|

Autumn 2001 (9.3)

Pages

32-39

Challenging

the Monsters

Dissident

Painter Rasim Babayev (1927-2007)

by

Jean Patterson

During the Soviet period, artist Rasim Babayev, 74, expressed

his contempt for the government by depicting its leaders as fierce

monsters, or "divs", as they are known in Azeri. In

a recent interview, we asked him to describe the pressure that

he and his fellow artists faced under the scrutiny and expectations

of the Soviet system.

Now that Azerbaijan has had ten years of independence under its

belt, Babayev's own approach to art has changed accordingly.

Left: "Red General" reflects Rasim

Babayev's impressions of the Soviet military complex when his

son was doing military service in the 1980s. Rasim's works are

among the most vivid in their depiction of the differences between

the Soviet (1920-1991) and post-Soviet periods (since 1991).

Enjoy more of his paintings at AZgallery.org where the works

of more than 115 Azeri artists are on exhibit. Left: "Red General" reflects Rasim

Babayev's impressions of the Soviet military complex when his

son was doing military service in the 1980s. Rasim's works are

among the most vivid in their depiction of the differences between

the Soviet (1920-1991) and post-Soviet periods (since 1991).

Enjoy more of his paintings at AZgallery.org where the works

of more than 115 Azeri artists are on exhibit.

He still

feels the pull to focus on Azerbaijan's problems, yet he no longer

has to deal with so many "divs" that used to get in

his way. We chose to feature Rasim's work because it always reflects

a political consciousness - no matter what system rules the country.

"Divs"

are about as ugly as monsters can get - at least the way Rasim Babayev (1927-)

paints them. They're huge. Humans cower beneath them. They have

long claws and sharp teeth. They're vulgar, grotesque and brutish.

In Azerbaijani folktales, they like to eat people, especially

children.

Paintings of

these ferocious divs surround the doorway to Rasim's apartment

studio, from floor to ceiling. Inside there's a gentle, sensitive

artist surrounded by a lifetime of art depicting the political

eras he has lived through.

The div, which might be called Rasim's mascot, became an apt

metaphor for the repressive Soviet system. "The div became

a symbol of evil in my paintings - the symbol of dictatorship,"

he says.

Divs are savage,

callous and unconcerned about what happens to the people who

get in their way. Azerbaijani children may see the div as just

another scary monster, the stuff of nightmares. But for the adults

who look at Rasim's paintings, the div brings to mind the fear

and suffering that the Soviet people experienced at the hands

of their leaders.

"There

are still many problems in our nation, but they are different

now. Admittedly, there are fewer 'divs' (monsters). We have freedom,

but so often we don't really know how to use it."

- Rasim Babayev

(1927-2007)

Targeting the System

"My idea of painting the div came from fairy tales,"

Rasim recalls. "My grandparents and my father used to tell

me those stories. I didn't really understand what the div was

back then. They used to tell me that it was some kind of giant

creature, a monster."

In 1957 Rasim received an order from a publishing house to illustrate

a children's book called "Jirtdan." This fairy tale,

with a story similar to that of "Hansel and Gretel",

is very popular among Azerbaijani children and has been passed

down from generation to generation. It tells how a small child,

Jirtdan (Tiny), outwits a powerful, scary monster (a "div")

that loves to eat children. "Jirtdan is just a guy, a young

child," Rasim explains. "He's a very small person in

the society. But he is quick, he is clever. He outwits the div."

Inspired by the image of this creature, Rasim went on to paint

many more of them during the 1970s. In his paintings, the divs

are shown with gnashing teeth, flared nostrils and threatening

stares. Some have many heads or many arms, another sign of their

power. "Red General", which he painted when his son

was recruited into the military, shows a div in a military uniform,

armed with a set of sharp, pointed teeth.

Rasim's protest against

the Soviet government made him a rarity among Azerbaijani artists.

Others may have shared his feelings, but few dared to express

them. "Ever since I was young, I couldn't understand the

Soviet system," Rasim says. "I never liked it or approved

of it. I don't think that anyone - especially a creative person

- can accept a

totalitarian system. Even an ant seeks freedom. It's only natural.

That's why most of the things I painted were against the system.

The div itself was a symbol of that system for me." Rasim's protest against

the Soviet government made him a rarity among Azerbaijani artists.

Others may have shared his feelings, but few dared to express

them. "Ever since I was young, I couldn't understand the

Soviet system," Rasim says. "I never liked it or approved

of it. I don't think that anyone - especially a creative person

- can accept a

totalitarian system. Even an ant seeks freedom. It's only natural.

That's why most of the things I painted were against the system.

The div itself was a symbol of that system for me."

Pressure on Artists

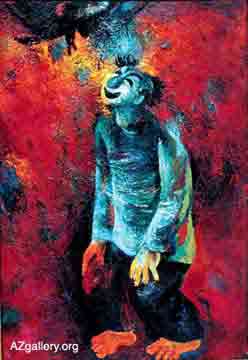

Left: "The Happy Wanderer"

(oil). Socialist Realism in Soviet art required that the artist

portray only uplifting scenes with happy, contented people. This

work by artist Rasim Babayev could be interpreted to be following

the letter of the law, but in essence he may really have been

trying to convey how naive and unthinking such an approach really

was.

Soviet

leaders believed that art had the power to propagate Communist

ideals. They mandated that artists paint according to the style

of "Socialist Realism". Art was supposed to glorify

workers and the progress of industry. It had to be "realistic",

demonstrating that life under the Soviet system was good and

that workers were cheerful and contented, happy to be struggling

for the welfare of the state. Paintings that depicted depressing

or dismal scenes, no matter how realistic, were not allowed to

be exhibited.

To encourage the artists to create this type of propaganda, the

Artists' Union provided them with apartments, studios and special

privileges. Often, the artists would all be housed together in

a single building. While it may seem like the state was building

a creative environment for the artists, Rasim thinks that this

arrangement actually helped the government keep an eye on them.

"At first glance, if you don't scrutinize the idea very

much, this practice seems like a normal thing, or maybe even

a good thing -

the Soviets were taking good care of their artists. But if you

delve deeper, you realize that something was wrong. Not just

something -

everything was wrong. The government controlled the artists,

even on an everyday basis. Is it possible for independent art

to develop under such circumstances?"

Left: "My Grandmother's House"

(Oil on canvas, 180 x 200 cm, 1970s). During the early 1920s,

the Bolsheviks confiscated the homes of thousands of people.

Artist Rasim Babayev depicts the government as monsters stripping

his grandmother of her property. Left: "My Grandmother's House"

(Oil on canvas, 180 x 200 cm, 1970s). During the early 1920s,

the Bolsheviks confiscated the homes of thousands of people.

Artist Rasim Babayev depicts the government as monsters stripping

his grandmother of her property.

The

artists were like slaves, he adds. "The government wasn't

afraid to keep the artists together. It's easy to keep slaves

- just give them

something to eat and drink and they will always be slaves. But

don't dare neglect them or give them less to eat. That's when

the slaves rebel."

Rasim himself rebelled against this type of slavery, joining

the ranks of dissident Azerbaijani artists like his cousin Javad

Mirjavadov, Ashraf Muradoghlu, Tofig Javadov, Gorkhmaz Afandiyev,

Kamal Ahmad and sculptor Fazil Najafov. Many of these artists

were less respected and had difficulty making a living, but they

stuck to their belief that artists should interpret social issues

and express their own artistic visions, not bow to the restrictions

and demands of the state.

Commissions

Since Azerbaijani artists weren't allowed to sell their works

during the Soviet period, they were largely dependent on jobs

that were commissioned by the State. These assignments included

portraits, placards and posters for themed exhibitions. For a

sports exhibition, for instance, posters about sports would be

exhibited.

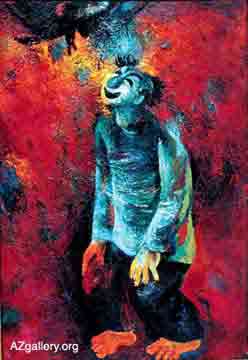

Left: "Divs" became a symbol for

Babayev of what he considered to be the monstrous political system

of the USSR. Left: "Divs" became a symbol for

Babayev of what he considered to be the monstrous political system

of the USSR.

One

exhibition in the 1970s was dedicated to Lenin's 100th Jubilee.

By that time, after the Khrushchev "thaw", artists

didn't live under as many restrictions. "I remember I drew

a picture for the Jubilee called 'For Whom the Bells Toll',"

Rasim recalls. "It showed the gravestones of the nearby

Sufi Hamid cemetery. I was standing in the picture, too. I was

trying to say that everything comes to an end, and that the Soviet

system would come to an end, too."

At the time, Rasim was widely criticized for his controversial

work. One artist said, "Look at this, we're celebrating

Lenin's 100th Jubilee, and he's drawn a graveyard." In fact,

Rasim was showing the people that Lenin had killed.

Many of the State's orders and commissions were doled out to

"People's Artists", those artists who had been officially

recognized for their efforts. "For instance, the State farms

or collective farms would say that they needed ten nature pictures,"

Rasim explains. "The artist would draw them, and then the

Artists' Union would have to give their approval. Then the pictures

would be taken to the farms."

In terms of regular financial support from the government, People's

Artists received twice as much as regular artists did. "That

group of slaves -

the People's Artists and Honored Artists - didn't understand or even imagine

that there could be independent art. The state provided them

with a car, a house, a studio, a telephone. Some were even chosen

as deputies in the Parliament. They were given major contracts.

In general, the government would do whatever they wanted."

In return, those favored artists had to follow orders and submit

to pressure from Soviet leaders.

Early Influences Early Influences

Left: "Wreath of Spring"

(oil). Rasim Babayev's works have changed dramatically since

the collapse of the Soviet Union. Now he indulges in the light

subtleties of pastel shades compared to the heavy dark primary

colors that used to fill his canvases.

Even

before he became an artist, Rasim was aware of the evils of the

Soviet system. When he was five or six years old, his grandmother

told him the story of how her home and property had been confiscated

by the Bolsheviks.

"This happened in the 1920s, before I was born," Rasim

tells. "My grandparents owned several stores. They sold

kitchen utensils and were doing trade back and forth with Moscow,

St. Petersburg, Warsaw and other European cities.

Their store was on Zevin Street, where an art gallery is now.

Today it's called Aziz Alizade Street [off Fountain Square].

She also had a home in Baku, on Sheikh Shamil Street. But when

the Soviets came, they took it all away. She became a refugee,

you might say, in her own Motherland."

Rasim says that his grandmother's story has influenced his painting

in a profound way: "I knew about my grandmother's life and

her unhappiness. How else would a person feel in such a situation?

My grandmother used to say that Soviet power had pushed her into

the corner. How could I not be affected by that?"

In the 1970s, Rasim painted "Grandmother", which shows

an old woman standing in her doorway surrounded by angry divs.

The monsters are taking her home away from her. "My grandmother's

house was confiscated by Soviet power," Rasim says about

the painting.

Now that Azerbaijan is independent, some of his grandmother's

property has been returned to the family. In fact, Rasim's sister

lives in one of the buildings today.

Study in Moscow

In 1949, Rasim went to Moscow to study at the Art Institute.

Nearly every day, he would visit the Pushkin Fine Arts Museum

to look at its permanent collection of works by Rembrandt, Michelangelo

and Rafael. "It was a revelation to me to see them,"

he says. "But then they closed the museum down because it

was seen as glorifying Western art."

To make matters worse, the museum was then turned into a display

of the gifts that world leaders had given to Stalin on his 70th

birthday. "It became Stalin's personal museum," he

says. "That was when I began to see the manipulation of

art first-hand. How could I not protest after seeing things like

that?"

During his study at the Art Institute, Rasim repeatedly thwarted

the expectations of his instructors. "I began protesting

at the Institute," he tells. "I didn't fit in with

the program because I was painting in a different style. The

colors were not conventional and the body lines of my figures

were not realistic."

Left: "Crying Angel" ( oil on canvas),

160 x 128 cm, 1997. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Rasim

Babayev has begun painting angels; however, that doesn't mean

they are free of worry and stress. Left: "Crying Angel" ( oil on canvas),

160 x 128 cm, 1997. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Rasim

Babayev has begun painting angels; however, that doesn't mean

they are free of worry and stress.

In his

third year, Rasim was almost expelled for his unorthodox paintings.

"The Rector told me, 'You can't paint. You just spread the

colors around and don't actually show what you are trying to

represent.'"

Rasim studied at the Institute for six years but never received

his diploma. The school's committee failed him on his final project

because the people in the painting didn't look "Soviet"

enough. So Rasim returned to Baku without his degree.

Six or seven years later, Rasim ran into the Institute's Rector

at the Artists' All-Union Congress held in Baku. By that time,

Rasim was a member of the Artists' Union in Azerbaijan and the

Artists' Union of the USSR. The Rector told Rasim that he was

welcome to go and pick up his diploma, but Rasim wasn't interested.

"I told him, 'I'm leaving it for you. I don't need it anymore.'"

Censorship

The pressure continued. In 1967, Rasim's exhibition in Azerbaijan

was closed down after only half an hour. He recalls: "The

officials shut down the exhibition right away because the works

were not in the spirit of Socialist Realism."

Left: Rasim Babayev has always perceived of

life as complex with many nuances and shades, not simply black

and white. This recent post-Soviet work was inspired by early

Turkic script. Left: Rasim Babayev has always perceived of

life as complex with many nuances and shades, not simply black

and white. This recent post-Soviet work was inspired by early

Turkic script.

KGB

agents would screen Rasim's exhibitions before anyone else had

a chance to see them. Works that were deemed too controversial

were taken away before the exhibition opened. For instance, at

Rasim's own personal exhibition in Moscow in 1976, nine works

were excluded.

Rasim objected, but the officials were adamant. "The Secretaries

of the Artists' Union of the USSR told me that if they didn't

exclude those works, then there wouldn't be an exhibition at

all. I asked if these works were able to destroy the mighty Soviet

Union. They said no, but that it would be better to exclude them.

Otherwise, there wouldn't be any exhibition. So I had to take

them out."

Rasim was not well liked by the KGB. "Once, during the Soviet

period, one of the workers from the KGB asked me why I protested.

I told him that I didn't know of any artist who didn't protest.

Like our poet Nasimi said: 'There's enough room for two worlds

inside me, but I myself can't find enough room in this world'

Poets like Seyid Azim Shirvani and Sabir were protestors. Why

shouldn't I be able to protest? If somebody doesn't like my work

- so what

- they shouldn't

look at it. Of course, I couldn't say that back then."

Hard Times

During the Soviet period, it was difficult for dissident artists

like Rasim to survive financially. "I had difficulty selling

my works," he remembers. "It wasn't so much that people

were afraid to display my works in their homes. Simply, artists

were prohibited from selling their own works. Today I sell my

works fairly easily.

"I remember that

there was a person who "I remember that

there was a person who

came from Germany. He had a very significant collection and wanted

to buy some works from me. He told me that he could pay me with

foreign currency. But I was afraid to sell anything because I

didn't want the Soviets to think that I had a private business

going on the side. You couldn't do things like that back then

- everything had

to be done officially. So I told him that I would just give the

work to him. And that's what I did."

Occasionally, Rasim would be forced to work on state orders just

to pay the bills. "I had to do it," he recalls. "When

you have no other choice, you have to do something. You can't

keep borrowing money. You have to pay back your debt. I had a

family and two children. That's why I had to go to the Artists'

Union and get some works from them."

When Rasim worked on these commissions in his studio, he used

to turn his other paintings around to face the wall, almost as

if they had eyes to reproach him. "It was like I was hiding

them from myself," he says. "I would do those commissions

on a separate table and even use a separate palette of paints.

I didn't want to destroy the purity of what I had been working

on myself. It was like I was trying to fool myself."

Above: "Khanim" (Lady),

oil on canvas 120 x 100, 1993.

Life as a Dissident

In the 1960s, during the Khrushchev "thaw", artists

were given slightly more freedom. Controversial works like Rasim's

were not banned completely. In fact, people who were visiting

from foreign countries would be taken to Rasim's studio to see

his Primitivistic style, to be convinced that Soviet artists

were being allowed to paint in their own styles. "That's

why they didn't touch me," Rasim says.

Still, as an Azerbaijani

dissident, Rasim was not respected. "When I was living in

Russia, the dissidents there looked down on Azerbaijani dissidents.

They didn't take us seriously. It's difficult enough to be a

dissident, but being an Azerbaijani dissident was even more difficult.

There wasn't much support from the other dissidents." Still, as an Azerbaijani

dissident, Rasim was not respected. "When I was living in

Russia, the dissidents there looked down on Azerbaijani dissidents.

They didn't take us seriously. It's difficult enough to be a

dissident, but being an Azerbaijani dissident was even more difficult.

There wasn't much support from the other dissidents."

Left:

Rasim Babayev

with his granddaughter Jeyla, 10, surrounded by his works in

his studio which is located in a building full of artists' studios

not far from the Hyatt Regency hotel.

New Struggles

Now that Azerbaijan is independent, artists have even more creative

freedom. There are no government censors to tell them what they

can and cannot paint. There is still an Artists' Union to help

artists, but it is independent from the government and doesn't

have the large budget that it once did.

"The pressure that artists felt during the Soviet period

- I'm talking about

my life here -

doesn't exist now," Rasim explains. "It used to feel

like something heavy was hanging over my head.

"Now there's no such pressure from the outside. But the

artist must still have a kind of pressure that comes from inside,

from his or her own inner world. In hindsight, I'd have to admit

that that pressure was good for me. It was like a stimulus. Maybe

I didn't appreciate it at the time. But in the end I got a lot

of satisfaction out of expressing myself despite the pressures."

Another very real pressure for today's Azerbaijani artists is

that they have to find their own market for selling works. It's

difficult to find buyers in Azerbaijan who can afford to buy

art. And many Azerbaijani artists, despite their great talent

and magnificent work, have yet to establish an international

reputation.

Rasim himself feels uncomfortable selling his paintings. "I

hang onto my paintings as long as I can," he says. "They're

kind of like daughters to me. But eventually you have to release

them, just like you have to let your daughters get married."

Changing with the

Times

Rasim says that most Azerbaijani artists who are his age have

either stopped working or are still working in the same style

that they used in the past. Rasim, on the other hand, is always

moving and changing. Even though he's no longer confronting the

Soviet system, he's still very sensitive to political issues.

"I live in this world, so I can't ignore political events,"

he says.

He notices that he doesn't feel the need to paint so many divs

anymore. But they haven't totally disappeared. "I can't

run away from the divs," he explains. "They still exist.

They probably always will. I paint them when I come across them

or when I feel them."

During the past decade since Azerbaijan gained its independence,

Rasim's palette of colors has become clearer and brighter. He

has started including angels in some of his paintings: one angel

is shown weeping for the condition of Azerbaijanis, another offers

a wreath of spring flowers as a symbol of hope. "When I

draw angels, I want to draw heaven," he says. "I haven't

seen heaven, but there are probably monsters there, too.

"Life itself is complex. When I paint, I can't imagine just

black or white; there are many nuances and shades." Rasim's

color palette has changed dramatically. Gone are the heavy blacks

and greys and primary colors, especially the violent reds. "I

always felt the strain of so much stress. How else could I express

my anger and protest? You can't express those emotions with quiet

pastels." Today pastels mostly fill his canvas - especially light turquoise.

Many of his colors seem to celebrate the "coming of Spring".

"There are still many problems in our nation, but they are

different now," Rasim says. "Admittedly, there are

fewer 'divs' now. We have freedom, but so often we don't really

know how to use it. And that's a problem, too. Freedom was given

to us, whether we were ready for it or not. Now we need to find

out how to cherish and protect the freedom that we were dreaming

about all our lives."

For more examples of Rasim Babayev's art, visit AZgallery.org, a Web site for art

lovers organized by Azerbaijan International magazine. This comprehensive

site features more than 1,700 works by more than 115 Azerbaijani

artists. Telephone numbers are listed so that you can contact

the artists directly. Note that Rasim's work "Closed Doors"

is featured on our cover. In the past, his covers also defined

the content of "Verbal

Folklore" (Autumn 1996, AI 4.3) and "Journeys"

(Summer 1998, AI 6.2). Interviews with Rasim can also be found in "Crisis

in the Arts" (Spring 1994, AI 3.1) and "Colors

of the Century" (Summer 1999, AI 7.2).

Visit Rasim in his studio, call (994-12) 38-22-87 (home) or (850)

315-1546 (mobile).

____

From Azerbaijan

International

(9.3) Autumn 2001.

© Azerbaijan International 2001. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 9.3 (Autumn 2001)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|