|

Spring

2000 (8.1)

Pages

68-69

Changes in Azerbaijan's

Educational Landscape

by Isgandar

Isgandarov, Deputy Minister of Education

So much has changed

during the last decade in regard to alphabet and language usage

in our country. So much has changed

during the last decade in regard to alphabet and language usage

in our country.

Left: More and more parents

are sending their children to Azeri-track schools rather than

Russian-track schools because they want them to be fully versed

in their native language. But the lack of Azeri-language textbooks

is a serious problem.

One of the first

laws passed by Azerbaijan's Parliament after the collapse of

the Soviet Union, when our country gained its independence, was

the adoption of the Latin script to replace Cyrillic, which had

been imposed on us in 1939 by the Communist regime.

In fact, this event somehow put an end to the unprecedented "experiment"

of changing the alphabet, which has occurred four times during

the 20th century, primarily on the initiative of the Soviet government.

But at a much deeper level than alphabet usage are the perceptions

and attitudes towards national language that are changing. Though

Azeri used to be "on the books" as one of our national

languages during the latter years of Soviet rule, still Russian

was much more dominant, especially among the individuals who

held the highest professional positions. Only those who mastered

Russian attained those ranks in government, science, medicine

and academic life.

Soviet government and

Communist ideology directed its power to the propaganda and development

of the Russian language. National languages, including Azeri,

were not allowed to enter the orbit of the Russian language. Soviet government and

Communist ideology directed its power to the propaganda and development

of the Russian language. National languages, including Azeri,

were not allowed to enter the orbit of the Russian language.

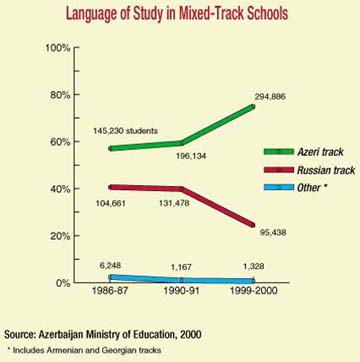

Left: During the Soviet period,

a two-track system (Azeri vs. the more prestigious Russian) became

widespread. Today the goal is to strengthen Azeri instruction

to equal the Russian education.

Today, now that Azerbaijan is independent and its Constitution

declares that Azeri - and only Azeri - is our State language,

public attitudes are gradually changing. Azeri is becoming a

more important factor in our socio-political life. Of course,

all these transitions that are occurring in the usage of our

alphabet and language have deep ramifications for educators.

For example, publishing educational books has become one of our

biggest problems. It's a topic that demands much attention and

planning. We are carrying out serious work in this field.

Pressure to Use

Russian

During the Soviet period, I used to work as an inspector in the

Sumgayit Department of Education. At that time, the Russian language

prevailed over Azeri, even in everyday situations. Even people

who couldn't really speak Russian were trying to use it. You

sensed it all the time - in government offices, on the street,

waiting for elevators, in stores, everywhere. All documents,

meetings and conferences were held in Russian. If someone couldn't

speak Russian at a Communist Party meeting, he was never given

the floor, no matter how brilliant or worthy his ideas were.

This is a historical reality. It's a sad remembrance of the recent

past.

I remember that when

I had to give speeches at Party meetings, I used to prepare my

reports in Azeri. But I was never allowed to make any speech

in Azeri, so someone was assigned to translate for me. Even though

I spoke Russian with a heavy accent and wasn't nearly as fluent

in Russian as in Azeri, I was required to use Russian. I'm sure

that if Russian had prevailed after we gained our independence

and the emphasis had not shifted to Azeri, I would never have

been appointed as Deputy Minister of Education. I remember that when

I had to give speeches at Party meetings, I used to prepare my

reports in Azeri. But I was never allowed to make any speech

in Azeri, so someone was assigned to translate for me. Even though

I spoke Russian with a heavy accent and wasn't nearly as fluent

in Russian as in Azeri, I was required to use Russian. I'm sure

that if Russian had prevailed after we gained our independence

and the emphasis had not shifted to Azeri, I would never have

been appointed as Deputy Minister of Education.

I remember how parents used to ask me to recommend a good Russian

school for their children. Sometimes they themselves didn't even

speak Russian. Nevertheless, it was only natural that families

wanted to send their children to Russian schools - they wanted

the best for their children's future. Let's be frank. In many

cases, education in Russian language schools was superior. First

of all they had more textbooks and the quality was better. Even

pre-school and kindergarten classes were better.

Of course, the Azeri

language was taught even at the Russian schools, but mostly on

a formal level, not at a very profound level. In fact, the Ministry

of Education itself stated that failure to pass exams in Azeri

would not be held against students, as the study of Azeri in

Russian-track schools was voluntary. Some Azerbaijanis didn't

even bother to take those classes; some even protested that such

classes were being offered. Of course, the Azeri

language was taught even at the Russian schools, but mostly on

a formal level, not at a very profound level. In fact, the Ministry

of Education itself stated that failure to pass exams in Azeri

would not be held against students, as the study of Azeri in

Russian-track schools was voluntary. Some Azerbaijanis didn't

even bother to take those classes; some even protested that such

classes were being offered.

I was educated in Azeri as were all four of my children. Even

though they went to school in the 1970s, when Russian was at

its most dominant, I sent them to Azeri schools. I respect the

Russian nation and language. But I think that if someone does

not love and understand his native culture, he cannot value other

cultures. As the educator Ushinski once said: "If a child

has not learned his native language by the time he is 11 or 12

years old, it will be difficult for him to learn foreign languages

later on."

Azeri Language Azeri Language

Today the attitude towards Azeri has changed considerably. Of

course, Azeri has had official status as a State language since

1978 (along with Russian), but such prestige was just on paper.

In practical terms, Russian dominated.

After we gained our independence, a new Constitution was drawn

as guidelines for our new independent republic. When it was adopted

in November 1995 by a general referendum, the role of Azeri increased

substantially. Now the language is used everywhere at the official

level - socio-economical, cultural and political. It's required.

At State organizations, all correspondence and meetings are conducted

in Azeri, even though many of the decision-makers know Russian

better than Azeri.

The Azeri language has also become the language of instruction

in our schools. President Aliyev himself has emphasized the role

of Azeri several times in his speeches. When people don't speak

Azeri at high-level meetings, he openly criticizes them. The

President has told us several times: "We want our children

to be able to read Shakespeare in English, Pushkin in Russian

as well as some of the other world literature and scientific

works in their original languages. But at the same time, they

need to be able to read our own Azerbaijani poets, Nizami, Fuzuli

and Nasimi in Azeri. It's essential that we teach our children

correct and beautiful Azeri. Every Azerbaijani must be fluent

in the Azeri language."

Improving Azeri

Schools

The outlook for Azeri schools is improving. Now there are some

very strong Azeri schools, not only in Baku but in remote villages.

For example, Azerbaijani (not Russian) school students took third

place in an international mathematics contest last year. This

year, two pupils from an Azeri school took first place at the

national Mendeleyev Contest in Chemistry. These days the winners

of national school competitions are usually from Azeri schools;

several years ago, the winners usually had studied at Russian

schools. This fact itself shows that the attitude toward our

national language is improving; this process is strengthening

day by day.

Now parents call and ask me to help them find a good Azeri school.

This often surprises me as I would have expected such people

to choose a Russian school - they hold high positions and their

children speak excellent Russian. It looks like they are beginning

to understand how to value the historical reality and possibility

of national progress and prosperity through the use of our national

language.

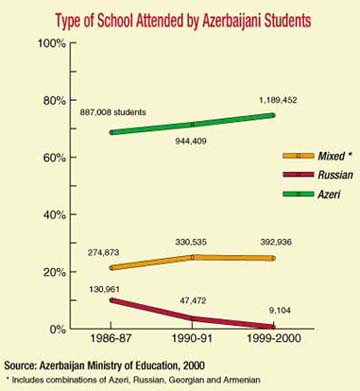

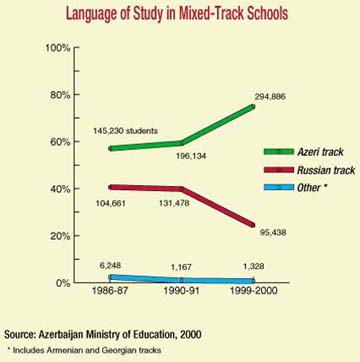

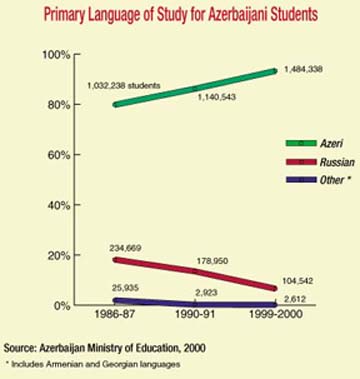

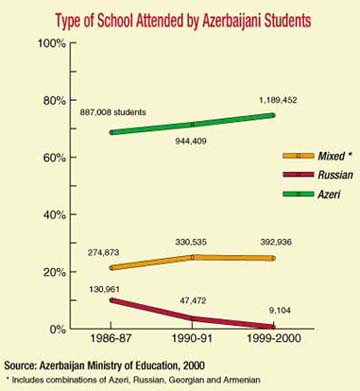

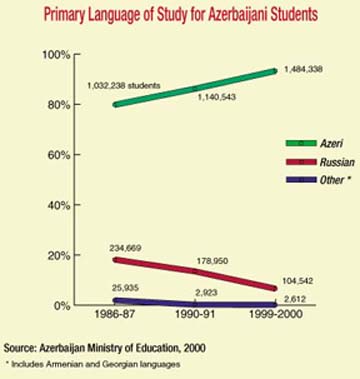

Statistics also support this trend. In 1990-1991, out of 1,322,416

students, 14 to 15 percent of them were in non-Azeri tracks including

Russian, Armenian and Georgian. Today the figure has dropped

to 6 percent. This doesn't mean that there has been pressure

to transfer from Russian to Azeri schools. It has taken place

naturally. First of all, the ratio between Azeri speakers and

Russian speakers is changing in favor of Azeri. Second, Azerbaijanis

have come to realize the importance of Azeri in the political,

social and cultural life of the country. A patriotic attitude

toward the national language is being formed.

Strengthening Education

Our school programs and curricula are also improving, but it's

not an easy process. The curriculum still needs to be updated.

Literature textbooks need to include a greater selection of our

own authors. Right now, some of Azerbaijan's most important writers

who created their works during the Soviet period are totally

being neglected and ignored. Each literary work and writer must

be valued according to the period in which it was created - not

according to today's standards.

The method of teaching languages also needs to be changed. Have

we learned foreign languages like Russian or English from what

we studied at school? Not really. It's the same with Azeri. I

think we need to adopt new teaching methods, especially in language

learning. We need to take advantage of international experience

and teaching techniques. At the Ministry, we've already allotted

more hours for teaching Azeri, and now we require an Azeri exam

for Russian schools.

One of the important factors is that the new educational program

requires the teaching of Azeri on the level of State language

in non-Azeri track schools (Russian and Georgian).

Knowledge of Azeri is the key to learning and understanding our

own literature and our own mentality. Right now, Russian-track

students do not even know the works of such valuable writers

as Nizami, Fuzuli and Sabir because the Russian school curriculum

did not include intensive study of Azerbaijani literature. Our

goal is to create the same curriculum for Azeri schools and Russian

schools.

Of course, we can't expect to see sweeping changes overnight.

We have much to learn and we must be open to new ideas. At the

same time, we shouldn't blame our young people for not knowing

Azeri - it's not their fault. There are many young people who

don't know Azeri but are still patriotic and valuable for building

Azerbaijan's future. These young people comprise what we might

call our "golden fund."

I've always had deep confidence in the future of this nation.

I knew that Azeri would eventually gain its rightful place in

our culture. I was optimistic because I knew that no empire can

last forever, nor can it sustain itself, even for a long time.

People who are far from their native culture and tradition will

never be successful in building a nation. I'm not saying, "Don't

learn other languages." By all means, learn as many languages

as possible - but first of all, learn your own. As the great

educator Firudin bey Kocharli once said, "The mother tongue

is of moral value to the nation." May we always protect

and esteem this value. It is our moral duty.

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.1) Spring 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index AI 8.1 (Spring

2000)

AI Home |

Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|