|

Autumn 2000 (8.3)

Pages

28-31

Seeds of Change

Transition

in Azerbaijan's Agriculture

by

Arzu Aghayeva

Above:

Summer fruits

at the Taza Bazaar in Baku. Photo: Blair

Agriculture has long been a strong point for Azerbaijan. The

country's mix of rich farmland and a wide range of climatic zones

help support a wide variety of crops. But like other industries,

agriculture is still struggling to cope with the country's new

market economy. Under the Soviet system, Azerbaijan had a built-in

market for its vegetables, fruits, cotton, wool and raw silk,

since they were all sent to the All-Union Fund. In turn, the

Republic received products that it needed, like meat, dairy products

and grain.

Since independence, Azerbaijan has had to find new markets for

its agricultural products as well as new suppliers for the items

it has yet to produce itself. We talked to two experts from Azerbaijan's

Ministry of Agriculture about Soviet planning and today's complex

rebuilding process. Both agree that, despite major obstacles,

there is hope for the future of agriculture, Azerbaijan's second

- most important natural resource.

Private ownership of land ended when the Soviets took over Azerbaijan

in 1920. Farmland was then organized into state-owned agricultural

cooperatives, known as kolkhoz and sovkhoz. Soviet leaders mandated

which crops would be grown and where those crops would be sent

once they were harvested.

It soon became clear what tremendous potential Azerbaijan had

for agriculture, specifically for growing fruits and vegetables.

Lankaran in particular was perfect for planting cabbages, tomatoes,

eggplant and peppers. This region is located close to the southern

border near Iran. "Lankaran was so productive that they

called it 'The All-Union Garden,'" says Samad Garaisayev,

chief expert for Cattle Breeding Management at Azerbaijan's Ministry

of Agriculture.

Vegetables also became

a specialty for kolkhozs and sovkhozs in Guba, Khachmaz and Masalli.

In all, Azerbaijan sent 500,000 to 600,000 tons of vegetables

each year to the All-Union Fund. Vegetables also became

a specialty for kolkhozs and sovkhozs in Guba, Khachmaz and Masalli.

In all, Azerbaijan sent 500,000 to 600,000 tons of vegetables

each year to the All-Union Fund.

"None of the other republics sent as many vegetables to

the Fund," says Sabir Valiyev, head of Cultivation Management

at the Ministry of Agriculture. "Early in April, our cabbages

were already being sold in Moscow and Leningrad, at a cheap price."

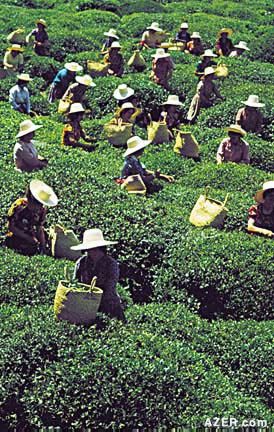

Left: Tea harvesting in the

Lankaran region, which is fairly close to the Iranian border.

Some of the vegetables grown in Azerbaijan were canned before

being sent on to other Soviet republics. These included pickled

cucumber, tomato, cabbage and eggplant as well as various kinds

of jams.

The cotton industry was also very important to Azerbaijan. In

the 1970s and 1980s, the Republic produced about 1 million tons

of cotton a year. However, since prices for cotton have gone

down in the world market, today's production has decreased significantly.

Less Grain, More

Wine

Grain production in Azerbaijan rose substantially during the

Soviet period, reaching more than 1 million tons a year in the

1970s and 80s. Part of this increase had to do with productivity-the

amount of grain harvested per acre more than tripled between

1913 and 1970.

Instead of developing the grain industry further, however, the

Soviets decided to concentrate on Azerbaijan's wine industry.

Grain growing was restricted. At the time, Azerbaijanis still

had enough grain for themselves, since deficits were supplemented

by the All-Union Fund.

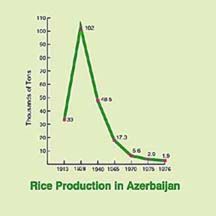

One of the grains that was cut back was rice. Traditionally,

rice had been grown for a long time in Azerbaijan, mostly in

the southern regions of Masalli and Lankaran and also in Shaki,

in the northern region of Azerbaijan in the foothills of the

Caucasus mountains. The Soviet leaders reasoned that since plenty

of rice was being grown in other republics of the USSR, there

was no need to grow it in Azerbaijan.

In the 1970s, the Communist Party and the Cabinet of Ministers

issued special decrees for developing Azerbaijan's agriculture,

especially in terms of growing grapes for wine. Funds were allotted

for new railroads and water pipelines, and 70,000 to 80,000 hectares

of land were set aside for vineyards. The plan was for Azerbaijan

to produce 3 million tons of grapes per year by 1990. By 1982

Azerbaijan was already producing 2.1 million tons of grapes,

not so much by expanding its acreage, but by increasing productivity.

Planned Economy Planned Economy

Left: Selling melons out of

the trunk of a car - a typical scene. In Lankaran. Photo: Blair

"During the Soviet period, we developed the branches of

agriculture that Moscow considered necessary: cotton-growing,

vine-growing, vegetable-growing," says Garaisayev. "But

too few of those crops were kept in Azerbaijan. For instance,

we sent cotton to Russia, which they used to process and produce

cloth. Of course, it enabled them to take all the profit."

"Moscow always wanted Azerbaijan to be dependent,"

he continues, "in cattle breeding as well as in other things.

Each year, Azerbaijan received an average of 1,200,000 tons of

milk and dairy products and about 35,000-40,000 tons of meat

and meat products from the All-Union Fund. We couldn't breed

our own cattle because we weren't allowed to grow the proper

feed for them. With the so-called 'planned economy' excuse, Moscow

hampered our cattle breeding."

As a result, Azerbaijanis consumed much less meat and dairy products

than people in other Soviet republics. For example, if an average

person in the USSR ate 65 kg of meat each year, for an Azerbaijani

it was closer to 37 kg.

Privatization

After Azerbaijan gained its independence, Parliament adopted

a new law facilitating the privatization of property in 1996.

Farmland was apportioned as personal property. Of all the CIS

countries, Azerbaijan has been the only one to use such a method.

In Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and other former Republics, the land

is rented or leased for temporary use.

Tractors and other equipment were given to groups of farmers

based on a property - share arrangement; for example, one tractor

was designated for every 10 farmers. If a farmer doesn't have

access to a tractor, they can contract with those who do.As of

1996, nearly all farm animals were divided among the private

sector as well - 99.8% of the cattle and 98% of the sheep. The

remaining cattle and sheep are held by the government for breeding

purposes.

Above:

The Soviet

collective farm, known as a kolkhoz, found in the Ivanovka village

in the Ismayilli region in central Azerbaijan. This kolkhoz is

operated by Malakan Russians and during the Soviet period was

a model project because of its high production. Photo: Litvin

For each crop, it's up to the farmers to sell their own produce,

whether it's tomatoes, cucumbers, watermelon, berries or grapes.

The prices are set by the market demand, not by the government.

Farmers can sell their produce to other countries as well. Most

of it goes to the Russian cities of Volgograd and Astrakhan,

especially dates, tomatoes, cucumbers and watermelon. Hundreds

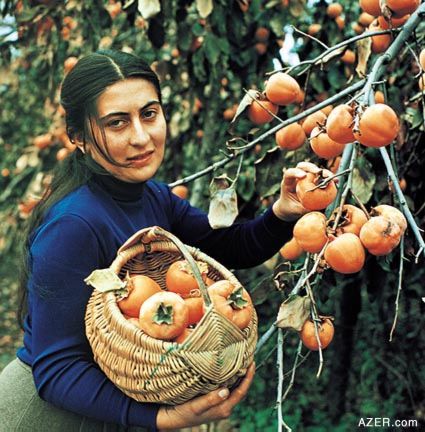

of tons of persimmons are grown each year in Shaki, Zagatala,

Ganja, Gazakh, Tovuz, Goychay and Aghdash.

Finding New Markets

Fruit ranks near the top of the list of Azerbaijani exports.

Azerbaijan produces 400,000 to 450,000 tons of fruit a year.

The region of Guba, for instance, is famous for its apples, especially

a sweet red variety called "Jir Haji". When other kinds

of apples were brought from abroad and grown in Azerbaijan, they

weren't as attractive or as resistant to disease. Another local

apple variety is called "Gizil Ahmad". This apple grows

mostly in Gabala, Oghuz and Ismayilli, in the mountainous places.

Processed fruit also has potential. "Last year we participated

in the Royal Agricultural Exhibition held each year in London,"

says Valiyev. "We took our jams and juice, such as fig jam,

berry jam and walnut jam. Representatives from 70 countries participated

in that exhibition. They were delighted with the taste of our

jams."

Because the Soviets had placed so much emphasis on Azerbaijan's

wine industry, it is still fairly viable. During the 1970s and

80s, Azerbaijani wines were sold in Moscow, Belarus, Estonia

and the Baltic. Table wines such as "Giz Galasi", "Yeddi

Gozal", "Gara Gila" and "Naznazi" are

made from the "Madrasa" pink grape, exclusive to Azerbaijan

and indigenous to Madrasa, a village in Shamakhi, a few hours

north of Baku.

"We participate in many international tasting committees

and international exhibitions," says Valiyev. "Lately

our wines have been receiving numerous gold medals. This year

our brandies won a gold medal at an International Tasting Convention

held in the U.S. We also participated in an international exhibition

held in Belgium. Five of our products won gold medals in an anonymous

taste competition among 156 countries: our champagnes and 'Golden'

vodka."

Left: The produce section of Ramstore, the

first major supermarket to come to Baku in 1997. Photo: Blair Left: The produce section of Ramstore, the

first major supermarket to come to Baku in 1997. Photo: Blair

Self-Sufficiency

Crops that had been decreased during the Soviet period are gaining

ground once again. "We currently import rice from Iran,

Brazil and China," Valiyev says, "but now we are starting

to plant rice in Azerbaijan again. If in 1999 we planted rice

on 3,629 hectares, in 2000 we planted it on 4,437 hectares. We

hope that in the future Azerbaijan will be self-sufficient in

terms of its rice supply."

"After the collapse of the Soviet Union, we started growing

more grain, but it's still not enough," says Garaisayev.

"Azerbaijan currently produces 1.5 million tons of grain

per year-all for its own use - but it needs 2.5 million tons.

These days there is a tendency to replace vineyards with wheat

fields."

Another crop that is making a comeback is sugar beets. "Azerbaijan

used to grow sugar beets prior to the Soviet period," Valiyev

says.

"But when the Ukraine started cultivating the crop, there

was no longer any need to grow it, as they provided all of the

USSR's sugar. After we gained our independence, we started planting

sugar beets again in Nakhchivan, Beylagan, Sabirabad, Imishli

and Salyan. Today Azerbaijan plants about 50,000 to 60,000 tons

of sugar beets per year. But there are no sugar processing factories.

The beets have to be sent to Iran (Ardabil), across the border

from Bilasuvar (Azerbaijan). Iran processes the sugar beets and

returns the product to us. That makes the sugar too expensive

for our own consumers. We need to build our own factory in Azerbaijan."

One of the more profitable trends has been toward cattle farming.

"You can see that now we have a lot of meat and dairy products,"

says Garaisayev. "This comes from the private production

of our farmers. After privatization in 1996, cattle breeding

increased. Now people make money from this industry."

Valiyev notes that the quality of dairy products has also improved.

"Now our Azerbaijani companies are producing about 15 kinds

of dairy products: yogurt, cheese, cottage cheese and milk. You

can even see in the stores that our local dairy produce is outselling

foreign products."

New Challenges

Privatization of factories is still a major hurdle in the development

of agriculture in Azerbaijan. Production and processing are interdependent,

Valiyev says. "Producers need someone who will buy all of

their produce. They sell their produce in the market while it's

still fresh. But what can they do with the rest of it before

it spoils?"

Above: The persimmon is

a major crop in Azerbaijan. Photo: Huseinzade

Presently, only a few factories have been privatized and are

operating. Factories in Guba and Saatli produce small packages

of juice and various kinds of jam. Another factory in Lankaran

produces tomato paste. These three new factories export their

produce to various countries, such as Japan, Russia, Belgium

and Switzerland.

Tea processing factories also need to be privatized. Azerbaijan

used to produce 34,000 tons of tea a year in the 1970s; last

year, the harvest was only 1,900 tons. Part of the problem is

that there aren't any tea processing factories operating. Now

that the tea factories in Baku have been bought by a Turkish

company, farmers are starting to grow tea again. The Azerbaijani

tea is then mixed with other blends of tea from Turkey and India

before being sold.

Azerbaijan has suffered immensely because of the Nagorno-Karabakh

war. Today nearly 20 percent of our land is occupied by Armenians.

A great deal of it was valuable farmland. For instance, in the

Fuzuli region, we used to produce about 100,000 tons of grapes

per year; Zangilan had three grape processing factories with

3,000 hectares cultivated in vineyards. Aghdam was known for

its cotton, and Gubadli for its cattle. When Azerbaijanis fled

from their homes in these occupied territories, they had to leave

an estimated 145,000 cattle behind.

For many growers and

producers, the problem is also a lack of cash-flow. "What

troubles us most these days is that we don't have a credit-union

system that allows farmers to borrow money," says Valiyev.

"Our Ministry wants to establish these credit unions in

every village. That way, when a landowner or a producer needs

funds, he can borrow from the credit union and purchase what

he needs. As soon as these credit unions are established, many

of our problems will be solved." For many growers and

producers, the problem is also a lack of cash-flow. "What

troubles us most these days is that we don't have a credit-union

system that allows farmers to borrow money," says Valiyev.

"Our Ministry wants to establish these credit unions in

every village. That way, when a landowner or a producer needs

funds, he can borrow from the credit union and purchase what

he needs. As soon as these credit unions are established, many

of our problems will be solved."

Left:

Rice production

in Azerbaijan fell dramatically during the Soviet period, as

rice was replaced by other crops.

If Azerbaijan can overcome these obstacles, prospects look good

for the future of agriculture in the country. "Our climate

and soil enable us to grow premium quality produce," says

Valiyev. "Now that privatization has begun, we'll soon witness

a rise in production."

"Now we are living in a transition period," says Garaisayev,

"but we have great plans for the future. Agriculture has

great potential in our country."

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.3) Autumn 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 8.3 (Autumn 2000)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|