|

Autumn 2000 (8.3)

Pages

78-81

"Just a

Cup of Tea"

Sociolinguistically

Speaking - Part 7

by Jala Garibova

and Betty Blair

Come for a cup of tea. Come for a cup of tea.

It's a situation that most foreigners in Azerbaijan can attest

to. They get invited to someone's home "just for a cup of

tea" only to arrive and find an elaborate meal spread out

for them. Though Azerbaijanis tend towards exaggeration and hyperbole

in ordinary speech, when it comes to talking about their own

hospitality, they're inclined toward modesty and understatement.

That casual "cup of tea" may actually have taken hours

to prepare.

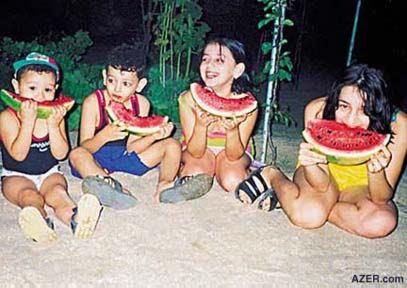

Left:

A "simple"

cup of tea for a guest might also involve a spread of jams, cake,

nuts and chocolate. Photo: Blair

In Azerbaijan it's definitely "who you know" not "what

you know" that makes a person successful. Drinking tea and

entertaining others is an essential ingredient for cementing

and maintaining friendships. When an Azerbaijani complains of

having almost no relations with someone, he may say:

I haven't

even had a cup of tea with him.

Azerbaijanis

have another expression which means, "to have a meal

together."

Literally, "to cut bread"

But the pleasure

comes with obligations. For example, Azerbaijanis complain, "How

could he treat me so badly? We've 'cut bread' together."

There's an expectation of loyalty and commitment once people

have dined together, especially if they have been entertained

at home.

Tea may precede, as well as follow, meals. Tea is served in a

pear-shaped glass. Its unique shape allows the tea at the top

of the glass to cool while the tea in the bottom of the glass

remains hot for quite some time.

Tea is usually offered with thin lemon slices and hard candy.

You'll rarely find it served with milk. And you'll rarely be

served pre-sweetened tea. That's only for kids at breakfast.

In Iran, where an estimated 25-30 million Azerbaijanis live,

cubed sugar is served alongside tea as the preferred sweetener.

Tea is such an integral part of everyday life that Azerbaijanis

take it for granted. Whether the weather is frigid or sweltering,

hot tea is the drink of hospitality. It is offered at anytime

of day or night. In fact, many offices hire a full-time person

to make the rounds serving tea all day long. And even refugees,

who barely manage to put a scrap of bread on the table, feel

bad if they can't offer guests a cup of tea, even if it's very

weak and barely has any color to it.

Always Prepared

But at home, most hosts will offer guests food along with that

cup of tea - unless the visit is short. Even then, baked goods

and cookies, preserves, chocolates and fruit are likely to be

spread on the table. Azerbaijanis have learned to expect guests

at their door any time of day or night, so they always keep some

refreshments stashed away. A good housewife is always prepared.

As for drinks during the meal, they may offer "ayran",

a yogurt-based beverage served cold, or fruit juices, soft drinks

or mineral water. In the Azerbaijan Republic at dinner, alcohol

is likely to be served. Most men drink; most women don't, though

out of courtesy women may clink glasses and join in the rounds

of toasts. The exception for drinking is during the religious

month of Maharram, which commemorates the Shiite Imam Hussein's

death. In Iran, since alcohol is prohibited, drinking is rarer.

Foreigners are usually surprised at the abundance of food that

is spread out on the table.

In the Republic, tables are generally long and narrow, and the

living room usually doubles for the dining room (and, sometimes,

even as a bedroom). The table is absolutely covered with small

dishes so that food is within easy reach of everyone. Never mind

the enormous mess to clean up afterwards!

Seating Order

The most respected person (often the oldest one) is invited to

sit at the head of the table. This is a very conscious act and

everyone understands the social hierarchy, though it may be unspoken.

Come and sit at the head.

If that person

feels that someone else deserves the honor, he will, in turn,

offer the seat to the person he considers more deserving, especially

if someone older is present.

Azerbaijanis are used to lots of guests joining them at meals.

It's not uncommon for 10, 12 or 15 people to be gathered around

the table. Despite the crowded conditions, no one is expected

to sit at a corner edge of the table or they're likely to be

told:

Don't sit at the corner.

To make the

argument more convincing, they might add that any unmarried person

who sits at the corner will never get married.

You will never get married.

Another version could be:

It will be seven

years before you marry.

Literally,

"You'll get married in seven years."

Or, even more

disconcerting:

People who come to ask for your hand will be refused.

This implies that someone will want to marry you but your

parents will not grant permission.

Sometimes a married person will even offer to change places with

an unmarried person stuck on the

corner. Of course, many

people consider this a joke, but others take it quite seriously. corner. Of course, many

people consider this a joke, but others take it quite seriously.

Serving Guests

In most families, when food is brought to the table, the oldest

woman (a grandmother, mother or mother-in-law) serves up the

plates. Guests generally wait for an older person to start eating

first. The host is likely to urge his guests to begin eating

by saying:

Don't let it get cold.

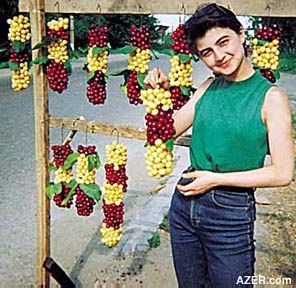

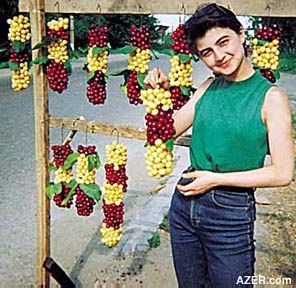

Left:

Traditional

way of selling cherries at roadside stands. Photo: Blair.

He may also say:

Good appetite, equivalent to the French phrase "Bon appétit."

The same expression

may be used when an Azerbaijani runs into a friend or acquaintance

eating at a restaurant or in someone's home.

Second Helpings

It's not unusual for a host to urge guests to eat more and more

food. An Azerbaijani proverb says:

The guest will never say, "I'm full."

It is assumed

that the guest will be too shy to help himself, so the hosts

continuously watch when plates get empty and automatically dish

up more food unless you stop them. If the guest doesn't want

to eat any more food, he can say:

Thanks, enough. I won't be able to eat more.

I've had food at home as well, so I'm not hungry.

If the guest should want more food, he may say:

It's very tasty.

I want to try this one, too.

It's also expected

that guests won't just "eat and run". Even though meals

may last three or four hours - even at lunch, if you're a special

guest. Of course, now that Azerbaijan has gained its independence,

people are much more time-conscious than in the past. They don't

have as much leisure time. When Azerbaijanis need to leave early,

they sometimes excuse themselves by saying:

We're like Lazgi guests-leaving as soon as we've eaten.

Lazgins are

natives of Daghestan, a part of the Russian Federation on the

northern border of Azerbaijan. Lazgins have the reputation of

being very time-conscious.

Thanking the Host Thanking the Host

At the end of the meal, guests say:

Thanks. May God make it [the food] more.

May your table (literally, tablecloth) always be spread open.

Meaning, may you always have food in abundance.

Satisfaction

for the meal may be expressed by saying:

It was very tasty.

It was very delicious.

Guests compliment

the cook by saying:

May your hands and arms be healthy.

After finishing

the food, besides using the expression

, (Many thanks),

some people - especially the elderly - say: , (Many thanks),

some people - especially the elderly - say:

(Thank God), we ate and are no longer hungry. May God feed

those who are hungry.

(Meaning, those in real hunger and need).

Leftovers from

a meal may be sent home with guests, especially if a member of

the family was unable to attend, such as a child, an older relative,

a pregnant woman or someone who is sick.

When food is served at a funeral, the phrase  (May

God accept it) is more likely to be used instead of "Thank

you." This is because food at a funeral is considered

to be offered as "ehsan", the funeral meal,

or for those who are poor. This phrase implies God's acceptance

of this gesture. (May

God accept it) is more likely to be used instead of "Thank

you." This is because food at a funeral is considered

to be offered as "ehsan", the funeral meal,

or for those who are poor. This phrase implies God's acceptance

of this gesture.

Sacredness of Food

Azerbaijanis view food as sacred, especially the natural produce

grown from the earth. It's not unusual for older people to encourage

young people to start their meal:

In the name of God.

They usually acknowledge that the meal is finished by saying

(many thanks,

implying thanks to God). (many thanks,

implying thanks to God).

Food prepared from dough is especially viewed as sacred. It's

not unusual for an Azerbaijani to stop on the sidewalk or street

to stoop and pick up a piece of bread and place it on a windowsill

or some place aside so that it won't be stepped on.

Azerbaijanis have a special expression to identify an ungrateful

person:

The one who steps on bread.

Or they may

convey the same ungratefulness by saying:

He has bread on his knees.

Generally, stale

bread is not thrown away. Instead, it is placed in plastic bags

and set in a conspicuous place outside the entrance of the home

or apartment so that other people know to take it for their cattle

or poultry.

Table Manners

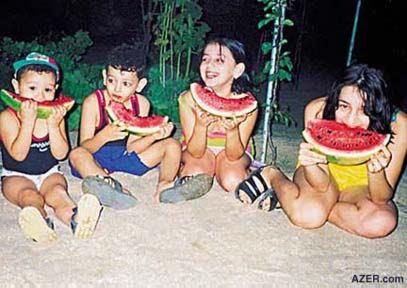

Parents work hard to teach their children appropriate table etiquette.

They consider it very rude if children are greedy or are unable

to hide their hunger or need in front of others. Note the popular

Azerbaijani proverb:

Even let God know you eat pilaf.

Pilaf is considered

the most luxurious of meals. In the Republic it is reserved on

special occasions - weddings, banquets, special dinners, though

in Iran, Azerbaijanis are likely to eat rice dishes everyday.

So the proverb suggests that you should even hide your needs

from God and keep them to yourself. Children usually are warned

not to reach for anything at the table or to taste anything before

it is offered.

Parents urge children not to leave food on their plates. Sometimes

they'll say:

You're not going to be pretty / handsome if you leave food

on the plate.

Your fiancé won't be good-looking

If a child leaves

a piece of bread uneaten, he may be reprimanded:

Eat it up. Otherwise it [the bread] will be chasing you your

whole life.

If you leave this piece of bread, it will cry.

Clearly, food

and hospitality are central to Azerbaijani culture. It is synonymous

with social gatherings. It's hard to imagine having good times

without good food there. That's just the way things are in Azerbaijan.

As a foreigner living or visiting the country, no doubt you'll

have countless invitations to experience it when you stop by

for "just a cup of tea!"

Nush olsun! Enjoy!

Jala Garibova has a doctorate in

linguistics and teaches at Western University in Baku. Betty

Blair is the Founding Editor of Azerbaijan International

and also of the new WEB site, AZERI.org, where the entire

archives of this "Sociolinguistically Speaking" series

may be accessed.

_____

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.3) Autumn 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 8.3 (Autumn 2000)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|