|

Autumn 2000 (8.3)

Pages

24-27

Forgotten Foods

A Comparative

Outlook on The Cuisines of Northern and Southern Azerbaijan

by

Pirouz Khanlou

For article translated into Ukrainian by Alexander

http://stroitelstvovrossii.ru/artikle/95-foods.html

Above:

Famous Tabrizi

kufta (meatball) with herbs such as tarragon, chives, cilantro,

mashed yellow peas, rice and a variety of spices. The stuffing

inside is composed o f dried fruits such as sour cherries, prunes,

walnuts and almonds mixed with fried onion and a hard-boiled

egg. A kufta can be large enough to have a whole chicken stuffed

inside. The bread, sangak, is torn into pieces, soaked in the

kufta broth and eaten with turshu (relishes), Prepared by Pari

Abadi, Tabriz, specifically for Azerbaijan International. Photo:

Khanlou

Psychologists have long been fascinated with the problem of whether

it is heredity or rather environment that plays the greater role

in the development of the human species. Numerous studies have

focused on identical twins who were separated at birth and grew

up under different circumstances. In a sense, Azerbaijanis are

like that. Figuratively speaking, they've been separated from

their identical twin and brought up under entirely different

policies and circumstances, which have influenced their social,

political, economic and religious outlook and upbringing. These

differences, in turn, have even impacted the food they eat.

At the beginning of the 19th century, Azerbaijan was one territory

comprised of khanates and ruled locally under the jurisdiction

of the Persian Empire (known at the time as the Union of Gajar

States). Conflict broke out between Czarist Russia and Persia.

Two wars followed upon each other in short succession. Persia

was defeated and forced to cede considerable territory to Russia

in treaties signed at Gulistan (1813) and Turkmanchai (1828).

The territories now known as Georgia, Armenia and Nakhchivan

(an autonomous political region inside Azerbaijan) had to be

surrendered to Russia. Azerbaijan fared even worse because its

territory was split between both Russia and Persia. The Araz

River became the line of demarcation between what is known today

as Northern Azerbaijan (now the Republic) and Southern Azerbaijan,

which is in Iran.

Today, the greater population of Azerbaijanis lives in Iran:

only 8 million reside in the Republic, which gained its independence

from the Soviet Union in 1991. An estimated 25-30 million Azerbaijanis

live in Iran.

Nearly 200 years after being separated, these different "upbringings"

have led the "Azerbaijani twins" down the path to different

destinies and different realities - differences that we discovered

were reflected even in contemporary cuisine and eating habits.

Here Pirouz Khanlou suggests some of the major differences.

_______

When the Bolsheviks captured Baku in April 1920 and began establishing

what would become the Soviet Union, a political course was set

in Northern Azerbaijan that would forever impact every aspect

of life-social, cultural, economic and religious. In fact, the

changes had such a profound effect that they even impacted the

traditional cuisine that had emerged over thousands of years.

The Soviet Union under Lenin (1917 to 1924) began implementing

a planned economic system to unify the vast territory that made

up the largest country on earth, comprising 15 different countries.

These policies continued under Stalin (1924-1953), who launched

an intensive industrialization program that forced the collectivization

of agriculture. The New Economic Planning (NEP) organized the

agricultural industry systematically. Stalin set out to convert

the pre-revolution indigenous feudal agricultural system into

an industrialized system, mobilizing the country in a very short

period to create a self-sufficient economy with full provision

to feed its masses.

It wasn't long before this new centralized approach impacted

the traditional cuisines of the regions. Azerbaijan was no exception.

Obviously, if a traditional recipe called for major ingredients

that were no longer grown locally or were not accessible elsewhere

in the USSR, it wasn't long before that dish totally disappeared

from the table, and subsequently within a few generations even

became erased from memory.

In other cases, even when the ingredients were readily available,

if the preparation relied upon intensive, individualized manual

labor that could not be converted to mass production in factories,

these foods also disappeared. Such was the case of "sangak"

- a flat, wide, whole wheat sourdough bread, traditionally baked

individually in tandir ovens. One of the major reasons we even

know about these foods today is that they are still prevalent

in Southern Azerbaijan.

In an effort to unify the peoples of the Soviet Union and to

create the generic "Soviet man", there was an overbearing

tendency to impose Russian culture as a model, despite the fact

that Russia was only one of the 15 nations that made up the USSR.

Directives came from Moscow and always bore the mark of Russians.

Crops that were grown - cabbage, wheat, potatoes - essentially

catered to a Russian-based cuisine. Azerbaijani cooks had no

choice but to incorporate this produce into their own recipes,

to such an extent that Russian dishes like stuffed cabbage, borscht,

pork sausages and "Stolichni"

(a mayonnaise-based chicken salad), though once foreign to Azerbaijanis'

taste buds, soon became ordinary, everyday fare.

Rice vs. Potato

One of the most pronounced differences between pre-Revolutionary

cuisine in Northern Azerbaijan is the attitude towards rice and

potato. Rice is not an integral part of the Russian diet, potato

is. And subsequently, today in Northern Azerbaijan, potato is

a much more dominant feature than rice.

Blame it on vegetable cultivation. Russians like cabbage and

use it in borscht and stuffed cabbage rolls.

Although cabbage can be grown under various climactic conditions,

rice is much more restricted and requires a wet, subtropical

climate. Soviets were intrigued with the idea of guaranteeing

fresh cabbage in Moscow markets by early April, even before the

snows had melted. This was possible if they planted and transported

it from the southern climes of Azerbaijan. And thus the rice

and tea plantations located in the Lankaran region of Azerbaijan

near the Iranian border were replaced with cabbage farms. Tea

was imported from India and exchanged for Soviet military hardware.

Rice, which had been so fundamental to Azerbaijani cuisine, became

a rarity and a great number of traditional rice dishes disappeared.

Azerbaijanis became potato and bread-eaters instead, and bread

and dough-based dishes like gutab, khangal and dushbara (dishes

unknown in Southern Azerbaijan cuisine) became the primary source

of carbohydrates.

Rice was relegated to the role of luxury - a dish served only

at weddings and special occasions. But Southern Azerbaijanis,

in contrast, still enjoy rice on a daily basis, just as they

have done for centuries.

Above: Seven-Colored Pilaf

(Haft-Rang Plov) is a dish of long-grain rice decorated with

a variety of ingredients, including julienne-cut pistachios,

almonds, orange peel, potatoes, saffron-flavored fried onion

and zarish (burgundy-colored sour dried berries). Usually this

dish is served with saffron-coated chicken. Since it requires

so much preparation, it is usually served at elaborate parties.

Photo: Khanlou

Fewer Spices

The Soviet government soon took control of all imported goods.

As a result, the variety of spices, which provided the nuance

of flavor in Azerbaijani cuisine, disappeared. Russian cuisine

doesn't require many spices, so the Soviet economic planners

considered them superfluous and non-essential. Tightly guarded

political borders and the state-controlled economic program prohibited

spices from being imported from India or the Middle East. And

so it wasn't long before the spice bazaars, with their exotic

aromas and tantalizing colors, disappeared.

Today, there are no spice bazaars in the Republic and the range

of spices is extremely limited, especially in comparison with

Southern Azerbaijan, which is known for its famous spice bazaars

in the major cities of Tabriz, Urmia, Ardabil and Zanjan. The

Amir Bazaar in Tabriz is especially noteworthy because so many

merchants deal in spices.

Consider saffron, an exceedingly expensive spice derived from

the delicate pistils of saffron flowers that are handpicked.

Saffron provides both flavor and golden orange coloring for rice

pilaf. Soviets may have considered it "bourgeois",

and so it disappeared.

Without these spices, food in Northern Azerbaijan became much

plainer. To this day, seasonings are primarily restricted to

salt, pepper, turmeric and a few other seasonings. In the South,

Azerbaijanis still season their dishes with a wide variety of

spices, including ginger, nutmeg, cinnamon, cardamom, caraway,

and numerous spices and mixtures unknown to the West.

Belief Systems

Many traditional ideas and beliefs have disappeared as well.

One dealt with the categories of "hot" and "cold"

foods - much like the beliefs of Ayurveda in India. These categories

refer to the effect food has on the body, not to the temperature

of the food itself.

If you ask an Azerbaijani in the North about the concept of "hot

and cold", you'll probably just get a blank face. But Azerbaijanis

in Iran still believe in these classifications and are careful

to follow guidelines such as: don't mix hot with hot, or cold

with cold. Hot foods are said to raise the blood pressure, cold

foods, to lower it. Foods categorized as "cold" include

cucumber, eggplant, cabbage, tomatoes, lettuce, yogurt, fish

and rice. Foods in the "hot" category include garlic,

walnuts, grapes, apples, honey, eggs, bread and red meat.

Another belief system, that of traditional medicine, has almost

totally disappeared in the North. Soviets tried to stamp out

the use of traditional medicine based on natural herbs. There

used to be herbal medicine shops called "attar", where

you could treat specific ailments with dried herbal mixtures.

Southern Azerbaijanis still have such shops.

In Hajibeyov's musical comedy of 1913, "O Olmasin, Bu Olsun"

(If Not This One, That One), the main character, Mashadi Ibad,

was one such bazaar merchant. In the 1956 movie version, scenes

of pre-Revolutionary Baku include such shops (See AI 5.3, Autumn

1997; SEARCH at AZER.com).

These days, now that Azerbaijan has gained its independence,

again people are beginning to experiment with treatments derived

from natural herbs but very minimally, as Azerbaijanis are more

used to chemical drugs.

Influence of Alcohol

The introduction of alcohol, specifically vodka, during the Soviet

period has shaped Northern cuisine in profound ways. For example,

take the presentation of food. In the Republic, guests are ushered

into a room where there is a long table covered with many small

plates, all within easy reach of every person. In Southern Azerbaijan,

however, there tends to be only one dish or platter for each

entrée, which is passed around.

Why so many small dishes? Perhaps it can be traced to the influence

of vodka. Traditionally, Azerbaijanis did not drink alcohol except

on rare occasions. In Iran, alcohol is illegal and few people

drink. But Russians are known to be hard drinkers who consider

food an accompaniment to alcohol, and not vice versa.

Russians have a saying: "Tea is not like vodka, which you

can drink a lot of". Russians have a tradition of serving

"zakuska" - appetizers set out on small plates, such

as pickles, salami, sausages, salted herring and mayonnaise-based

salads. Nibbling on such dishes enables a person to sustain drinking

for several hours.

Today, these same food

practices continue in the Republic. This may also explain why

rice is served as the last entree at weddings, long after the

major entrees are finished. Were rice to be introduced earlier,

it could interfere with drinking because the guests would be

too stuffed. Today, these same food

practices continue in the Republic. This may also explain why

rice is served as the last entree at weddings, long after the

major entrees are finished. Were rice to be introduced earlier,

it could interfere with drinking because the guests would be

too stuffed.

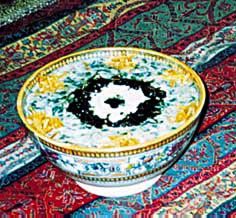

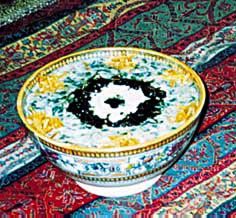

Left:

Gurutli

Ash is a thick, hot vegetable- and herb-based soup mixed with

"gurut", dehyrated yogurt. Garnish with julienne-cut

oinion, crushed dried mint and saffron-flavored fried onion.

Prepared by Tayibeh Karimpour, Tabriz, specifically for Azerbaijan

International. Photo: Khanlou

Curiously, the role of vodka is evidenced in traditional expressions.

When Azerbaijanis describe a difficult task, they say, "I

had to eat a whole sheep to do this." The Russian version

is: "I had to drink half a liter (of vodka)". Azerbaijanis

in the Republic are inclined to offer a lot of toasts when drinking,

a pattern that is barely known in the South. (See "Tamada",

Autumn 1995, AI 4.3; SEARCH at AZER.com).

Mealtime

Another distinct difference relates to mealtimes. In Northern

Azerbaijan, there doesn't seem to be as regular a schedule for

families to eat - no matter which meal. But in Southern Azerbaijan,

fairly routine patterns have been established, and all family

members, including fathers, are usually present - even for the

noon meal.

Perhaps Soviet labor patterns are to blame for practices that

developed in Northern Azerbaijan and are still widespread today.

During the Soviet period, most women were required to work outside

the home. Husbands and wives were often involved in different

sectors, services or factories, which had different time schedules

that did not allow coordination of family mealtimes.

Noon meals were often served in canteens and cafeterias in government

offices and factories. In the Republic today, it is not unusual

for family members to go to the kitchen and find food that has

been prepared earlier and serve themselves.

In the South, the majority of women still do not work outside

the home and thus are able to carry out the more traditional

homemaking tasks related to their families, which could account

for more regular scheduling. Southern Azerbaijanis still break

from work during the hot midday hours. Schools are organized

in shifts "before lunch" and "after lunch",

enabling children to join family members, including their fathers,

for the noon meal.

Entertaining Guests

In the Republic, no matter what time of day or night a guest

arrives, it is assumed that food will be served. There is always

some sort of food available. However, in the South there tends

to be two categories of guests - those who are invited for a

meal such as lunch or dinner, and those who drop in for tea.

Plans are made several days in advance if guests are invited

for meals so that a wide range of dishes can be prepared.

On the other hand, having guests for tea is less formal. An assortment

of sweets will accompany the tea - seasonal fruit, cakes, chocolates,

hard candies or prepared sweets like the deep-fried "zulbia"

and "bamya" dipped in syrup and "Iris", a

chocolate flavored caramel-like candy. "Sharbat", a

fruit-flavored drink, may also be offered.

Religious Festivities

In Iran, two religious months based on the lunar calendar - Ramadan

and Maharram - play a dramatic role in traditions related to

cuisine. Ramadan (known as "ramazan") is the strict

observance of fasting in Islam. People don't eat from sunrise

to sunset - in public, that is. This practice extends even to

drinking water, smoking or chewing gum. However, after sundown,

relatives and close family friends gather in each other's homes

to break their fasts. Tablecloths are lavishly spread with appetizers

and main courses. This practice continues throughout the entire

month of Ramadan and, essentially, ends up being more like a

feast than a fast.

Maharram, the month of mourning, marks the martyrdom of the third

Shiite Imam. This month is characterized by offering charity

to members of the community, especially those who are in need.

Wealthy people arrange large lunches and dinners either at home

or in local mosques. Food is shared with the poor and indigent.

Though both of these religious traditions were widely practiced

by Azerbaijanis, the Soviet takeover in Northern Azerbaijan resulted

in these practices becoming nearly extinct.

Forbidden Foods

Islam places restrictions on a few foods. Those permitted are

known as "halal". Forbidden foods are called "haram"

and include pork, alcoholic drinks, sturgeon and, therefore,

caviar. (Sturgeon falls into the broader category of "fish

with no scales". However, it should be noted that this prized

fish was declared "makruh" by Islamic clergy in 1979

for the first time in the Islamic world. "Makruh" means

that permission has been granted to eat it, though it would be

better not to.)

These religious restrictions continue to impact the cuisine in

South Azerbaijan, whereas during the Soviet period with its secular

and anti-religious sentiments, such restrictions were eradicated

and Northern Azerbaijanis today generally don't observe them.

For example, one of the most prized kababs in the Republic is

sturgeon. Despite the fact that both Iran and Azerbaijan Republic

have access to the Caspian, there are no traditional sturgeon

dishes in the South. White fish is more popular.

Dinner Guests

Even the practice of inviting guests over for dinner differs

between the North and South. For instance, in the South, guests

may be invited to sit on carpets as is the tradition, where a

"sofra" - tablecloth - is spread. But in the Republic

- even in remote villages - guests are always offered chairs

to pull up around a table.

In Iran, when the guests arrive, they are usually ushered into

the living room and offered tea or "sharbat", along

with sweets or fruit. The meal is not yet set out. Later on,

the guests usually move to another room to enjoy the main courses.

The small, cramped apartments that were built during the Soviet

period don't facilitate such hospitality. Most apartments do

not have a formal dining area; the small living room often doubles

as dining room and may even triple as bedroom. When guests arrive,

the food is already set out, with all sorts of small plates of

appetizers spread on the table. All guests immediately take their

places around the table, where they are likely to stay seated

for the duration of the evening.

Obviously, there are numerous other differences that could be

elaborated. But without a doubt the political system imposed

by the Soviet system on Northern Azerbaijan has had a profound,

doubtlessly irreversible, effect on the socio-economic, religious

and cultural developments, including the traditional cuisine.

Pirouz Khanlou, publisher of Azerbaijan

International, is an architect based in California and an amateur

gourmet cook. Marjan and Narges Abadi also contributed to the

research for this article.

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.3) Autumn 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 8.3 (Autumn 2000)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|