|

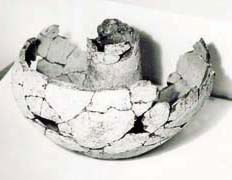

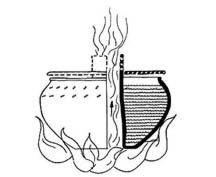

Above left: View of ancient samovar from above. Above right: Side view of the ancient samovar. We discovered an ancient burial mound, 2m deep and shaped in a 3 x 5m rectangle. It held the remains of two humans, a cow, a sheep and 34 pots. First we noticed that the mound had formerly held a wooden platform, or bed. Underneath the rotted wood we found human bones, but not laid out as a complete skeleton. It was as if the body had received what was called a "second burial". Only the main parts were buried: the head, arms and legs. There was a large bronze pin stuck to the skull along with some blue beads. The skull was a bit delicate, so we suspect that it belonged to a woman. She was probably about 30 years old when she died, since her teeth were still in relatively good condition. On top of the wooden platform were the ashes of another person. In ancient times, there was a tradition of cremating wealthy individuals. It is possible that those ashes belonged to such a person who was somehow related to the other person buried there. The skeleton of a sheep lay in the center of the burial mound. Strange as it may seem, all of the pots and utensils that we found were arranged around that sheep. At one end of the mound was the skeleton of either a cow or bull. This skeleton had been smashed into several pieces; we found its head and legs lying quite distant from one another. It looked as if the meat had not been consumed, as if whoever had put it there had just cut it up and buried the pieces in the mound. They may have done this because of a belief that food would be needed in the afterlife. A Startling Discovery While we were examining the area, one of our team members called out: "Tufan muallim (Tufan teacher), Tufan muallim, I've found a samovar!" He pointed to a round object with a tube in the middle [something like an angel - food cake pan]. At first, I couldn't believe that it was a samovar. How could a samovar have been made in ancient times? But after we cleaned it, I noticed that the inside of the tube was sooty, as if smoke had passed through it. The outside of the object was covered with soot as well. It was obvious that the pot had been placed over a fire. After we restored it, I no longer had any doubts - this had to be a samovar. Nor do I think that this object was unusual for its time. Nearly all of the other pots that we found in the mound had the same shape. The only difference was that this particular vessel had a cylindrical tube in the middle. Any of those other pots could easily have been made into samovars, too. Of course, the one we found didn't look exactly like a modern samovar. It didn't have a spigot near its base so that water could be drawn off. Instead, an ancient cook would have poured water from the top of the pot. We don't think that the samovar was used for preparing tea, since tea wasn't brought to the region until the Middle Ages. Perhaps it was used to make soup or broth, or for boiling water for herbed drinks.  Another difference between the design of samovars now and then is that the bottom of today's samovar is closed. You place a burning coal inside the tube. The ancient one was designed to be placed over a fire. Today's samovars have three legs, but this ancient one didn't have any. Instead, people must have put stones underneath it and then built a fire in the center. Left: Sketch of how the ancient samovar would have been used to heat water. One clear advantage that this ancient samovar had over other contemporary pots was that it was much more fuel-efficient. Since it was heated from below and inside, it would have needed relatively little wood or coal. Other Rare Finds We found a number of other interesting items in the burial mound, including several three-legged pots. Their legs imitated the shape of human legs - you can even distinguish knees and ankle bones. This design may have made the legs stronger and less likely to be chipped off or broken. Among the other items in the mound, we were surprised to find three double pots - designed to be used like our double boilers of today. At first we thought they were separate pots that had become stuck to each other in the ground. But after cleaning them, we discovered that they had been designed to fit together - one on top of the other. Also they were more delicate than the other cooking vessels, indicating that they probably were used for special ceremonies - not for everyday use. A three-handled pot shaped like a wineglass also caught our attention. Its clay had been hand-decorated with a four-toothed stone comb, and its handles had flat clay buttons. In the Caucasus, it was once said that a devil could not get into a pot with handles. People believed that the spirits of the dead would come and sit on the buttons and eat and drink from the pot. Perhaps this belief also circulated during ancient times, which would mean that the handles were put there to protect against evil spirits. In any case, they are still a mystery to us. The largest pot in the mound, set next to the skeleton, was made of very dense clay and had a 1 cm hole in a bottom corner. We suspect that this vessel was used to store wheat; the hole would have helped ventilate the grain so that moisture didn't collect and spoil it. It's also possible that the pot was used to hold water or wine. In such a case, something must have been stuck in the hole to keep the liquid from leaking out.

Above left: Contemporary samovars, made of brass, for sale at the Taza Bazaar in Baku. Above right: Three-legged pot found in the Shaki archeological site. Piecing it All Together After we restored the pots, they were brought back to Shaki to a museum belonging to an organization called Ojag (Fire). We couldn't leave them at the Archeological Fund because the conditions there were inadequate for storing artifacts. We didn't want these objects to be spoiled, so we decided to display them in Shaki, close to the location where they were discovered. Unfortunately, we don't have the funding to do carbon dating on the objects to find out exactly how old they are. Instead, we compare them with similar items from other expeditions in order to estimate their age. If the shape, technology and ornamentation are the same, we determine that these objects were all from the same historical period. In the case of the Shaki find, these objects look similar to ones that were found in Armenia and Georgia. These pots are believed to have come from a tribe of Kets that lived more than 3,600 years ago. At that time, this tribe was being formed in the Anadolu region of what is now Turkey. Perhaps there were trade relations or exchange between these tribespeople and other groups living in the Caucasus region. In those other digs, only a few similar objects were found. In the Shaki mound, however, we unearthed many of them. This indicates that the vessels may not have been traded or exchanged; perhaps the tribe produced them on their own. It's possible that this Kets tribe had actually moved to the area now known as Shaki. No matter who created this samovar, I believe it to be the oldest one ever found. It's very rare for any type of samovar to be found; to my knowledge, no others are as sophisticated or innovative as the one we found. It's just one of the many traces of ancient civilization that archeologists often find in Azerbaijan.

Back to Index

AI 8.3 (Autumn 2000) |