|

Spring

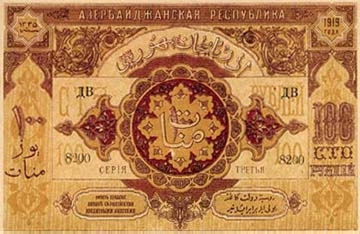

2000 (8.1) Learning to

Read All Over Again

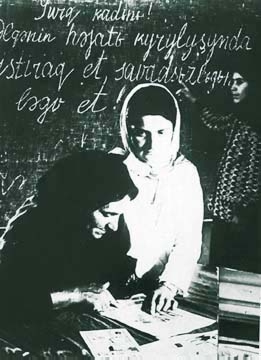

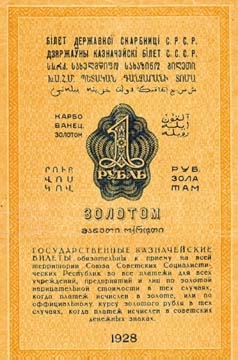

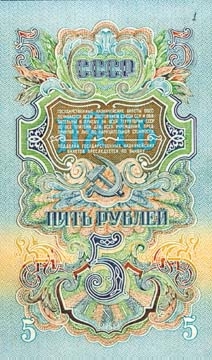

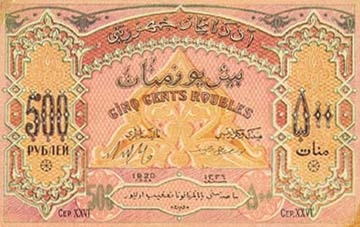

Today, this palatial building functions as Baku's major "Wedding Palace". Although the Club was quite a distance from our house, Mom rarely missed class. Soon she was reading fluently. I remember that her favorite novels included Victor Hugo's "Les Misérables" and Rashad Nuri Guntekin's "Chaligushu" (The Wren). Photos below: Currency used in Soviet Azerbaijan during various time periods, reflecting the changes in scripts from Azeri Arabic to Azeri Latin, early 20th century. Courtesy: Yagub Karimov.  The Soviet campaign against women wearing the chador [veil] was organized hand-in-hand with the literacy campaign. The process itself was called "Doloy Chadra!" In Russian "doloy" means "down with", as in, "Down with Chadors!" or "Off with Chadors!" Newspaper articles and banners published slogans discouraging "progressive" women of the Soviet Union from being "backward" and wearing veils. Of course, without a veil it was difficult for them to practice being devout Moslems. But women throughout Azerbaijan, for the most part, embraced the idea and shed their chadors as if they had been waiting to do so for a long time. Jafar Jabbarli's play "Sevil", staged in 1928, depicted its heroine as taking control of her own destiny and taking off her veil. Many women attended the theater that season. Many are said to have left the theater no longer wearing veils - they had courageously decided to take them off. The process of shedding the chador extended over a period of about seven to eight years. You have to remember that prior to this period, Baku was a city where no woman went out on the street unescorted. So changing the dress code was a major decision.  Alphabet Changes The new Latin script was soon viewed as a threat to the sovereignty of the Soviet government. Of course, Azerbaijanis had been considering adopting a modified Latin alphabet long before it became official.  Stalin seems not to have anticipated that Turkey would give up the Arabic script. Since the majority of nations gathered under the Soviet umbrella were of Turkic origin, he soon feared that the alphabet might become a consolidating factor to unify these nationalities against him. As fate would have it, those who showed the most enthusiasm for universal acceptance of Latin at Baku's Congress became victims of Stalin's repression starting in 1937. They were among the first to be arrested, sent off to exile or executed. Their crime: "Pan-Turkism".  So in 1940, Stalin made it mandatory for all the Turkic republics of the Soviet Union to adopt Cyrillic. Georgia and Armenia, however, were allowed to keep their original alphabet. Stalin was a Georgian, and one of his closest advisors - Mikoyan - was Armenian.  I have to confess that to me the Cyrillic alphabet is one of the ugliest and least practical alphabets. Look at its letters. So many of them are alike ("sh," "i", "m", "t") and when they follow sequentially, it's hard to figure out the word. Changing the alphabet again - this time to Cyrillic - brought major confusion, not just to the children studying in schools. It was done to sabotage and undermine the Turkic republics. Millions of people simply could not read the new alphabet. It's not easy for a middle-aged person who is used to one alphabet to have to start all over and learn a new one. That's exactly the same situation that we face today, now that the alphabet has been changed back to Latin. It takes time. You can't just change an alphabet overnight. Of course, these days, economic factors have compounded the problems of introducing a new alphabet. We're going through a major transitional period. It's not that we didn't have economic difficulties during the Soviet period. It was a lie that people were living happily without a single care under the Soviet regime. I remember my father holding down three or four jobs just to earn enough money. Each time the alphabet changed, part of our literary heritage was lost. When we adopted Latin the first time, the literary heritage of Arabic was lost. With the introduction of Cyrillic, the heritage of Latin was lost, even though it was only official for about ten years. And now again, it won't be long before books that have been published in Cyrillic will no longer be read either. This is one of the problems that we'll have to deal with. All of my books as a literary critic have been published in Cyrillic. Within five years or so, the younger generation won't be able to read my books. Sometimes I think: "What a pity! I've been serving this society as a scholar for 55 years. But none of my books will even be readable in the future." These days, kids know both alphabets - Cyrillic and Latin. But within five years' time, that won't be the case. I'm still convinced, however, that we made the right decision to embrace Latin. Our future is the main issue. I'm among the happiest people in the world because I've seen the collapse of the Soviet Union with my own eyes. Of course, it's difficult to get used to things like a market economy and new trends in society. But I am no longer a slave. I'm my own master. Now I can breathe freely. I have a photo of my parents with tears welling up in their eyes while they were listening to the announcement of Stalin's death [1953] on the radio. But I was glad when that day came, even though I'm a sympathetic person by nature. Return to Latin It's important for us to adopt the Latin alphabet. A common alphabet will bring us together with the other Turkic peoples. It will give us a national identity. It will let us integrate into the larger international community more easily. The Latin alphabet will lead us in the direction that we want to go in history. The Cyrillic alphabet was imposed on us by Soviet totalitarianism, and we needed to get rid of it. Some people in the government are still against Latin. Some of them seem to be waiting for the day when the policy will be reversed, and Cyrillic will reign again. Frankly speaking, I think that's one of the main reasons why the process of adopting our new alphabet has been so slow. As for me, I'm comfortable with all of the scripts. During childhood I learned the Arabic script from my parents. Then during my early school years, I studied Latin. My scholarly work was published in Cyrillic. Believe it or not, I still use the Arabic script for research, because I deal with Azerbaijan's classic literature. And now we're back to a slightly different version of Latin. So there you have it - four scripts - and all within my very own lifetime. Footnote: Kamal Talibzade, one of Azerbaijan's

more famous literary critics, was interviewed by Jala Garibova.

His article, "Transitions: Literary Criticism in Azerbaijan

A New Look at Soviet Works," appeared in AI 4:1, Spring

1996. |