|

Winter 2006 (14.4)

Pages

58-65

Under

the Sea

Hidden

Treasures

First Expeditions Beneath the Caspian

by Dr. Viktor Kvachidze

(pronounced kva-CHID-ze)

And

just what did ancient man think about this vast body of water

that today we call the Caspian Sea? When we delve into old manuscripts,

we discover that they were, indeed, very puzzled about the Caspian.

Of course, today we know that it really is a lake and not a sea

at all. The Caspian has no outlet into any ocean, so technically

speaking, it isn't a sea at all despite its name. And

just what did ancient man think about this vast body of water

that today we call the Caspian Sea? When we delve into old manuscripts,

we discover that they were, indeed, very puzzled about the Caspian.

Of course, today we know that it really is a lake and not a sea

at all. The Caspian has no outlet into any ocean, so technically

speaking, it isn't a sea at all despite its name.

People in ancient times wondered if the Caspian was somehow connected

to oceans in the frigid north. Alexander the Great from Macedonia

(356-323 BC) is said to have been curious to know if the Caspian

Sea flowed into the Arctic Ocean. They say that he even attempted

to organize an expedition to explore this possibility. However,

the first known expedition to map the Caspian was actually carried

out by the Russian explorer Patrokov (283-282 BC).

Even though he never succeeded in reaching the northern-most

tip of the Caspian shores, he was the first person ever to attempt

to measure this vast body of water. He found it to be 435 kilometers

(270 miles) at its widest part, and 1025 kilometers (637 miles)

long.

As the northern part of the Caspian becomes very icy in winter,

this is probably the reason why Patrokov was not able to complete

his mission pushing further north to understand if there were

any relationships between the Caspian and other bodies of water.

So he could not confirm whether or not it flowed into the Arctic

Ocean.

Click on photos to enlarge:

Under the Sea

But it wasn't until Frenchman Jacques Cousteau (1910-1997) invented

the first scuba diving equipment known as the aqua-lung in 1942-1943

that serious exploration could be carried out beneath the surface

of the sea. The aqua-lung enabled divers to explore underwater

at significant depths for extended lengths of time.

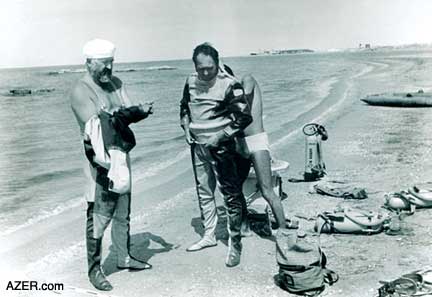

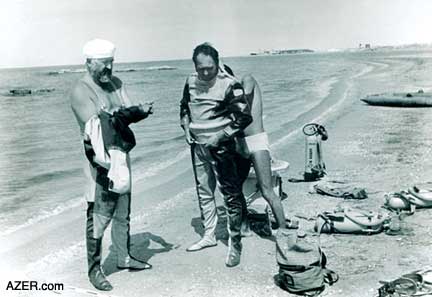

Above:

Getting suited up in preparation

to make a dive. Eastern coast of Azerbaijan. Left: Gennadiy Pastumkov

and Victor Kvachidze, 1972.

Cousteau captured the imagination

of the world with his famous popular TV series, "The Undersea

World of Jacques Cousteau". In the Soviet Union, we also

watched. Cousteau's underwater explorations made such an impact

on us as young people that some of us even tried to make diving

equipment ourselves. Cousteau opened up a new world for us. It's

to his credit that we were so determined to explore the Caspian.

Azerbaijan is an ancient land. As historians and archaeologists,

wherever we turn, we see evidence of early history and culture.

Because so much archaeological evidence in Azerbaijan can be

found on the surface of the earth, I was convinced that there

would also be an enormous body of evidence lying at the bottom

of the sea as well.

Then in 1968 I had the idea to create an underwater archaeological

expedition in conjunction with the Azerbaijani History Museum.

Both Pusta Azizbeyova, Director and Academician, and Yanpolski,

Head of our Department and Doctor of Historical Sciences, supported

this idea. Also one of the German specialists in the sphere of

underwater research was studying at the Higher Naval School and

he also became interested in underwater archaeological research

in Azerbaijan.

Our group was organized with the approval of the Committee on

Science and Techniques of the Soviet Union. A special plan was

worked out on the research of underwater archaeological monuments

and coastal monuments in the waters of the Caspian Sea in Azerbaijan's

territory by the Ministry and the Presidium. But organizing such

an expedition as well as training for it was not an easy task.

Maritime archaeology differs considerably from traditional archaeology.

Not only does it require enormous depth and breadth in numerous

fields, but underwater archaeologists must also have a vast knowledge

about the sea and its currents and they must technically master

diving equipment as well.

Examples of ceramics found in the Caspian sea. Click to enlarge:

Various examples of ceramics

found in the Caspian sea. Many were painted with birds or animals

and geometric shapes. Some are believed to date back to the 12th

century. Archaelogists have identified three colorsmade from

a combination of natural oxides to create the colors: green,

purple and yellowish brown.

Photos: Blair/Ceramics from collection of underwater ceramics

at Azerbaijan's National History Museum/Victor Kvachidze

Getting Started

We had many things to learn. First, we had to study what our

own Soviet scientists knew about maritime archaeology. Then we

had to learn about diving equipment, where to procure it and

how to use it responsibly to prevent any serious accident or

even death. Then we had to get all the official approvals for

this kind of investigation. All these things were necessary to

accomplish even before starting any expedition or project.

So several of us headed off to Leningrad (now St. Petersburg)

and Moscow to acquaint ourselves with the work of V.D. Blavatskiy

(-1987), a professor of Historical Sciences and the first person

in the Soviet Union ever to carry out underwater archaeological

projects. Blavatskiy had explored the Black Sea and authored

such books as "Ancient Archaeology of the North Black Sea

Coastal Area" (Moscow 1961) and "The Towns of the Bosphorus"

(Moscow 1952-1958). In addition, he had written numerous articles

about his underwater archaeological expeditions. So that's how

we got started.

The First Dive

Then we were faced with the question of where we should plan

our first underwater investigation. The first dive was organized

in 1969. From medieval times, a number of writers had observed

that there were monuments submerged along the Caspian shores

of Azerbaijan. For example, we have manuscripts that describe

about the Bayil [sometimes referred to as Sabayil or Sabail]

monuments belonging to a fortress or caravanserai in the Baku

Bay. They had sunk sometime between the end of the 13th century

and beginning of the 14th centuries [See: "Mystery of the

Sunken Castle Sabayil: Many Questions Still Plague Archaeologists"

by Sakina Nasirova, Azerbaijan International, 8.2 (Summer 2000).

Search at Azerbaijan International's Web site AZER.com].

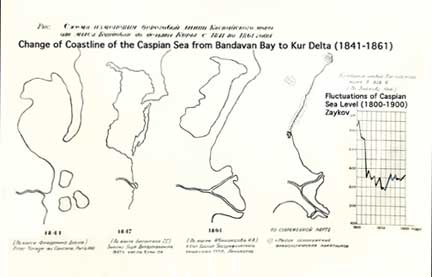

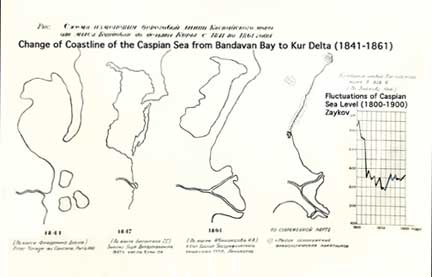

Above: Variations in the coastline of the Caspian

Sea from Bandavan Bay to Kur Delta (1841-1861). Also Fluctuations

of the Caspian Seal Level in the 20th century, according to research

by Zaykov in 1946.

Several medieval authors, including the Persian-speaking scientists

Idrisi and Mahsudi, noted that certain towns and villages had

been submerged in the estuary of the river Kur.

Other research led to the Venetian statesman and geographer Marino

Sanuto who is sometimes referred to as Sanuto the Elder of Torcello

(ca.1206-1338) [Wikipedia: "Marino Sanuto", February

10, 2007]. Sanuto had drawn a map of the Caspian noting the most

significant towns and villages along our southern coastline that

had been flooded and were submerged in the sea. So all these

medieval manuscripts helped us tremendously in our own research.

There is also mention of some of these flooded towns in the works

of Abbasgulu agha Bakikhanov, Abdurrashid Bakuvi and others.

I was curious to study such phenomena. In the process, I believed

such an investigation would reveal knowledge about ancient navigation

and also provide information about how early people made use

of the shoreline and what their coastal towns looked like.

But where were these hidden cities located? Where should we start

diving? Where would the best location be to start our underwater

investigation? We decided to ask the local fishermen and the

people living along the coast to see if they could provide clues.

So we described our project in local newspapers asking if anyone

had seen any construction or monuments lying at the bottom of

the sea.

The advice from fishermen was exceptionally helpful. They kept

telling us that where they set their nets they often found a

lot of ceramics under the water. So, we started our exploration

there in the Kur River estuary that feeds into the Caspian, since

this water way originates in Georgia and transverses the length

of Azerbaijan. Both archaeological as well as historical literature

suggested that at one time there had been a connection between

the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea via the Kur and Rioniya Rivers

(the Georgian name for the Kur).

At first we explored nearby the seacoast, thinking there might

have been a settlement nearby. Gradually, we moved out away from

the coast. We were given the vessel of Volodya Dubinin from the

Marine Technical School for the expedition. When we got out of

the boat and approached to the coast, we could feel pieces of

ceramic under our feet. At every our step, something broke under

our feet. Had we had a truck there, I believe we could have completely

filled it with pieces of ceramics.

Difficulties

Despite how exciting such diving expeditions might sound, we

experienced countless difficulties. Even the mere task of acquiring

scuba diving equipment during Soviet time was difficult. Finding

scuba diving suits was a problem, too.

However, nothing could compare with our knottiest problem of

getting compressors, which function to pump air into the aqua-lung

equipment. More importantly, we had to make sure that they didn't

break down on us. We had no compressors here in Azerbaijan so

friends from Moscow brought them to us. But, frankly speaking,

even these compressors were a big headache for us! Something

always seemed to go wrong with this simple equipment. It was

in a constant state of disrepair, which, of course, could have

endangered our lives.

Our rudimentary equipment enabled us to dive for sessions of

about 30-40 minutes. We still have this equipment that we used

nearly 40 years ago. When the History Museum reopens, we'll put

that old scuba diving equipment on display in a section devoted

to maritime archaeology. [Currently, major repairs are going

on in the Taghiyev Residence where the History Museum material

is exhibited on the ground floor.]

Decompression

Even though our equipment

supposedly could have enabled us to dive to depths of 45 meters,

we tended to be rather conservative in taking risks and didn't

go deeper than 20 meters. Simply, we didn't have decompression

chambers. We were always careful to follow the known rules related

to decompression and diving safety when our divers resurfaced.

The decompression process is critical when diving. When a person

surfaces after having been submerged for a significant amount

of time, one's veins can burst from changes in the water pressure.

In fact, scientists have even found bloodstains on animal bones

at depths of merely three or four meters. So injuries can occur

even in animals if they surface too rapidly.

For greater depths, divers need decompression chambers. Our team

didn't have access to them. That's why we couldn't dive very

deep. During our expeditions, we did find evidence of sunken

ships but, unfortunately, we didn't have the capability to explore

the wreckage. To this day, most of the shipwrecks have yet to

be investigated. We did find one wreck located at a depth of

45 meters between Jilov and Pirallahi, the two largest islands

of the Absheron archipelagos.

Another problem that we faced during our dives were the strong

underwater currents. The Caspian can be quite unpredictable.

Winds can whip up suddenly and separate the boat from the divers.

But, in general, our expeditions were carried out without any

major mishaps or life-threatening incidents. We were fortunate.

One of the unique aspects related to conducting maritime archaeology

has to do with the influence of waves and underwater currents

on the placement of submerged objects. With archaeology carried

out on land, you can always count on coming back day after day

and finding your object of study always there.

But with underwater archaeology, sometimes divers need to return

to the very same location several times. It's possible not to

find anything one day but then to return and dive again - sometimes

even a few weeks later - and make valuable discoveries. That's

exactly what happened with us once at Amburan [Absheron Peninsula]

where we found many anchors after a storm. We had been diving

in one specific place many times with nothing significant to

show for our efforts. Then a strong northerly wind blew for about

a week. We returned and went down exactly at the same location.

This time we discovered that the wind had pushed away much of

the sand and exposed many anchors at the bottom of the sea. It

was an amazing find. Our persistence paid off. Even today, Azerbaijan

still does not have the necessary equipment to adequately explore

underwater even in relatively shallow waters. Furthermore, there

haven't been any underwater archaeological expeditions for the

past 20 years in Azerbaijan. By 1987, the Soviet Union was on

the verge of collapse and funding was completely cut off.

Then the Karabakh War started in 1988, so we couldn't carry out

any expeditions. But we still went and made dives here and there,

but such attempts were carried out only on a personal basis,

not as official government-sponsored expeditions. Then the Soviet

Union collapsed in late 1991. The fact is that not a single maritime

archaeological project has been carried out since we gained our

independence.

We also had difficulties finding adequate transportation to take

our team and equipment out to the various sites. Then there were

the logistics of acquiring adequate supplies and the preparation

of food while on location. As head of the expedition, I was always

distracted by those problems. There should have been a special

person who was assigned to take care of all these daily logistics.

Fortunately, we had very good people on our team; everybody was

cooperative. We would assign two different people each day for

these mundane, but necessary, tasks related to food preparation.

Somehow, we always managed to have meals three times a day. And

whenever anyone caught any fish at the end of the day, we would

even enjoy a second dinner that evening.

Contributions to

Science

Despite these struggles and difficulties, we did manage to make

contributions to the science of maritime archaeology in the Caspian.

In 1998 when the History Museum sponsored our 30th Jubilee of

Maritime Explorations of the Caspian, we reflected on what we

had accomplished. We could take credit for several major accomplishments.

One is the investigation of submerged ancient cities that we

discovered at Bandavan 1 and Bandavan 2 in the Kur estuary.

We consider Bandavan 1 to be one of the newer cities of the Middle

Ages. This is the city of Gushtasfi (alternative spelling: Gushtaspi).

This city seems to have come into existence after the 12th century.

Many ceramic plates with illustrations of birds were found in

this town.

Bandavan 1 is archaeological name of the city Gushtasfi (or Gushtaspi);

Bandavan 2, for Mughan. The archaeological site called Bandavan

2 revealed a 9th century city called Mughan, which was located

on the three branches of the Kur River. It was a strategic location

and on a major trade route. We don't know what happened that

the city became inundated. Did the river change its course? Were

there cataclysmic events that made the inhabitants leave the

settlement? Or did they just simply decide to move to Gushtasfi?

We don't know with any certainty.

These discoveries also have contributed to our greater understanding

of the fluctuations of the Caspian Sea that have been occurring

for thousands of years. Every monument lying at the bottom of

the sea provides additional evidence about the rise and fall

of the sea. It helps us reconstruct a historical chronology of

the sea's fluctuations. Such information assists us in charting

both the highest and lowest points of fluctuation. [See "Fluctuating

Levels of the Caspian Sea" by Mirzakhan Mansimov and Amir

Aliyev, Azerbaijan International, Vol 2.3 (Autumn 1994). Search

at AZER.com].

Twelfth Century

Ceramics

Another significant contribution was our discovery of ceramic

pottery. We found many plates and bowls painted with birds. Most

of them date back to 12th and the beginning of 13th centuries

AD. This is the period of flowering of Muslim renaissance, the

period of Nizami and the period of development of medieval Azerbaijani

towns and with this the development of pottery. We can see the

stamps of masters and sometimes their names on these plates.

For example, there were names such as "Kasagan Yusif"

(meaning, "Yusif", who created this), or "Ahmad".

Imagine, such artwork dates back to the 12th century. It means

that these ceramics are older than canvases painted by Leonardo

Da Vinci. Who can place a value on such rare artifacts? How would

you price such an artwork if it were painted on parchment or

canvas? Would you appreciate this? You would say "Ah, what

beautiful artwork!" These artists were true craftsmen. And

their colors are still vivid despite how many centuries these

ceramics have been submerged in the sea. And our contribution

is that we discovered these paintings and have worked to preserve

them for posterity.

Many ceramics are painted with images of birds and various animals.

From ancient times birds have symbolized happiness in both myths

and legends. Birds symbolized the sky and, therefore, were considered

to be sacred. There are a lot of paintings of doves; perhaps,

they were considered holy. Deer symbolized the sun; its horns

represented the rays of the sun. Fish represented abundance and

goodness. There were also a lot of cheetahs ("leopard"

in Russian). Poems were painted on some of them. For example,

there is a poem of Saadi (Persian poet) on one of the plates:

"Don't stand so proud in front of me, you Beauty. Once,

I was also a flower in this garden."

However, as time passed, symbols changed but the tradition of

painting these symbols remained. Artists didn't draw images of

birds for their meaning but rather because it had merely become

a tradition to do so. A close look at the plates on which birds

are painted and you can see that they are quite stylized. And,

in general, they always face towards the right, not left, direction.

Still the artists manage to express their own individualism in

each work.

The diameter of plates is up to 28-30 cm. and the cups measure

between 12-18 cm. As we see all of the ceramics of this period

are covered with a glaze consisting of a white material called

"angob". This is a thin layer of clay which is spread

over the surface of the ceramic object to intensify the colors,

and make them look even brighter.

Three colors dominate these ceramics-green, yellowish brown and

purple. These colors were created with oxides and today, the

colors are still quite vivid. Green was created with copper oxide.

Various shades of yellow and brown were made from ferric oxides.

The violet color (which was used the least of all) was made from

manganese oxide. Mainly artists used these colors and were so

skillful in combining these oxides to create very colorful drawings

on the pottery.

I compared the sketches of birds, animals that we found on ceramics

at the Bandavan 1 site with found in other cities of Azerbaijan

and also Armenia, Georgia, Iran. They are significantly different.

There is something unique about the art work in Bandavan. You

can sense the expression of independence and brilliance by the

artist in their paintings.

How can one explain this? Perhaps, the local people who settled

in this city were independent in character. The region was known

for its rice plantations in ancient times and it attracted many

migratory birds. It seems the artists were very observant which

is characteristic of ancient people. Nature inspired them back

then, just as it does today.

All archaeological artifacts are valuable in piecing together

history. One of the most interesting finds, however, in my opinion

is a small head carved from stone which dates back to the Bronze

Era, about 2nd century BC. It is one of the oldest artifacts

that we ever found during our underwater expeditions. It was

discovered at Sangi-Mughan and bears resemblance in technique

and features to other carvings that have been found in Siberia.

We also found the remnants of pottery kiln there in Bandovan

1, equipment used in the oven during the pottery-making process

and a lot of pottery, which had not yet been fired.

The Situation Today

Even though significant archaeological work was carried out during

Soviet times, very little information was disseminated throughout

the world. Few people knew about the valuable findings that we

made here in Azerbaijan. One reason for this was that news primarily

featured the greatness of Russia.

Today, now that Azerbaijan has gained its independence, we have

more chances to contact museums and scientists in other countries

and to share our findings and cooperate in research together.

The major obstacle, however, is always financial. I hope that

some day expeditions will start up again as there is much evidence

of significant historical material lying at the bottom of the

Caspian Sea.

_____

Dr. Victor Kvachidze graduated

from Baku State University with a major in History in 1956. Later

he worked at the Naval School in the Chair of Political Economy

of the Communist Party of Soviet Union. While completing military

service, he also finished the School of Junior Specialists in

Fargana, Uzbekistan, where he specialized as an aviation mechanic.

Then he started working at a boarding school in Mardakan, near

Baku, as a tutor and teacher. He later was invited to work at

Azerbaijan's History Museum [housed in the residence of Oil Baron

Taghiyev in downtown Baku] loacted at 4 Taghiyev Street.

Today, the museum is Victor's second home. He's been working

there for 40 years, since 1967. In addition to his interest in

History and Underwater Archaeology, he is also very interested

in art and specifically African art. He enjoys carving masks

and various objects from wood. He also enjoys painting.

Victor has recently completed exhibits for the Azerbaijan History

Museum ranging from the Paleolithic period up to modern times,

as well as artifacts, especially pottery found during underwater

expeditions.

Ulviyya Mammadova and Gulnar

Aydamirova were involved in the preparation of this article and

photographs.

____

Back to

Index

AI 14.4 (Winter

2006)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|