception for Ambassador Pashayev, July 2006.

Air Force General Snowcroft served as National Security Advisor

under President George H. W. Bush (current Bush's father) Left: Hafiz Pashayev and wife Rana with Brent Scocroft

at the Farewell Reception for Ambassador Pashayev, July 2006.

Air Force General Snowcroft served as National Security Advisor

under President George H. W. Bush (current Bush's father)

From the very first day of its passage on April 1, 1992, it was

obvious to us that this decision could not be justified. Let

me be fair and add that many Americans also understood how unwarranted

and wrong this judgment was. Armenia accused Azerbaijan of a

so-called "blockade against Armenia". It was a very

skillful Armenian subterfuge that served them well, especially

among uninformed Americans.

Even the United Nations had identified and condemned Armenia

as the aggressor in this war over Nagorno-Karabakh. Between 1993

and 1994, the UN had passed four resolutions condemning Armenia's

aggression on our territory. And yet, via the Freedom Support

Act, the United States was blaming and punishing us for the war.

There were times when I would visit Congressional office that

it seemed like I had to prove to everybody that I wasn't some

sort of nomadic creature from the desert, far removed from civilization

- that I was, in fact, a human being. That was the situation

we dealt with in Azerbaijan back in 1992-1993.

I'll never forget some of the discussions we had with members

of Congress and their staff. Of course, the substance of those

meetings primarily related to the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict

and Section 907. We would go back again and again to the same

office and hear the same diplomatic cordialities: "It's

nice to see you again, Mr. Ambassador." Or "We will

definitely try to address your concerns, Mr. Ambassador."

"Let me see what we can do to improve the humanitarian situation

in your country," and so on. In short, I got nowhere beyond

politeness.

That reminds me of another incident in the mid-1990s when Madaleine

Albright was Secretary of State under President Bill Clinton.

During a meeting with our Foreign Minister [Hasan Hasanov at

the time], she closed her remarks, attempting to compliment me

in front of my boss for the job I was doing in Washington. The

Minister looked at me and then turned back to her and commented:

"We'll make a judgment about his work in Washington after

Section 907 is repealed." Albright immediately responded:

"Poor Mr. Ambassador. He might have to stay in Washington

for the rest of his life." It seems she wasn't far off target.

Left: Colin Powell (center), as U.S. Secretary of State

during the first administration of President George W. Bush at

a reception hosted by Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld

(left) on September 10, 2004. Left: Colin Powell (center), as U.S. Secretary of State

during the first administration of President George W. Bush at

a reception hosted by Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld

(left) on September 10, 2004.

You remember all those difficulties that Azerbaijan went through

1992, 1993 and 1994.3 Other

former Soviet republics were receiving significant assistance.

During those years, approximately 13 or 14 billion dollars of

U.S. assistance was granted to countries that had finally won

their freedom shaking off the yoke of the Soviet Union. And the

Azerbaijan government was deprived of any of it.

AI: What impact did Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act have

on the Nagorno Karabakh conflict?

Ambassador Pashayev: The greatest consequence of 907, however,

was the enormous negative impact it had upon the peace process

and the resolution of the conflict between Armenia and my country

over Nagorno-Karabakh. Whether this is what the U.S. intended

or not, the legislation which denied us aid emboldened Armenians

and gave them an edge over us - an advantage in the conflict.

Section 907 was interpreted both by Armenians and Azerbaijanis

as indirect support for Armenia, especially in relationship to

the resolution of this war.

Clearly, Section 907 has had an enormous negative impact on the

region by slowing down the peace process. The Armenian Diaspora

and their lobbyists are still able to seize the advantage and

insist on a hard-line position rather than negotiating a peaceful

resolution. It emboldens Armenians to insist on independence

for Nagorno Karabakh or in joining the land that they captured

during the war to Armenia. But this is our territory.

Most people in the international community recognize that Armenia

is the aggressor and Azerbaijan is the victim. We are the ones

who had an enormous burden of refugees and lost about 15 percent

of our territory. Many Azerbaijanis do not view the U.S. as an

honest broker in the peace process. The American government is

not perceived as an impartial negotiator.

AI: What difference would it have made to the average Azerbaijani

if there had been no embargoes in those very critical days when

Azerbaijan was dealing with a war with Armenia and the displacement

of hundreds of thousands of refugees on its small, impoverished

territory?

Ambassador Pashayev: Even to this day, Azerbaijanis do not

accept that Section 907 is still in place. When I take taxis

in Baku, drivers often comment: "We're best friends with

the U.S. We're doing our best to strengthen our relationships

with them. We've made our energy resources available to them.

We're actively engaged in their 'War against Terror'4. We've even

sent our men to assist in Iraq. Ordinary people in Azerbaijan

simply cannot understand why the U.S. has placed these sanctions

against us. They are always asking, "Why, why, why?!"

A big part of my job has been to try to explain why it happened.

It's not because the U.S. isn't friendly towards us. It's the

reality of their political system, which allows lobbyists, even

minority ethnic groups, essentially to buy Congressional votes.

There's no valid reason why sanctions were imposed on Azerbaijan.

To tell you the truth, it's becoming more and more evident that

the political system in the United States needs a major overhaul

because of the overwhelming influence that small ethnic groups

or other lobbyists can have on Congress, influencing them with

monetary support, which, in turn, determines the outcome of elections.

I'm convinced that such factors are undermining U.S. foreign

policy, not only in relationship to Azerbaijan, but towards every

major issue in general. And this is extremely detrimental to

the institutions of democracy. It damages the democratic process.

The profound negative influence of lobbies on the U.S. government

has become a major topic of discussion in many political circles.

The two primary reasons why Armenians still expect to achieve

full independence of Nagorno Karabakh is that during the first

years of our independence, Armenia received support from Russia

as well as from the U.S.

|

Left:

The building

of Azerbaijan's Embassy in Washington D.C., was selected during

Pashayev's tenure.

AI: Did anything good come

from not receiving U.S. aid? Was it all negative?

Ambassador Pashayev:

You're right. Some good did come out of it. In fact, one should

not underestimate the benefits that resulted from having those

sanctions placed against us. First of all, we learned not to

depend on anyone except ourselves and not rely on major powers

to bail us out of our own complicated situations. Secondly, it

obliged us at the Embassy to become fast learners of the U.S.

political system. Section 907 became a major case study for Azeri

diplomats. Actually, those experiences served as an apprenticeship

for many of the outstanding young diplomats who now have taken

on very prominent positions in international relationships. For

example, Elmar Mammadyarov who worked with me in Washington is

now Azerbaijan's Minister of Foreign Affairs. Fakhraddin Gurbanov

is Ambassador to Canada, Elin Suleymanov has just opened the

Consulate in Los Angeles. Taghi Taghizade is the Press Secretary

for the Ministry now. |

Our embassy became a training ground for understanding the intricacies

of Washington. Colleagues in other embassies often sought our

advice when dealing with Congress.

AI: You've been conscious

of many dozens of meetings where top leaders have discussed and

attempted to negotiate a resolution of the war with Armenia,

how do you think the Nagorno-Karabakh problem can be resolved?

Ambassador Pashayev:The Caucasus states have a choice to

make because the outcome to this war is not historically inevitable.

We and our neighbors can continue to dwell on the animosities,

hatred and conflicts of the past; in which case, we will continue

the cycle of violence, death and poverty. Clearly, if we do not

solve these problems ourselves, others will attempt to solve

them for us at the expense of our own independence.

There's one historical principle in which I believe: those who

remain preoccupied with the past will lose their hope for the

future. Those who look backward can never see the future. Preoccupation

with the past and the issues of territorial expansion have led

to devastating results for the entire region.

AI: But the recalcitrance of Armenians in this conflict has

had its own repercussions. It has backfired. For example, the

most direct route for Baku's oil pipeline to the Turkish Mediterranean

was not through Georgia, but through Armenia. But when Armenia

was not willing to resolve the Nagorno-Karabakh problem, Azerbaijan

refused to allow the pipeline to go through their territory.

The pipeline detoured Armenia resulting in Georgia becoming the

beneficiary. As a consequence, the pipeline is really longer

than it needed to be and Armenia as a poverty-stricken, land-locked

nation, missed an enormous opportunity. Armenia would have made

millions of dollars in transit fees alone for the rights for

oil to pass through their country on its way to market.

Ambassador Pashayev: Armenians are missing many opportunities

available in the region. That's true. But it's the fault of their

Diaspora that continues to lobby the U.S. Congress and hold to

such a strict, hard-line position. Let me also mention that one

should not overlook how private business exploits the situation.

Every year, Armenians hold telethons to raise money on television

and they succeed in raising millions of dollars. It's a known

fact that many of those funds never reach Armenia. One must never

forget how the war can be exploited as a business opportunity.

In the long run, these selfish private interests complicate the

process of solving this conflict.

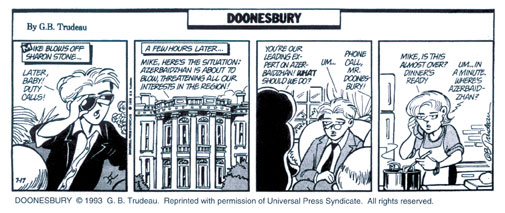

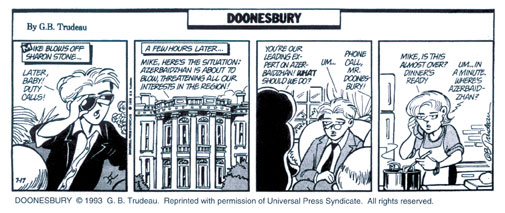

Left: Doonesbury comic strip by Garry Trudeau in early

1993, reflecting how little was known about Azerbaijan - even

in governmental circles. Left: Doonesbury comic strip by Garry Trudeau in early

1993, reflecting how little was known about Azerbaijan - even

in governmental circles.

AI: As Ambassador those first

years in Washington, what were some of the perceptions people

had about Azerbaijan. After all, as a newly independent country,

Azerbaijan had been relatively obscure and unknown for 70 years.

I remember how often we used to meet people who hadn't a clue

even how to pronounce the name "Azerbaijan" correctly.

Ambassador Pashayev: Americans

had such little knowledge about Azerbaijan during those early

days. Most people didn't know anything at all about our country.

Often people would call us seeking visas to visit Abidjan [Ivory

Coast] or Abuja [Nigeria]. People would ask: "Are there

any McDonalds in your African nation?"

Or there was a cartoon published in 1993 by political satirist

Garry Trudeau. In the four-cell scenario, he sketches the boss

in the White House calling on the so-called "leading expert"

of Azerbaijan to get his advice. "Azerbaijan is about to

blow", he is told. At the same moment the "expert"

receives a phone call from his wife, wondering when he will be

arriving home for dinner. Totally befuddled, he uses the opportunity

to ask her: "Do you know where Azerbaijan is?"

Americans are quick to admit that they don't know geography very

well. I remember during my first visit to California in 1975

where I spent 10 months in graduate studies in physics, I was

once stopped by a policeman. He looked at my driver's license,

which had the name and emblem of the Union of Soviet Socialist

Republics (USSR) and asked: "Where's that?"

I deliberately didn't mention Russian and named some other places

such as Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Moscow, Kyiv, Leningrad, Baku. Only

after I mentioned the word "Russia" did he look at

me and say: "Yes, I know where Russia is, but you don't

look Russian to me." This lack of awareness about our part

of the world meant that a great part of my mission in Washington

was simply to educate Americans about Azerbaijan, beginning with

very basic information.

I'll never forget another incident when a member of Congress

was surprised to learn that Armenia was not surrounded on all

sides by Azerbaijan. "I would never have voted for the U.S.

sanctions against Azerbaijan if I had realized that at the time,"

he confided.

|

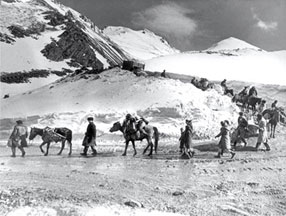

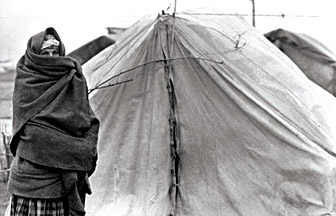

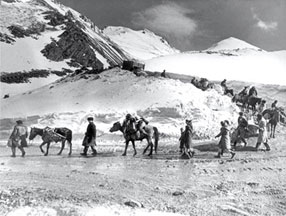

Left: The realities of Nagorno-Karabakh war

with Armenia. Fleeing Kalbajar in the mountains of the Caucasus.

Photo: April 1993.

AI: What is the difference

between the way that Azerbaijanis perceive the United States

today as compared with 10 years ago?

Ambassador Pashayev: In the 1990s, when relations between

Baku and Washington were gradually strengthening, I also observed

the transformation of both American and Azerbaijani societies.

While Monica Lewinsky5 was becoming

a household name in America, the people of Azerbaijan were awakening

to the world around them, including life in America. We were

both puzzled and amused by the whole Clinton affair. But in the

end it offered, not just a window into the complex life of politics

in America, it also pointed to the strength of the American political

system. It meant that one could, indeed, question authority without

resorting to violence and mayhem. The lesson learned was that

the President of the most powerful country on earth could be

held accountable. Not surprisingly, good governance, democracy

and human rights started to creep into the lexicon of Azerbaijan's

political culture.

|

|

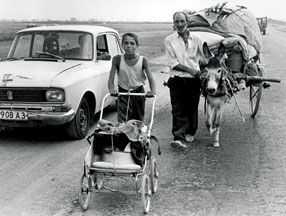

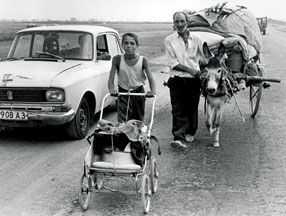

Left:

Azerbaijanis used whatever mode

of transportation was available to flee from the attacking Armenians

- helicopters, trucks, tractors, cars, horses and donkeys. Many

of them had to walk on foot dozens of kilometers before reaching

safety. Photo: 1993.

Despite this, it's difficult

for me to explain to our public that the U.S. genuinely wants

democracy to develop in Azerbaijan. Many people here view democracy

as another guise that the U.S. uses to impose its own influence

or presence here in Azerbaijan. People sometimes ask me if the

U.S. genuinely advocates for human rights. They say that if it

were really true, at least, the U.S should talk about, think

about and help our refugees and that they should be an honest

broker when it comes to Armenian aggression towards Azerbaijan.

These are the issues that people are raising here. When some

members of Congress come here preaching about human rights, Azeris

immediately point out that the U.S. themselves hindered human

rights when it came to our refugees.

Of course, the U.S. has one

of the most-developed democracies in the world. Its political

system is quite accessible for everybody. In fact, sometimes

it's so open that some groups take advantage of the system and

impose their own agendas at the expense of the greater American

interests.

|

|

|

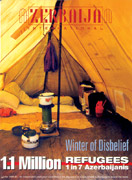

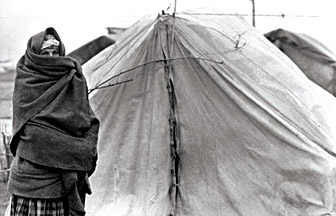

Left: Canvas tents were provided

for the hundreds of thousands of refugees who fled Armenian occupation.

However, since the tents were set up out on the open plains in

central Azerbaijan, they provided little shelter against exposure

to harsh climactic conditions - both the frigid cold of winters

and scorching heat of summers. The United Nations estimated that

approximately 700,000 Azerbaijanis were forced to leave their

villages and towns because of the war over Nagorno-Karabakh.

Photo by Oleg Litvin.

Right: Since fuel was extremely scarce and

survival depended upon it, refugees started cutting down trees

to prepare their food. Photo: Betty Blair, 1993.

The beauty of the system

is that all Americans have had an opportunity to express themselves.

And, of course, in my view, it has the most advanced system in

terms of serving people.

President Ilham Aliyev was officially invited to Washington in

April 2006 to meet with President George W. Bush at the White

House. That meeting highlighted the geopolitical importance of

Azerbaijan and gave a new and strong impetus to relations between

Baku and Washington. A broad spectrum of issues was discussed

during that meeting, including energy development, regional security

and non-proliferation of WMD (Weapons of Mass Destruction).

Despite the fact that November 2005 Parliamentary Elections had

many novelties that were implemented for the first time such

as the allocation of free airtime on state television to all

candidates, the marking of fingers of those who had voted with

invisible ink, the conducting of exit polls, opposition parties

and some members of the Western media were preparing themselves

for an Azerbaijani "color revolution".6

It didn't surprise me at all to read articles published in some

U.S. media outlets that expressed disappointment over the fact

that they did not see a "color revolution" in Azerbaijan.

I could not stop wondering about the whole idea of "democracy

promotion" that the U.S. administration was propounding.

The idea of spreading democracy and freedom in today's world

is a genuine and natural thing. I could not agree more with President's

Bush's remarks at his meeting with President Aliyev at the White

House, when he said that "Democracy is the wave of the future".

I share and applaud his personal commitment and desire to see

the rest of the world free and democratic.

However, the U.S. President's current strategy - the doctrine

of promoting democracy as he is doing it around the globe brings

to mind the Soviet Union's doctrine of spreading communism under

Leonid Brezhnev7 in the

1960s and 1970s.

Revolutions will not resolve the chronic problems of a country

if that country lacks a strong institutional foundation or basic

understanding about democracy itself. Honestly, even after working

so many years in Washington, I still don't understand many aspects

of democracy, especially, the dangerously growing role of money

in it. Or how can one justify the exceeding influence of ethnic

politics impact on American foreign policy?

I think many supporters of "color revolution" in Azerbaijan

even began to have second thoughts about this method of change

after seeing that the situation in some "color revolutionized

countries" had not changed much but had even worsened in

some cases.

To expect Azerbaijan to achieve such a democratic system fast

enough to satisfy some of the American officials is also somehow

a simplistic approach, especially given the Soviet system that

we have just begun to rid ourselves of. But sometimes those who

are in White House or the U.S. State Department seem to be rushing

to see the results of democratization under their own immediate

watch.

|

Left: Nearly one million Azerbaijanis

were made homeless in their own land because of the Nagorno-Karabakh

War with Armenia. Photo: Oleg Litvin, 1993.

Every society, every nation

has its own pace as it marches towards democracy. And in my view

that's what is happening in Azerbaijan now. I want to emphasize

that the trend is in the right direction. We are going the right

way towards democratization.

I'm glad that President Ilham Aliyev's visit to the United States

convinced Washington that he genuinely shares the same values

and aspirations for freedom and democracy and sees the future

of Azerbaijan, in his own words, "as a modern, secular,

democratic country." I'm also very pleased that President

Aliyev's successful visit was my "last accord" as an

Ambassador of Azerbaijan to the United States. By the way, this

final visit that I helped to organize was the eighth visit of

an Azerbaijani President to the United States during my tenure

in Washington.8

|

AI: You served as Ambassador

in the United States for 14 years. During that same period, there

have been six different U.S. ambassadors.9 assigned to Azerbaijan. You've also

served during three Presidential terms and two Presidents - Bill

Clinton and George W. Bush. That's an enormous difference in

terms of years in a position to understand the complexity of

that particular society.

Yes, you're right. Azerbaijan's

situation was unusual. We didn't have any experience in foreign

policy when I first became Ambassador. We had no well-established

diplomatic training. Actually, we had no embassies. For that

reason, we were obliged to use the individuals chosen to serve

as ambassadors as long as possible.

In my situation - as you may know - I requested President Heydar

Aliyev to release me after his official visit to Washington in

1997. But the President told me that we needed more time to educate

the American public, especially in regard to Section 907 and

that I should continue awhile as it would take time for a new

ambassador to learn the job. Well, that "little while"

turned into eight-nine more years.

The United States, of course, has an absolutely different situation.

The American government can draw upon many capable, well-trained

individuals to fill their positions of ambassadors. They have

some very well-established policies that determine how many years

each ambassador should spend in a particular country.

AI: What major differences

did you observe in the U.S. government's attitude toward Azerbaijan

during the different Presidential administrations?

Ambassador Pashayev: Well, Bill Clinton represented the Democrats;

and George Bush, the Republicans. In terms of relations and policy

towards Azerbaijan, I can't say that I observed any major difference.

As you know, President Clinton did a great job in supporting

the energy policy of Azerbaijan. As a result, we were successful

in signing what we call "The Contract of Century" for

the development of the giant oil field Azeri, Chirag and Gunashli

(ACG) and in putting forward the global project of Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan

(BTC) pipeline route.

President Bush did much less than Clinton in terms of oil. It's

easy to explain because in 2001 after the 9/11 (September 11th)

attack on the World Trade Center in New York, he focused on organizing

a coalition against terrorism. So, terrorism became the major

issue in relations between US and Azerbaijan. For both administrations,

I have no complaints in terms of their attitude towards Azerbaijan.

Both administrations opposed Section 907. Their position was

very clear. They opposed these sanctions. It was Congress who

had put them in place and maintained them.

|

|

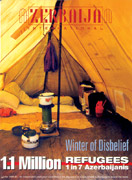

Far Left:

Azerbaijan

International devoted two entire issues to the refugee problem:

Spring 1994 (Winter

of Disbelief),

and Left:

Spring 1997

(Refugees

Revisited).

Many articles about the refugee situation can be accessed on

our Web site. Search at AZER.com

AI: You've only been back

a few weeks in Azerbaijan [August 2006]. What do you sense are

the deepest concerns among the local population in relation to

the Middle East and the U.S.? After all, there are so many major

crises: Palestine, Afghanistan, Iraq, and now Lebanon. Azerbaijan

is geographically located rather close to each of those countries.

Being a Muslim country - though quite secular in nature - but

nevertheless, Muslim, what do you sense are the feelings among

general population towards these volatile situations?

|

Ambassador Pashayev: The U.S. has put itself in a very difficult

position, especially in relationship with the war in Iraq. No

one knows what might happen next, but let me respond by saying

that in 1975 when I first visited the U.S., it was very clear

to me that the spread of American ideals attracted everyone.

I remember the old Soviet days. It was these American ideals

of justice and human rights that made us so keen to listen to

radio broadcasts such as Voice of America and BBC. Keep in mind

that it wasn't so easy to gain access to such information.

But now since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the U.S. remains

the only Super Power of the world. And somehow, I don't know

how it happened, but they started to rely entirely on military

might, rather than diplomatic power.

These days there is often talk about the U.S. trying to conduct

war simultaneously on two or three fronts in different parts

of the world. Of course, maybe they can achieve this from military

capability (instead of strategic) point of view, but they are

losing the good will and trust of nations worldwide. I think

it's much more effective to persuade people of ideas diplomatically

than militarily. In my view, Americans are at risk of losing

some of their ideals and basic principles of democracy by going

down such a path. Their losing what attracted the world to them

- "the American dream," "the American way of life,"

"the America that we used to know". Especially now.

AI: So, in Azerbaijan do

you sense negative feelings towards the U.S.?

Ambassador Pashayev: I wouldn't call it "negative",

but there is immense "disappointment". But, of course,

our government and the majority of people here understand that

Azerbaijan and the U.S. should work together. The role of diplomats

is to facilitate and help people become aware of the importance

of our relationships.

AI: More and more lately, we hear that the U.S. is making

plans to attack Iran, claiming that if Iran gets access to nuclear

weapons they will be a threat to the region. In your opinion,

if the U.S. does attack Azerbaijan's neighbor to the south, how

will this affect Azerbaijan?

Ambassador Pashayev: First of all, let me emphatically say

that the idea of the U.S. attacking Iran is not a good idea at

all. The disputes and difficulties that exist between the U.S.

and Iran must be resolved by peaceful diplomatic means. All difficult

issues must be resolved peacefully.

If the U.S. were to attack Iran, of course, there would be enormous

implications for Azerbaijan. Very negative implications and I

would not advise such action. If officials in the U.S. were to

ask our advice, categorically, we would advise against any such

attack. It's not a good idea, and there would be very serious

and negative repercussions for Azerbaijan.

As you know, Azerbaijan already has so many refugees. Nearly

one million people in our small country of eight million people

have been displaced because of the Armenian war over Nagorno-Karabakh.

We don't want to revisit those tragic days. We had enormous problems

trying to house and feed so many hundreds of thousands of people

on limited resources. To this day, we bear the scars of that

calamity.

Should there be an attack against Iran, no doubt there will be

a flood of Iranians coming across our borders to seek refuge.

This would be humanitarian disaster for Azerbaijan.

Openness and dialog is the way to bring opponents and adversaries

to your side. Through communication. Through discourse. Those

are much more effective ways than to attempt to use military

might. Earlier, I mentioned about the image of U.S. in the world.

Any new attack will create enormous complications and difficulties

even for the U.S. itself. It's absolutely not the correct path

to go in order to achieve stability in the region.

AI: Now that you're back

in Baku, what are your plans for the future? Are you retiring?

Ambassador Pashayev: Actually, after so many years in Washington,

I think I deserve to get out of any business related to the government

so that I can have some free time to enjoy life. And that's exactly

what I was gearing up to do when I returned to Baku this summer.

I've had enough. I was yearning to have a chance to live a private

life with my family.

I'm grateful to three successive presidents of Azerbaijan - Abulfaz

Elchibey (1992-93), Heydar Aliyev (1993-2003) and Ilham Aliyev

(2003-) - who trusted and honored me with the opportunity to

represent my country in the world's sole remaining power center

at such a crucial time in our history. It has been a privilege

to serve in this capacity. To be honest, admittedly, it is a

bit sad to be leaving such a major part of my life behind. But

the time is ripe to move on and clear the playing field for others

who, undoubtedly, will continue in what hopefully has been my

humble contribution to the thriving alliance between our two

nations.

But then the idea has begun to take shape that we should take

advantage of those many years in Washington and utilize my experience

to do something useful by helping to create a Diplomatic Academy

in the Foreign Ministry. President Ilham Aliyev supported the

idea and I have been asked to lead this process. Though this

idea was something new that I had to think about, I realized

how important it would be for Azerbaijan and for diplomacy, not

only for international relations actually, but for all Azerbaijani

government structures to have a school which would help to provide

concrete knowledge of the modern world in a modern education

system.

And so now, I have committed myself to this goal. My plan is

to create something not only for Azerbaijan but a school that

could be used to train diplomats in the region and, perhaps,

even beyond. I am currently working with friends in the U.S.

from various universities to come up with some ideas of how to

structure such an institute.

We're in the process now. Of

course, I want to build something new for Azerbaijan a

new university campus. I think it's very important to establish

a diplomatic college based upon international standards. And

I see it being developing in various stages.

Of course, intitially, we would

like to organize executive programs for our diplomats in the

Foreign Ministry and other ministries of the Azerbaijani government,

for those who need international training.

I visualize the second stage

being the development of a graduate school, with a Master's degree

program. The third stage would be to create a full-scale university-type

institution, offering a Master's degree in International Relations.

My greatest dream now is for this Diplomatic College to become

a center of excellence.

Life is education in every sense.

So, of course, we must share our experience with the young generation

and I think the best way to share our diplomatic experience will

be through this Academy.

_____

Footnotes

1

The White House deemed

that the "Freedom Support Act" was a "once-in-a-century-opportunity"

to help freedom take root and nourish in the lands of Russia

and Eurasia whose success in democracy and open markets would

directly enhace our own national security. The growth of freedom

there would create business and investment opportunities for

Americans and multiply the opportunities for friendship between

our peoples." See the Press Release Fact Sheet announcing

the passage of the Freedom Support Act passed on October 24,

1992. Visit: Federation fo American Scientists at http://fas.org/spp/starwars/offdocs/b920401.htm.

2 The 15

former republics of the Soviet Union: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus,

Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania,

Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan.

Of these, only the government of Azerbaijan was denied U.S. assistance

during this critical period of transition from a centralized

government to a market economy.

3 For a

discussion about the content of these UN Resolutions 822, 853,

874 and 884, see "The Nagorno-Karabakh Question: UN Reaffirms

the Sovereignity and Territorial Integrity of Azerbaijan"

By Yashar T.Aliyev [UN Representative at the time], AI 6.4 (Winter

1998). Search AZER.com.

4

In 2003, Azerbaijan

sent 160 troops to Iraq as part of what President Bush called

"The Coalition of the Willing".

5 Monica

Lewinsky: A young woman with whom President Bill Clinton had

a sexual relationship in the White House for four months betweeen

1995-1996. The scandal that broke out resulted in Congress trying

to impeach him but in the end he acquitted and remained in office.

Clinton remained popular with the public throughout his two terms

as President, ending his presidential career with a 65 percent

approval rating, the highest end-of-term approval rating of any

President since Eisenhower. Source: Wikipedia: Oct 10, 2006.

6 "Color

Revolution": Refers to the general non-violent change of

government via elections and alleged people movements that recently

occured in a few of the former Republcs of the Soviet Union.

These include the "Rose Revolution" in Georgia in 2003

that ended the Presidency of Eduard Shevardnadze, the "Orange

Revolution" in Ukraine, which ended with the election of

Viktor Yushchenko in 2004-2005, and Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan,

which led to the overthrow of Askar Akayev in 2005.

7 Leonid

Ilyich Brezhnev (1906-1982) was the effective ruler of the Soviet

Union from 1964 to 1982, though at first in partnership with

others. He was General Secretary of the Communist Party of the

Sovet Union from 1964 to 1982, and was twice Chariman of the

Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (head of state), from 1960 to

1964 and from 1977 to 1982. Source: Wikipedia on October 10, 2006.

8 Eight

presidential visits: six with President Heydar Aliyev (whose

presidential term in office was 1993-2003) and two with his son

Ilham Aliyev(2003-).

9

U.S. Ambassadors appointed

to Azerbaijan: Richard Miles (1992-1993), Richard Kauzlarich

(1994-1997), Stanley Escudero (1997-2000), Ross Wilson (2000-2003),

Reno Harnish (2003-2006), and Anne Derse (July 2006-).

_____

Back to

Index

AI 14.3 (Autumn

2006)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|