|

Spring

2000 (8.1)

Pages

50-53

Mirza Fatali

Akhundov

Alphabet

Reformer Before His Time

by

Farid Alakbarov

The Manuscript Institute

has a special section in its archives dedicated to the work of

Mirza Fatali Akhundov (1812-1878), including both published and

unpublished manuscripts. Though Akhundov is mostly remembered

for his founding work in theater and drama, his contribution

to alphabet reform was enormous. The Manuscript Institute

has a special section in its archives dedicated to the work of

Mirza Fatali Akhundov (1812-1878), including both published and

unpublished manuscripts. Though Akhundov is mostly remembered

for his founding work in theater and drama, his contribution

to alphabet reform was enormous.

Akhundov worked as an interpreter in Tiflis (Tbilisi, Georgia)

and began his work regarding alphabet reform in 1850. His first

efforts focused on modifying the Arabic script so that it would

more adequately satisfy the phonetic requirements of the Azeri

language. First, he insisted that each sound be represented by

a separate symbol - no duplications or omissions. The Arabic

script expresses only three vowel sounds, whereas Azeri needs

to identify nine vowels.

Photo: Bust of Mirza Fatali

Akhundov, inside the library that bears his name in Baku.

Second, he hoped to rid the script of diacritical marks such

as "dots and loops," which he felt slowed down the

handwriting process. Third, he felt that literacy would be facilitated

if the script were written in a continuous fashion with no breaks

in words. This would enable people to more readily discern where

words began and ended.

In 1863, Akhundov went to Istanbul and personally presented his

ideas to the Scientific Society of Osmanlis. His proposals triggered

serious debates in the Turkish newspapers. A number of publishers

and intellectuals were against this reform. However, poet Namik

Kamal strongly defended his efforts.

Hot debates ensued and

were amplified by those who sought to purify Turkic languages

and purge all Arabic and Persian words from the Turkic vocabulary.

In the end, conservative forces won out, not only in Azerbaijan,

but in Turkey as well. The greatest resistance came from those

who believed that since the Koran was written in the Arabic script,

it is holy and should not be tampered with. Akhundov finally

realized that it would be impossible to carry out even negligible

reforms in regard to the Arabic alphabet. Archival materials

at the Institute show that Iran strongly opposed this project,

according to views set forth by the Iranian Ambassador to Turkey. Hot debates ensued and

were amplified by those who sought to purify Turkic languages

and purge all Arabic and Persian words from the Turkic vocabulary.

In the end, conservative forces won out, not only in Azerbaijan,

but in Turkey as well. The greatest resistance came from those

who believed that since the Koran was written in the Arabic script,

it is holy and should not be tampered with. Akhundov finally

realized that it would be impossible to carry out even negligible

reforms in regard to the Arabic alphabet. Archival materials

at the Institute show that Iran strongly opposed this project,

according to views set forth by the Iranian Ambassador to Turkey.

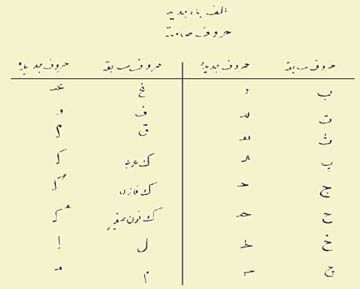

Photo: Columns in order: the

second version of Azerbaijan's Latin alphabet (after 1928), the

pre-reform Azeri Arabic script and Akhundov's proposed Latin

script.

By 1878, Akhundov had given up on trying to reform the Arabic

script and was refocusing his attention on introducing a Latin-modified

alphabet with a few Cyrillic characters. "Whoever wants

to use the traditional Arabic script may use it, others can opt

for the new alphabet," Akhundov would say. Nevertheless,

despite the fact that he included a few Cyrillic characters in

the proposed script, the Russian government did not lend any

support to his efforts. And again, this project failed.

Nevertheless, he managed to bring these issues into the public

arena, and some intellectuals began discussing it in the media.

In 1886, seven years after Akhundov's death, the newspaper "Caucasus"

published an article by Mirza Alimammad calling for a change

of the Arabic script. In 1898, several issues of the same paper

published a lengthy article by Firudin bey Kocharli entitled,

"The Arabic Alphabet and its Shortcomings."

Jalil Mammadguluzade, editor of the famous publication "Molla

Nasraddin" (1906-1931), commented on the Arabic script and

the need for reform: "It is necessary to substitute these

hieroglyphs with the Latin script."

Nariman Narimanov, an active member of the government in the

early part of the century, also criticized the Arabic script.

Narimanov's solution was to accept Cyrillic, as he had written

some of his novels in a modified script he had created to express

the peculiarities of Azeri phonology.

Akhundov was clearly a visionary whose ideas would follow only

half a century later.

Azerbaijan officially adopted a Latin-modified alphabet on October

20, 1923. At the beginning, both Arabic and Latin were allowed

to jockey for popular use. But by January 1st, 1929, the atheist

government of the Soviet Union banned the use of the Arabic alphabet

in Azerbaijan. Enormous book-burning campaigns were carried out

to obliterate the memory of this script.

Photo: The 1857 version of

Akhundov's proposed reformed Arabic-based script. Photo: The 1857 version of

Akhundov's proposed reformed Arabic-based script.

Charts courtesy of "Schriftreform und Schriftwechsel bei

den Muslimischen Russland- und Sowjetturken" by Ingeborg

Baldauf (Akademiai Kiado, 1993).

Five years after Azerbaijan introduced the Latin script, Turkey

reached the same decision in November 1928. The law went into

effect on January 1, 1929.

But Turkey's decision to opt for an alphabet that was readable

by Soviet Turkic nations was troublesome for Stalin, who feared

that they would unite together against his authority. He hadn't

expected Turkey to adopt Latin as well. Therefore, ten years

later in 1939, Stalin moved swiftly to undermine such efforts

and quickly imposed widespread use of Cyrillic in all Islamic

regions of the Soviet Union.

Akhundov would no doubt have smiled had he known that one of

the first significant legislative acts of the Parliament of the

newly independent Azerbaijan Republic was the re-adoption of

the Latin alphabet. The decision came only a few short weeks

after independence, on December 25, 1991. Akhundov's legacy lives

on.

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.1) Spring 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index AI 8.1 (Spring

2000)

AI Home |

Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|