|

Spring 2006 (14.1)

Pages

90-94

Stalin's Legacy

Dissolution of the Family. "Don't Wait for Me"

by

Naila Hasanova

One

of the saddest legacies of Stalin's policies was the dissolution of so

many families. Across the expanse of the entire Soviet Union,

millions of families were left broken and destroyed - even

when prisoners managed to survive and return home. It seems no

family was left untouched by Stalin's Repressions. One

of the saddest legacies of Stalin's policies was the dissolution of so

many families. Across the expanse of the entire Soviet Union,

millions of families were left broken and destroyed - even

when prisoners managed to survive and return home. It seems no

family was left untouched by Stalin's Repressions.

Naila Hasanova, 69, tells the story of her parents - Samaya and

Anvar - who enjoyed six difficult, but impassioned, years of marriage

before World War II separated them. Anvar survived the war front

although many Azerbaijanis didn't. But when he returned home,

the trauma wasn't over.

Soldiers who had been captured and interred in German prison

camps were viewed as "Enemies of the People" by the

Soviet regime because Stalin had ordered those in the military never to allow

themselves to be captured. And so immediately after returning

from the war, the soldiers who had been imprisoned were hauled off to Soviet hard labor

prison camps - sometimes for many years. Stalin used this as

a ploy to exploit his own citizens and use them as slave labor

to develop the natural resources, especially in less developed

regions of the country.

That's what happened to Naila's father Anvar Hasanov. After serving

three years in the war, he was sentenced to 10 years in a prison

camp near the Arctic Circle. Fearing that he wouldn't survive,

he wrote his young wife and encouraged her to remarry and save

herself and the two children.

Broken hearted, she followed his

advice. Many women faced the same dilemma. But Anvar did

survive the tortuous years of prison camp and he did return home,

only to face the painful reality that, indeed, the true love

of his life had remarried and, because of the circumstances,

she had done exactly as he had told her to do - not wait for him. Her daughter

Naila reflects here nearly 70 years later about the impact Stalin's

repressions had on her family.

Early Years

My mother Samaya (1913-1962) was a chemist and my father Anvar

(1913-1993) was an oil engineer.

They both were born in the same year. Both attended the same

high school and the same university, graduating from the Azerbaijan

Oil Chemistry and Industry Institute (now Azerbaijan Oil Academy).

My father graduated from the faculty of Oil Mine Engineering,

and mother took her degree in Chemical Technology. Her dissertation

was about the mysterious underground rivers that flowed beneath

the city of Baku.

So my parents fell in love and got married in 1935 although her

parents felt that they were too young. They had a crazy love.

In 1937 they gave a birth to a son Rufat, who died of measles.

Then I was born in 1938, and two years later, my sister Elmira

came along. My parents lived together for only six years.

At that time, father was working for AzNeft [AzNeft: An oil company

in Azerbaijan. The word "neft" means oil]. Actually,

during World War II everyone in Azerbaijan who worked in the

oil sector was exempt from serving in the military because Azerbaijan's

oil played a major factor in countering the Germans [Azerbaijan

contributed the majority of oil that was used in the Soviet effort

to defeat the Germans. Azerbaijan deserves much credit for their

incredible role in helping the Allies to gain the victory in

World War II].

But

my father had a sharp tongue. In one of the meetings, he started

complaining about the Soviet system, perhaps in a joking manner.

It was Stalin's era, and, of course, someone denounced him right

away. People often would report on each other just to gain favor

of those in high positions. Soon my father's exemption was removed

and he was sent off to the war. This happened in 1942. I was

four years old; Elmira was two. But

my father had a sharp tongue. In one of the meetings, he started

complaining about the Soviet system, perhaps in a joking manner.

It was Stalin's era, and, of course, someone denounced him right

away. People often would report on each other just to gain favor

of those in high positions. Soon my father's exemption was removed

and he was sent off to the war. This happened in 1942. I was

four years old; Elmira was two.

Father was sent to the Kerchi division in the Black Sea region

of Crimea. It was quite a famous division and most of the soldiers

were Azerbaijanis. But the Germans captured the entire unit.

My father was sent to Osvenson and Dakhao labor camps in Germany

as a prisoner of war. Father could have stayed on, found a job

and lived in Germany as he knew the language. But he came back

to Azerbaijan in 1945 for mother and us.

Then came Article No. 50, which declared that all soldiers who

had been prisoners of war in the enemy's land were considered

"Enemies of the People" back home. Since my father

had been held in German prison camps, that meant him and, predictably,

they came and arrested him.

Stalin insisted that soldiers should never allow themselves to

be captured; they should kill themselves rather than be taken

captive. But there were thousands of soldiers in the Kerchi camp

and the entire camp was taken. How could so many people kill

themselves? And why?

I'll never forget the day when the NKVD agents [Azerbaijan contributed

the majority of oil that was used in the Soviet effort to defeat

the Germans. Azerbaijan deserves much credit for their incredible

role in helping the Allies to gain the victory in World War II]

came looking for father. It was December 19, 1945. My sister

was only five years old but she also remembers it well. It was

such a traumatic experience that we never forgot despite how

young we were. The agents turned our house upside down. My sister

and I were sitting on the couch. They came in and searched the

whole house, ransacking the house and turning everything upside

down. They couldn't find anything. We didn't even know what they

were looking for - maybe guns, maybe letters from Germany. We

never knew. .

We had a little suitcase, and they told father to put his stuff

in it. Elmira asked: "Daddy, are you going to the bath house?"

Left: Samaya, the granddaughter of Naila's sister, who

was given the real name of her greatgrandmother. Finally, the

family is choosing this name again. The last generation associated

"Samaya" with too much pain brought on by Stalin's

repressions. Left: Samaya, the granddaughter of Naila's sister, who

was given the real name of her greatgrandmother. Finally, the

family is choosing this name again. The last generation associated

"Samaya" with too much pain brought on by Stalin's

repressions.

I was watching them with big wide curious eyes but I couldn't

understand what they wanted from us. And then they took father

away. Little did we know we would never see him again until 1956.

They kept father in Baku's Keshla prison until March 30, 1946.

We used to take him parcels but were never allowed to see him

or meet with him. Official documents indicate that on April 24,

1946, the court sentenced him to exile at Vorkuta, a city on

the Vorkuta River in the Autonomous Republic of Komi ASSR [The

Komi Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was established in

August 22 1921. It is located in northwest USSR close to Europe.

The climate is quite severe. The average temperature in January

varies from between 15 to 20C (5 to 4F), in July,

it ranges from 11 to 16C (52 to 61F). [Wikipedia: April 27, 2006].

In northwestern Russia close to Finland.

Later he told us that they had had to walk much of the way to

Vorkuta. It was called "etap", meaning "on foot".

Of course, they went some distance by train, horseback and even

dogsled, but they walked a considerable distance, too. Many prisoners

died along the way. Father was clever; he managed to stay alive.

He used to tell us stories of how they foraged for food to stay

alive. They would eat raw potatoes, tree bark, leaves, grass,

and roots of plants.

Father was not allowed to write us. Article No. 58 denied permission

to the Prisoners of War to correspond, but somehow he managed

to send us two letters during those 10 years he was in exile.

We received the first letter in 1948 while we were living in

Shusha. He had passed it through various people, not the post

office.

I remember the day that it came as if it were only yesterday.

I was 10 years old. My little sister and I were sitting together

and mother read it to us. Father wrote that they were living

under very bad conditions and that they had been told that they

would have to stay there for the rest of their lives. He told

mother not to wait for him and to marry someone else, and to

create a good life for all of us.

In the second letter that arrived three years later, father let

my mom go free because he doubted that he would ever come back.

He knew that we were suffering a lot because we had his last

name. Again, he told her to try to make a good life for us, and

to change her last name and ours. That letter was very painful

for mother; it must have been the same for father.

Our apartment in Baku was close to the sea. It was in a big,

old house near Taghiyev's Musical Comedy Theater [Taghiyev's

Musical Comedy Theater was rebuilt in 1998. It is located on

Neftchilar Avenue not far from the Marionette Theater and Maiden's

Tower]. One of the apartments on the first floor used to be ours,

but the government took it from us and left us only with one

room. Other people were assigned to live in the other rooms.

What could mother do?

And then the order came telling us to go to the NKVD office because

they were gathering all the families of "Enemies of the

People" so that they would leave the country for Kazakhstan.

They gave us 24 hours. It was 1948. My mom had strong relatives.

My mother's sisters were doctors and in a strong financial position.

They gathered and decided that they must find a way so their

sister would not be exiled from the country. They were so afraid

that we would all die on that long harsh journey to Kazakhstan.

Mother was a small, fragile woman.

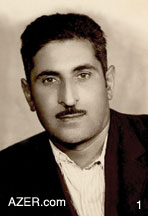

Stalin's Repressions

devastated so many families and broke up so many marriages: (1)

Anvar Hasanov (1913-1993), (2) Samaya Hasanova (1913-1962) who

later married (3) Mustafa Mammadyarov. Anvar was Samaya's first

husband and deep love throughout her life. They had two children

before he went off to World War II. When he returned, Stalin

sent him off to labor camp because his unit had been captured

in Germany. The government policy required that the wives of

such prisoners should also be sent into exile with the children.

Mustafa Mammadyarov who had known Samaya since youth rescued

the situation by marrying her and providing for her children.

But then Anvar returned to discover that no family was waiting

for him. Despite Samaya's love for her first husband, she did

not return to him because of the kindness of her second husband

through all the difficulties. Samaya's children are convinced

that the stress of this situation is why she died of cancer at

the young age of 49.

Fortunately, she was quite attractive and men liked her. Many

of them had been friends with her and my father since high school.

Among them, there was one - Mustafa Mammadyarov - who loved mother

very much. He knew the entire history of our family. He was divorced

so he asked mother to marry him and promised to take care of

us two girls. Actually he was the only one who promised to take

care of us, her daughters. And he did his best, he really did.

That way we could change our last name and not be exiled to Kazakhstan.

Within the allotted 24 hours mother went and registered the marriage

and officially changed her last name. They weren't actually married

yet, but the agreement was official. The marriage took place

later.

|

"Father wrote

that they were living under very bad conditions and that they

had been told that they would have to stay there for the rest

of their lives. He asked mother not to wait for him, but to make

a good life for herself and us children."

-Naila Hasanova,

describing the terrible dilemma that her mother face when her

husband was sent into exile.

|

Mother's relatives insisted that she do this. Her second husband

Mustafa was also an oilman just like Anvar had been. Mother changed

her last name, but we children kept ours. Now mother was no longer

the wife of an "Enemy of the People", and we didn't

have to deal with the problems that we had faced earlier.

Father was trained as an oil engineer, but in Vorkuta where there

was no oil, he worked in the coalmines. He became good friends

with some of the German prisoners of war because he knew their

language so well. The Administration of the camp used my father

as an interpreter. In 1949-1950, they started returning German

prisoners back to their country. Up until then, the Germans had

labored all over the Soviet Union and constructed many of the

buildings [Buildings that German prisoners built can still be

seen in Baku, the most well-known of them is the Government House

on Neftchilar Avenue near the Caspian].

My grandmother went to visit my father in the Arctic polar camp

in Vorkuta, Komi. She was a real heroine. She gathered all the

necessities she thought he might need, and took a train to Moscow.

The journey from Baku to Vorkuta took her 18 days. I don't know

what kind of transportation she used but she was determined to

find her son and to make sure that he was still alive. After

that, she returned to Baku. A year later, she went to visit him

again.

And then father came back home. The hardest part for mother was

when he came back. Imagine her situation. She loved him so much

but now she was married to someone else and had a child by this

second husband who for years had so kindly protected her in this

personal crisis.

|

|

Above: Samaya Hasanova's descendents: (From

left, sitting): Naila's half sister Zemfira (Mustafa's daughter),

Zulfiyya (daughter-in-law of Elmira), Naila Hasanova who authored

this article, Zemfira's daughter Sona. Standing (from left):

Naila's sister Elmira, Naila's daughters: Nargiz and Samira.

Right: Jamila (Naila's granddaughter). Photo:

2003.

Psychologically, it was almost unbearable for her. Who can comprehend

her pain? Who can understand her heartache? My sister and I analyzed

the situation for many years after her death, and we think that

she developed brain cancer because she had to deal with so much

stress in her life. She really died at a very young age - 49

- in 1962, only six years after father returned.

We saw father a lot after he returned. We used to spend time

together. He used to see mother, too, but only at large gatherings

such as weddings, funerals. They had common friends as they knew

the same people and moved in the same circles. When mother died

in 1962, father would go to the cemetery every day and place

one flower - just one - on her grave. He did that for two years.

We children wouldn't let her go back to father. We figured that

we had grown up without a father and didn't want our younger

sister to grow up without having a real father. We thought that

our little sister should live with her real father. Though we

were proud of that decision at the time, now that I look back

on it, I think it probably wasn't the wisest thing. Mother suffered

so much. She loved my father - her first husband - throughout

her whole life.

My father was deeply pained as well. He waited for mother to

come back to him. He really believed that their love was so strong

that she would do it. But then she became ill and died. Father

remarried two years later, in 1964.

When father came back from the war front in 1945, I was only

seven years old. I didn't understand so many things at that time.

But I was 18 by the time he returned from Siberia in 1956, and

I could comprehend what was happening.

After father returned home in 1956, like other prisoners of war,

he was not allowed to live in any major city. They sent him to

Ali Bayramli, about an hour and a half south of Baku. He worked

in NGDU as head engineer. Fifty years ago, he was involved in

the discovery of oil in Ali Bayramli. He continued to live there

for two years (1956-1957). After that, he was allowed to settle

back in Baku where he worked for AzNeft on the island of Peschani.

After Khrushchev's death in 1964, the government started to send

professionals to various foreign countries to work. Decisions

were made in Moscow. They called father there and told him that

they wanted to send him to India as an advisor on a major oil

projects. So he went to India in 1969.

|

"I always tell

these stories to my grandchildren. I want them to know who their

grandmother was. I want my children and grandchildren to be like

her. 'You are the grandchildren of Samaya,' I tell them. This

is the greatest legacy that she could ever have given us - the

model of her life, even under incredible duress."

-- Naila Hasanova

|

He worked there for five years

and helped to establish an offshore petroleum project for them.

He even received a gold medal from Indira Ghandi acknowledging

his work. Later, he worked in Czechoslovakia and received a Czech

medal, too. After that, he worked in the Romanian oil sector.

After mother died, we introduced father back into our family.

This had been impossible prior to her death. After that, my stepfather

and father became friends. They both had suffered the same grief

when she died, but then they became very close friends.

Stalin's Legacy

Today

So many of Azerbaijan's smart, intelligent, talented people were

wiped out. That's Stalin's legacy to us today more than 50 years

after his death. Many of our most capable individuals died in

camps, and even those who returned home after many years, usually

did not live much longer. Look at mother who was left to have

to cope with all of these things. She died from stress. I'm convinced

that her cancer came from stress.

In regard to Stalin, when I was growing up, a personality cult

had developed around him. I attended a Soviet school where Stalin

was like God. I was a kid and didn't realize that everything

that my family had suffered was because of Stalin. In 1953, when

Stalin died I was in the 7th grade. The entire class was sitting

there, crying. I was crying, too. I didn't know that Stalin was

responsible for all these repressions.

Above:

Anvar with his mom in 1955,

the second time she went to visit him in the prison camp. Twice

she made journeys alone to the arctic labor camps to find her

son Anvar. The trip took her 18 days. Naila calls her grandmother

a "heroine".

Imagine when Khrushchev announced at the 20th Congress in February

1956, three years after Stalin's death that Stalin had organized

all these repressions. All of us were in shock. We couldn't believe

it. We didn't know that Stalin was the one responsible for all

our pain. We always thought that those who were arrested or killed

during those years were real "Enemies of the People".

At the 20th Congress Khrushchev exposed and condemned this personality

cult.

Every person in Azerbaijan has painful stories about the repressions.

Unfortunately, there's not a single book where all these stories

have been collected. Mehdi Husein was the only Azerbaijani writer

who dared to write a novel about the repressions during the Soviet

period. It was published in 1966, a year after he died. Its title

is "Underground Rivers Flow To The Sea". It's really

about my mother. My mother and Mehdi's wife Fatma had been friends

from childhood.

Mehdi Husein as editor of Azerbaijan Literary magazine first

published "Underground Rivers" in chapter sections

in 1964. Unfortunately, he did not live to see his book come

out in book format. The following year when he was only 56 years

old, he had a heart attack right in front of an assembly of the

Writer's Union - when some of the outspoken figures attacked

and sharply criticized him.

Mehdi had intended the book to be published in Russian to have

broader distribution. Amazingly, the novel did come out in 1966

in book format - one edition. [Solzhenitsyn had published "One

Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich" in 1962 but only with

the authority of Khrushchev who was trying to strengthen his

own position and undermine Stalin's.

Solzhenitsyn's "Gulag Archipelago" appeared as a published

book first in the West in 1970, having been smuggled out of the

Soviet Union. It was extremely rare for a Soviet writer to dare

to attack the Gulag system openly until Gorbachev's time in the

mid-1980s.] "Underground Rivers Flow To The Sea" was

the only novel ever published about exile in Azerbaijan during

the Soviet period.

Amazing Mother

The author named his protagonist Samira Aydin. In other words,

though he didn't use my mother's name exactly, he retained her

initials - SA - Samaya Aghayeva.

Left: Naila's daughter Samira with her grandfather Anvar.

Samira was given the pseudonym that her grandmother is called

in Mehdi Husein's novel "Underground Rivers Flow Into the

Sea" by 1983. Left: Naila's daughter Samira with her grandfather Anvar.

Samira was given the pseudonym that her grandmother is called

in Mehdi Husein's novel "Underground Rivers Flow Into the

Sea" by 1983.

When my daughter was

born, I named her Samira - Mehdi Husein's name for my mother.

Neither my father or my stepfather would give me permission to

call my daughter by mother's real name as it brought back such

difficult memories, only reminding them that she was not with

us anymore.

But years passed and my sister did name her granddaughter Samaya

after mother. We really wanted so much to keep the name of our

mother in our family.

Mother was such a great woman - intelligent, calm, and very kind.

She had so many friends.

Actually, when I was growing up, my mother treated me more like

a girlfriend. We used to solve our problems together. Even when

mother decided to get married overnight to save us from going

to Kazakhstan, she talked to me about her dilemma, asking my

opinion. I was only 11 years old at the time. My mother always

trusted us.

Trust is such a fundamental thing and I, in turn, trust my children.Mother

always worked a lot. She held down two, three jobs. She became

the Deputy Director of a chemical laboratory. Actually, she was

the first chemist to earn her candidate of sciences degree.

I learned many things from childhood. When I was five years old,

I had to take care of my sister while my mother was at work.

I would take my three-year-old sister to kindergarten, while

I was going there myself.

My mother was a small woman but she had a strong character. She

did everything for us. Even today, we hold her up as model for

us.

Whatever major decision we have faced in life, we would always

think whether it would make our mother happy or not. Even now

when I do something, I always think whether my mother would approve

of it or not.

If this tragedy had not happened to our family, everything would

have been so different now. My mother and father loved each other

more than anything else. They had a deep friendship. Everyone

knew my mother and father loved each other. They both were so

talented. Our life would be happier. And the most important thing,

I don't think that my mother would have died so young.

I always tell these stories to my grandchildren. I want them

to know who their grandmother was. We - the daughters of Samaya

- always aspire to be like her. I want my children and grandchildren

to be like her.

I always tell them that whenever they think of doing something

bad remember: "You are the grandchildren of Samaya."

This is the greatest legacy that she could ever have given us

- the model of her life, even under incredible duress.

Naila Hasanova graduated from the Physics faculty of Baku State

University and she teaches physics as a Senior Lecturer in the

Physics Department of the Azerbaijan Oil Academy. Her daughter

Nargiz Rizazadeh and sister Elmira also contributed to this article.

Back to Index AI 14.1 (Spring

2006)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|