|

Autumn 2000 (8.3)

Pages

55-57

The Evil Eye

Staving

Off Harm - With a Visit to the Open Market

by

Jean Patterson and Arzu Aghayeva

Got a headache? Not

quite feeling up to par? Business not going too well? Perhaps,

to blame is the "evil eye". Got a headache? Not

quite feeling up to par? Business not going too well? Perhaps,

to blame is the "evil eye".

To a Westerner, the "evil eye" may sound like something

out of a goofy 1950s horror movie.

But to Azerbaijanis and others living in the Middle East and

Eurasia, the concept is quite tangible. People who are jealous

of you, your accomplishments or possessions are thought to have

the power to harm you just by wishing you evil. Despite the enormous

efforts of the Soviets to rout out traditional practices that

were considered superstitious, they never entirely managed to

rid the society of the belief in "the evil eye".

If you aren't convinced, visit some Azerbaijani homes. Inside

the front door, glance up above the door frame and you're likely

to find what is called "camel's needle"(Alhagi Camelorum)

- a dried out stem of thistles - or some other sort of good-luck

talisman.

Although most Azerbaijanis cannot be said to be superstitious

and, in fact, are really quite European in outlook and world

view, many still use charms to ward off bad luck. "Just

in case", they tell you, when you point out the contradictions.

Since some of the most common antidotes to counter the effects

of the evil eye can be purchased in the open markets, we went

there and interviewed some of the market vendors to find out

how widespread some of these beliefs and customs are.

_____

This past summer in one of the villages near Lankaran, close

to the border with Iran, the shadow of the evil eye passed over

an Azerbaijani wedding. Word had it that the village girls were

jealous of the bride from Baku who had snatched up a local boy

- a valuable catch. Rumors circulated that the local girls had

put the evil eye on the new bride.

The wedding took place back in the village. Once the bride heard

of the curse, she was troubled despite the fact that her family

scoffed at it. The bride was concerned that the spell might affect

her if she partook of any food or drink. Even though her family

didn't hold to such beliefs regarding the alleged "jadu"

(witchcraft), the bride was extremely uneasy. And so she sat

there all dressed up in her white wedding gown, veil and red

sash, refusing to touch any food or drink, all afternoon and

evening.

The Evil Eye

What exactly is the evil eye? Depending on who you ask, you're

likely to get different answers, but most Azerbaijanis agree

that you don't want to get in its way. This could happen if you've

made others jealous of you or of something that belongs to you.

If something unfortunate follows, some Azerbaijanis interpret

it as the work of the evil eye. It's also possible for another

person to bring harm unintentionally by complimenting you.

The belief is so widespread

that some Azerbaijanis refrain from complimenting the parents

of a newborn child. They wouldn't want to blamed if something

bad happened to the child. For this reason, some traditional

families keep mother and child in seclusion for the first 40

days after the birth. Only closest relatives get the chance to

see them. The belief is so widespread

that some Azerbaijanis refrain from complimenting the parents

of a newborn child. They wouldn't want to blamed if something

bad happened to the child. For this reason, some traditional

families keep mother and child in seclusion for the first 40

days after the birth. Only closest relatives get the chance to

see them.

Left: At the Pasaj Bazaar,

Baku. A vendor displays his wares: lemons, parsley, yogurt and

small blue beads to ward off the "evil eye". Photo:

Blair

Some say you can even bring the evil eye upon yourself. For instance,

if you're proud about some accomplishment or become the envy

of others, then if you suddenly feel tired and drained of energy,

the evil eye is blamed. "Ozumun ozume gozum deydi,"

meaning "I brought the evil eye on myself."

Sure-Fire Protection

There are various prescriptions and remedies that are said to

protect against the evil eye. One of the most popular and ancient

ones is a plant called uzarlik (Peganum harmala). Farid Alakbarov,

one of Azerbaijan's foremost medical historians, notes a reference

to it in the 18th-century work "Tibbi-Jalinus" (The

Medicine of Galen). There an anonymous Azerbaijani source recommends

the following: "Take the right eye of a hyena and put it

in very strong vinegar for seven days. Then boil it and place

it close to uzarlik. No evil eye whatever can harm you. From

now on, you have to be bold. Don't be afraid of any witchcraft."

In modern times, uzarlik is still sold in the marketplace and

burned to ward off the evil eye. It costs 1,000 manats for one

portion - approximately 25 cents. According to one market seller,

Movsum Asgarov from Lankaran, the effect of the uzarlik depends

on where it has been grown and how it is burned. "My uzarlik

is gathered wild in the Khizi mountains," he says. "It

must be taken from a very remote place, where a rooster's crow

cannot be heard. Then its effect will be even stronger."

The Khizi mountains are located a few hours' distance north of

Baku on the road to Guba.

Asgarov says that his customers burn uzarlik on special occasions,

like after giving birth to a child, after purchasing a new car

or when getting married. "You burn uzarlik and then inhale

the scent," he says. "Also, when people around you

smell this smoke, they are stripped of the ability to cause you

harm. After that, spread the ash on your forehead and neck. That

will banish black energy from your blood vessels."

Another vendor, Afiyaddin from Ordubad, gathers the uzarlik in

the mountains himself. "We burn it and then pour water on

the ash to put out the fire," he says. While burning the

uzarlik, he chants: "Uzarliksan havasan, min bir darda davasan.

Na gadar ki, san varsan - dada, bala javansan." (Uzarlik,

you are air, you are against 1,001 griefs. As long as you exist,

fathers and sons will be young.) When asked if the plant does

any good, he says, "It's just what people say. I think the

main thing is God's will."

Another vendor suggested taking a small handful of uzarlik and

salt and encircling a person's head three times, while saying,

"Uzarliksan havasan, jami darda davasan. Pis gozlari chikhardib

ovujuna salasan." (Uzarlik, you are air, you are against

every grief. Take out evil eyes and put them in the palm.) Then

the uzarlik is cast into the fire and burned.

When asked if the uzarlik works, the vendor tells us, "Yes,

my son is two years old. He's very vulnerable. I took him to

the playground, and somebody put the evil eye on him. When we

came home, the child felt bad and was crying. As soon as we burned

uzarlik, however, he stopped crying."

Burning Seeds

Uzarlik is not the only Azerbaijani remedy for the evil eye.

An ordinary household spice, black cumin (gara chorakotu), is

also said to work against it. Not only are the cumin seeds used

in bread, but some Azerbaijanis burn them with salt, repeating

phrases like: "Oh God, don't let the evil eye harm us!"

or "Let the one with the evil eye lose his own eye."

Atilbatil seeds can

also be burned for this purpose. One vendor who sells them explains

their appeal: "It's mostly young girls who buy them. They

burn an odd number of seeds (7 or 13 or so), and then spread

the smoke around the house to protect themselves against the

evil eye." Atilbatil seeds can

also be burned for this purpose. One vendor who sells them explains

their appeal: "It's mostly young girls who buy them. They

burn an odd number of seeds (7 or 13 or so), and then spread

the smoke around the house to protect themselves against the

evil eye."

He claims that this method works for him.

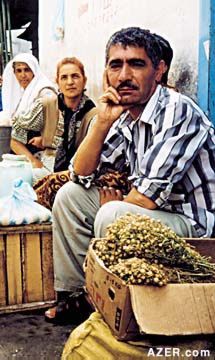

Left:

A vendor

in the Taza Bazaar sells "uzarlik" which is burned

to create an incense-like smoke that is said to ward off the

"evil eye". Photo: Aghayeva

"When I'm out of luck, I burn atilbatil, and then things

go well. I burn it every day - yesterday I burned it twice. I

wrap it in paper, then burn it. When you hear the seeds crack,

it means that the evil eyes have cracked. My grandmother used

it a lot when I was a child, since I was very vulnerable to the

evil eye." Atilbatil is more expensive than the other remedies,

costing 5,000 manats (about $1.25 U.S.) "Only well-off people

can afford atilbatil," the vendor admits.

Camel's Needle

Some plants are hung up instead of burned. For instance, near

the entrance to an Azerbaijani home, you may see a thistle-like

plant called camel's needle (Alhagi camelorum). This plant can

also be found in cars, hanging from the rear-view mirror. Just

like in ancient times, some Azerbaijanis believe that camel needles

protect humans from the evil eye and bring good luck and happiness.

They think that its sharp needles can pierce the evil eye - like

fighting fire with fire.

Yet another form of protection is the daghdaghan tree, which

grows in Nakhchivan. According to one vendor, Afiyaddin from

Ordubad, daghdaghan branches are hung on thread and worn in order

to guard against the evil eye. Its pea-sized fruits are pierced,

threaded and sewn onto clothes or hung as ornaments.

Blue Beads

Several vendors at the market also sell gozmunjughu, small blue

or black glass beads that have a black spot inside a white circle,

resembling the iris of an eye. These beads are tied with thread

and placed around a child's arm. Or, one bead may be safety -

pinned to a child's shirt. Sometimes just a safety pin is worn

with no glass bead.

There are also larger versions of the gozmunjughu, which are

hung in the hall of a home or above a door. One vendor explains,

"People say that when somebody puts his evil eye on you,

these spots fall out or the bead breaks." This is a common

practice in Turkey where belief in the evil eye is quite prevalent.

In fact, businessmen from Turkey are displaying very large evil

eyes in the entrances of their buildings. Take a look at the

new addition at Hyatt Regency, the ISR Tower and some of the

new high rise apartment complexes. One of the most recent samples

of this big blue ornament can be found at the entrance of the

new McDonald's off Baku's Fountain Square.

Left: Near the entrance door of the new McDonald's

on Fountain Square is a large blue ornament to ward off the "evil

eye". Photo: Mastanova Left: Near the entrance door of the new McDonald's

on Fountain Square is a large blue ornament to ward off the "evil

eye". Photo: Mastanova

Better Safe Than Sorry

When we ask the vendors how they knew that these items countered

the evil eye, they just shrug and say, "People say that

they work." But how do Azerbaijanis know that harm was kept

away? How do they know that they would have been harmed by the

evil eye? Perhaps Azerbaijanis don't believe that good times

will always be with them. Being afraid of the evil eye brings

about the opposite of conspicuous consumption in a society. Instead

of trying to show off in front of your neighbor by displaying

more expensive possessions than he does, some Azerbaijanis, especially

the elderly, are more modest, for fear that bragging about their

possessions might cause them to lose them.

When a Westerner "knocks on wood," to convey the meaning

"I hope my luck doesn't change for the worse," the

feeling is much the same. When things are going especially well,

it's only human to feel vulnerable and wonder: "This is

too good to be true. Something is bound to go wrong." Trusting

ancient remedies like uzarlik and camel's needle provides a sense

of security in a precarious world-a world in which history has

proven over and over again that one's luck can reverse itself

without warning.

Jala Garibova, Narges Abadi and Farid Alakbarov

also contributed to this article.

_____

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.3) Autumn 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 8.3 (Autumn 2000)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|