|

Autumn 2006 (14.3)

Pages

82-90

Pipeline Completed

David

Woodward Reflects on Accomplishments in Azerbaijan

by David

Woodward

1. History

of Azeri-Chirag-Gunashli (1994-2006)

2. History

of Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) Pipeline Project

Finally, Azerbaijan's oil is flowing

to international markets via the Baku - Tbilisi - Ceyhan Pipeline.

Azerbaijan International's editor Betty Blair sat down with David

Woodward, President of BP Azerbaijan and AIOC to reflect on the

enormous project just accomplished. Woodward has been leading

BP's activities in Azerbaijan since 1998. See Blair's interview:

"At the Turn of the 21st Century": AI 7.4 (Winter 1999).

Search at AZER.com

AI: We're delighted to have

the chance to sit down with you again, now nearly seven years

after our initial interview with you in 1999. Well, the pipeline

was finally commissioned this past July 2006 and tankers have

left the Turkish port of Ceyhan and are heading to international

markets. This is the occasion that Azerbaijanis have been dreaming

of for more than a decade. You've played a tremendous role in

all of this, having headed the operations for BP for the past

eight years. Help us understand the scope of this project and

your involvement in it. What's happened since you arrived on

the scene in 1998?

Woodward:

Well, when talking about the project here in Azerbaijan,

people tend to focus on the pipeline [Baku -Tbilisi - Ceyhan,

usually simply referred to as BTC]. Woodward:

Well, when talking about the project here in Azerbaijan,

people tend to focus on the pipeline [Baku -Tbilisi - Ceyhan,

usually simply referred to as BTC].

But the oil and gas developments that we've been involved in

encompass much more than that, although without a doubt, the

BTC pipeline is a very significant development in its own right.

For example, in the Azeri - Chirag - Gunashli (ACG) field in

the Azerbaijan sector of the Caspian, we have undertaken the

major development of the some 16 billion barrels of oil in the

ground.

AI: I don't have a clue how

to even begin comprehending how much oil that is? How does one

imagine what 16 billion barrels of oil looks like?

Woodward: A very large tanker would carry a million

barrels of oil, so we're talking about 16,000 of those giant

tankers full of oil. Without a doubt, it's a huge amount.

AI: How long does it take to fill a tanker with a million

barrels of oil?

Woodward: Normally, it takes a day, but that's

because we fill storage tanks with oil, so it's just a matter

of flowing the oil from the storage tanks into the tanker. There

aren't many fields around the world that can produce a million

barrels of oil a day and fill a large tanker every day.

AI: Those tankers? They're

bigger than a football field, aren't they?

Woodward:

Yes, they're several hundred meters long. They can hold a

huge amount of oil. Eventually, oil from the ACG field will be

filling up one of those tankers each day when our production

reaches its maximum capacity at the end of 2008 / 2009. Woodward:

Yes, they're several hundred meters long. They can hold a

huge amount of oil. Eventually, oil from the ACG field will be

filling up one of those tankers each day when our production

reaches its maximum capacity at the end of 2008 / 2009.

In terms of what we've been doing for the last decade, if we

go back to the 1990s, BP and its partners undertook what was

called the Early Oil Project with the development of Chirag.

It was, in effect, a pilot project.

Above:

Living quarters being installed

on the Central Azeri integrated deck, October 2004

It proved that we could develop

ACG in accordance with international standards - technically,

commercially and environmentally. That project came on - stream

in 1997, and we produced it through a relatively small terminal.

We built Sangachal and began utilizing the Northern Export Route

[via Russia to Novorossiysk on the Black Sea], an existing pipeline

that had been refurbished.

Then

in 1999, we commissioned the Western route, which was both partially

new and partially refurbished.It enabled us to export oil via

Supsa on the Georgian Black Sea coast.By 2000-2001, we had sufficient

confidence that we could operate here in Azerbaijan in accordance

with the standards that we follow elsewhere around the world

and that encouraged us and our partners in AIOC to move ahead

with what we call Full Field Development of ACG, which involves

three major phases of development. Then

in 1999, we commissioned the Western route, which was both partially

new and partially refurbished.It enabled us to export oil via

Supsa on the Georgian Black Sea coast.By 2000-2001, we had sufficient

confidence that we could operate here in Azerbaijan in accordance

with the standards that we follow elsewhere around the world

and that encouraged us and our partners in AIOC to move ahead

with what we call Full Field Development of ACG, which involves

three major phases of development.

Above:

Map showing the route of

the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) Pipeline as well as the parallel

route for the South Caucasus Pipeline from landlocked Azerbaijan.

The blue line is for oil; the red, for gas. The BTC pipeline

crosses three countries (Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey) on its

1768 km journey from the Caspian to the Mediterranean where the

oil is pumped into tankers and sent to world markets. BTC is

the second longest pipeline in the world.

Construction began in September 2002. First Oil began its long

journey through the pipeline on May 10, reaching its destination

at Ceyhan on May 28, 2006. The first tanker sailed away to world

markets on June 4, 2006. Baku expects to be pumping at least

1 million barrels per day of its own oil when its fields are

fully operational

Left: East Azeri topsides installed offshore, 2006 Left: East Azeri topsides installed offshore, 2006

We first focused on

Central Azeri and then moved on to East and West Azeri. Now we're

developing Deep - Water Gunashli. So far we have installed jackets

and topsides for the three Central, West and East Azeri production,

drilling and accommodation platforms. We have also installed

a very major facility we call the Compression and Water Injection

Platform (CWIP), which injects some of the gas that is associated

with the oil back into the reservoir to maximize oil production.

The CWIP will also inject seawater around the periphery of the

field to help displace the oil into the producing well. In 2008,

we'll start up Deep-Water Gunashli with two more platforms and

so altogether Full Field Development will comprise six major

platforms. There will also be a thousand kilometers of flow lines

laid on the seabed to transport the oil and gas from these platforms

to the Sangachal Terminal.

AI: Pipelines on the bottom

of the sea?

Woodward: Yes, we have

a special pipe lay barge that can lay sections of pipe that are

welded together down on the seabed in order to take the oil and

gas from the platforms and transport it ashore.

Above: Left: Ceremony at the Sangachal Terminal

to launch the construction of the BTC pipeline. The presidents

of the three countries through which the pipeline crosses participated

in the inauguration: Left:

Turkish President Ahmet Necdet Sezer, BP's Woodward, Azerbaijan

President Heydar Aliyev and Georgian President Eduard Shevardnadze,

September 18, 2002.

Right: BP's David Woodward at the Caspian

Oil and Gas Exhibition in Baku with Azerbaijan's President Ilham

Aliyev and his wife Mehriban (June 2006)

AI: What size are they?

Woodward: The pipes

lying on the Caspian seabed are up to 30 inches in diameter.

Rather sizeable. The BTC pipeline through Azerbaijan and Georgia

to Turkey, is mostly 42 inches in diameter. It some places, it's

46 inches. Occasionally it narrows down to 36 inches, largely

depending on whether the pipeline is going uphill or downhill.

Left: Launching the construction of the BTC Pipeline.

Left: U.S. Secretary of Energy Spencer Abraham, Azerbaijan President

Heydar Aliyev, Georgian President Eduard Shevardnadze and Turkish

President Ahmet Necdet Sezer. Sangachal Terminal near Baku on

September 18, 2002 Left: Launching the construction of the BTC Pipeline.

Left: U.S. Secretary of Energy Spencer Abraham, Azerbaijan President

Heydar Aliyev, Georgian President Eduard Shevardnadze and Turkish

President Ahmet Necdet Sezer. Sangachal Terminal near Baku on

September 18, 2002

So we've undertaken

this huge oil development offshore. As a part of this, we have

pre-drilled a number of wells before we put the jackets there.

The wells are drilled from a subsea template on the seabed and

then the platform is placed on the top of the pre-drilled wells,

which can be tied back to the platform. This has enabled us to

bring production on more rapidly, rather than starting to drill

the wells only once the platform is in place.

At Sangachal, we've had to build a whole new terminal expanding

the Early Oil Project terminal. Again, we did it in three phases.

We've commissioned two phases already. And the third phase will

come on in time for the Deep-Water Gunashli development. Seen

from the air, Sangachal Terminal is one of the largest terminals

in the world, covering an area of 540 hectares.

Left: David Woodward with President Heydar Aliyev at

the Ninth Annual Caspian Oil and Gas Exhibition and Conference

in Baku (June 2002) This was the last oil exhibition that President

Aliyev attended. He had been the driving force in establishing

this international exhibition and the impetus for its enormous

success Left: David Woodward with President Heydar Aliyev at

the Ninth Annual Caspian Oil and Gas Exhibition and Conference

in Baku (June 2002) This was the last oil exhibition that President

Aliyev attended. He had been the driving force in establishing

this international exhibition and the impetus for its enormous

success

That makes it more than

a couple of kilometers long. Crude oil storage tanks are just

one component of the terminal. We have three new tanks, which

gives us a total storage capacity of about three million barrels

of oil. And then there's the pipeline which starts at the Sangachal

Terminal.

While it is the construction of the pipeline that has received

most of the public attention, more than three quarters of the

project-three quarters of the total investment-centers on activities

upstream. Actually, the pipeline only comprises about 20 percent

or less of the project.

So on the pipeline, there were many issues to resolve. First,

a route had to be selected, then agreements with the transit

countries were negotiated, and engineering and environmental

studies were undertaken. Then financing had to be arranged and

investors secured - that is, we had to find oil companies who

were prepared to put their money into the project and transport

their oil through the pipeline. Only then could the construction

phase commence. That involved purchasing access to thousands

of land plots and transporting 160,000 joints of pipe to location.

At our peak construction, 22,000 workers were working on the

pipeline project. But we managed to arrange it in such a way

that not a single family had to be relocated from their homes.

The pipeline is buried along its entire length and the ground

re-instated to its original condition such that owners can continue

to use it for growing crops and grazing their herds.

BTC is a huge engineering endeavor

in its own right. It's 1,768 kilometers long (nearly 1,100 miles);

it crosses 1,500 rivers and watercourses, 13 seismic fault zones

and mountains nearly 3,000 meters high. It has eight pump stations

along the route.

AI: And you have pump stations

not only to enable the oil to go up the mountains, but also to

help brake the flow when it comes down?

Woodward: First of all, you need pump stations

just to move oil along the line because there is friction inside

the line. Even when the pipeline is horizontal with no incline,

you need pumps to keep the oil moving. But if there is mountainous

terrain, then certainly you need more horsepower and more pumps

to move it uphill. When the oil is flowing downwards, sometimes,

we use a slightly smaller diameter pipe or, if necessary, pressure

reduction stations to slow the velocity of the flow.

Above (Left):

Georgian stamp commemorating

the BTC pipeline route, which runs through Georgia's capital

of Tbilisi

Right: Azerbaijani stamp commemorating the

BTC pipeline route, 2003

There's a difference

of about 2,800 meters - close to 9,000 feet, which is nearly

two miles-between the lowest point and highest point of the pipeline.

We start out from about sea level and cross mountainous terrain

both in Georgia and Turkey before descending to the Mediterranean.

The highest point along the entire pipeline is in northern Turkey

at 2,813 meters. It's really quite rugged there.

In selecting the pipeline route, we had to take into account

many things. One of them was the terrain itself. We needed to

select a route where it was physically possible to construct

the pipeline. Another factor, of course, was the environment.

We tried to avoid the most environmentally sensitive areas and

not disturb them. We also took into consideration where the communities

were located and sought to avoid populated areas.

Security is also an important factor, of course, which had to

be taken into account. So when people ask: "How did you

select the route?", there are many factors that we had to

take into consideration.

For example, there were suggestions that we put the pipeline

along the top of one of the mountain ridges. But if you take

the mountain ridge off to install the pipe, how can you reinstate

that ridge? It's not possible to re-instate a mountain ridge.

So we had to look quite carefully at the terrain. We had to deal

with issues such as where we could safely cross major rivers.

Wherever you put the pipeline, it must remain safe no matter

what the environmental conditions are.

Above (Left):

Inaugurating Central Azeri

production. Left: David Woodward (BP), Natig Aliyev (currently

Minister of Oil), President Ilham Aliyev. February 2005

Right: Azerbaijanis have a tradition of celebrating

the first success of oil in a new well by smearing some of it

on their faces. It symbolizes their hope for prosperity and good

fortune for the future. Left: Natig Aliyev [State Oil Company

of Azerbaijan (SOCAR) President at the time and now Minister

of Energy], President Ilham Aliyev, and BP's David Woodward.

At an offshore ceremony celebrating First Oil at Central Azeri,

February 18, 2005

AI: So you say, there are

13 areas that are seismically active through which the pipelines

passes?

Woodward: Yes. We know that this region of the

Caucasus and in Turkey is seismically very active. It's not a

problem to design a pipeline to be safe in those circumstances,

but you do have incorporate these factors into the design and,

clearly, that's what we've done.

The pipeline is coated along its entire length to make sure it

doesn't corrode. That's on the outside. Inside the pipe, we add

chemicals to the oil to inhibit corrosion and then we monitor

it regularly for corrosion.

Above (Left): Sections of pipe awaiting placement

and welding. More than 150,000 sections of pipe that are each

11.5 meters long were used for a pipeline that extends 1768 km

(nearly 1,100 miles) through three countries. In central Azerbaijan,

summer 2003

Right: A pipe-bending operation on the BTC

pipeline near Kars, Turkey

AI: And the pipe itself is

steel?

Left:

The oil projects in Azerbaijan have resulted in the annual

Caspian Oil and Gas Exhibition, which has been held in Baku every

year since 1994. Here, President Ilham Aliyev addresses the conference

guests at the opening ceremony at the 13th Annual Conference.

June 2006Woodward: Left:

The oil projects in Azerbaijan have resulted in the annual

Caspian Oil and Gas Exhibition, which has been held in Baku every

year since 1994. Here, President Ilham Aliyev addresses the conference

guests at the opening ceremony at the 13th Annual Conference.

June 2006Woodward:

Yes, and you have to keep it from rusting. Externally, we

do that through a coating and something called a cathodic protection

system. Internally, we add a chemical corrosion inhibitor to

the oil and send devices called "pigs" down the line

every few days to sweep water and debris out of the line that

might cause corrosion. We also ran "intelligence pigs"

down the line, shortly after construction and, will continue

to do so about every three years.

This apparatus can measure the

thickness of the pipe walls. So if there is any damage done through

corrosion, or perhaps inadvertently by a farmer, then this can

be detected by the "intelligence pig"

So oil flowing from a reservoir about 2-3 thousand meters below

the seabed of the Caspian passes up through one of our wells

and comes to one of our production platforms.

Then, water is separated from the oil, gas is separated, and

then partly processed, and the oil travels along the seabed flow

lines until it arrives at the Sangachal Terminal.There it is

further processed. Any residual water is removed and the oil

is heated to boil off the residual gases. From there it goes

into storage tanks, then into the pipeline to begin its long

journey to Ceyhan, Turkey, through these pump stations, up over

the mountains, under rivers and eventually to storage tanks at

the terminal at Ceyhan. Every day tankers turn up at the jetty

to fill up with oil and then it will sail off to terminals somewhere

in Europe or even the United States.

AI: And then it goes to refinery?

Woodward: And then it goes off to a refinery.

The refinery will extract the various products from it. Crude

oil is a mix of a whole range of hydrocarbons from light to heavy.

When you refine oil, you are really just distilling it and taking

various cuts.

Some of them will be at the heavy end-the bitumen or tar that

you put on the roads. Some of it will be fuel oil that is consumed

in power stations. Some

will be diesel, gasoline, or even liquefied petroleum gases -

like propane - that is used in camping gear.

It's a fascinating business.

I don't think we do a very good job of explaining to people what's

involved in finding and producing oil and gas around the world.

There's so much technology involved to develop these resources.

Left: Gathered at the Caspian Energy Centre at the Sangachal

Terminal to inaugurate

the completion of the Azerbaijan section of BTC pipeline on May

25, 2005. (From left): Turkish President Ahmet Necdet Sezer,

Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev, Duke of York Prince Andrew

of the UK, BP's Chief Executive John Browne, U.S. Secretary of

Energy Spencer Abraham, and BP's David Woodward Left: Gathered at the Caspian Energy Centre at the Sangachal

Terminal to inaugurate

the completion of the Azerbaijan section of BTC pipeline on May

25, 2005. (From left): Turkish President Ahmet Necdet Sezer,

Azerbaijan's President Ilham Aliyev, Duke of York Prince Andrew

of the UK, BP's Chief Executive John Browne, U.S. Secretary of

Energy Spencer Abraham, and BP's David Woodward

Some of the oil and

gas fields now being found are in offshore waters 10 thousand

feet deep. That's a couple of miles down just to reach the seabed.

And then the field itself might be another 3, 4 or 5 miles down

below that.

Just think what's involved to be able to figure out where oil

and gas is located and then successfully develop it, transport

it to market, refine it and then deliver it every day-day in

and day out-into people's cars or homes and so on.

To me, it's a remarkable achievement which most people take for

granted or they consider it an irritation because they have to

pay $3 per gallon for petrol in the U.S., or $7 in the UK because

of tax, which is still less than the price of mineral water.

AI: When you see how complex

the entire process is, it's really amazing!

Woodward: Unfortunately, people tend to think

of the oil industry as low tech and that high tech industries

are in Silicon Valley [computer technology] or the pharmaceutical

industry. But you should see some of the technology that we use.

We probably use some of the biggest computers and most advanced

computer processing of any industry.

AI: For what kinds of things?

Woodward: Well, for example, seismic data processing.

Vast amounts of data, essentially sound echoes, from subsurface

formations are processed to study the formations under the ground

and identify where oil and gas is most likely to be found. Nowadays,

we can use seismic to determine how oil, water and gas are moving

in a producing reservoir and, hence, optimize the development

of the reservoir and maximize oil recovery.

The oil industry is often perceived as a dirty business that

pollutes and damages the environment. But again, if you consider

how much oil we develop and move around the world, very, very

little of it actually gets spilled into the environment. Every

now and then, there is an accident but we're normally pretty

good at dealing with it. Sometimes it's not the oil companies,

but shipping companies. Increasingly, oil companies like BP are

starting to take more control of the transportation of their

products around the world because we get a bad name if there

is a spill somewhere.

AI: Why did it take so long

to build the pipeline in Azerbaijan?

Woodward: Back in 1998, there were discussions

about the pipeline being up and running in 2001. I came here

at the end of 1998 and at that time, the oil price was $10 a

barrel [now it's $70 per barrel]. We didn't even have a development

plan for Azeri - Chirag - Gunashli (ACG) Full Field Development.

We had not selected the pipeline route. Some people were saying

Baku - Ceyhan [via Turkey] was the best choice. Others insisted

on Baku - Supsa [via Georgia, through the Black Sea down through

the Turkish Straits]. And some promoted Baku - Novorossiysk [via

Russia]

It was probably about the year

2000 before we eventually got agreement from a sufficient number

of partners to be able to pursue the Baku - Ceyhan route. And

that was conditional on our being able to negotiate reasonable

transit agreements with each of the countries - Azerbaijan, Georgia

and Turkey. It was also subject to our being able to engineer

the pipeline at an acceptable cost and to find companies willing

to commit sufficient oil to the pipeline and so on. You don't

build a pipeline of this scale on a speculative basis in hopes

that somebody might use it. You need to have sufficient companies

willing to commit to transport agreed quantities of oil via the

pipeline.

AI: So, actually, the process

of persuading people about all of these issues can take more

time than the actual construction of the infrastructure to develop

oil.

Left: A

team of ecologists examining the BTC pipeline in Southern Turkey.

The pipeline has been buried the entire length of the route and

the ground cover has been restored to its previous condition

before the constructionWoodward: Left: A

team of ecologists examining the BTC pipeline in Southern Turkey.

The pipeline has been buried the entire length of the route and

the ground cover has been restored to its previous condition

before the constructionWoodward:

Almost. The engineering

of the pipeline and, particularly, its construction is relatively

straightforward. That's not to minimize or diminish the many

challenges that were tackled by the construction teams and engineers.

But really the difficult part was in getting a sufficient number

of participants to agree that they were willing to fund it. They

had to be convinced that they would get an adequate return on

their investment.

A key part of this is concluding agreements with the transit

countries - Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey. You must have confidence

that none of the transit countries will suddenly change the terms

once you've made your investment.

Almost two years were spent negotiating the various agreements

with the transit countries before we knew what the basis would

be for building this pipeline if it was going to be built. This

included the transit fees - in other words, the amount that these

countries would charge for each barrel of oil moving through

the pipeline in their country. What tax terms would apply? What

assurance would we have that once the pipeline was actually built,

that the terms would not get changed? Who would be responsible

for the security of the pipeline? And so on.

Once we got all of the agreements, we were able to focus more

on selecting the actual route of the pipeline, the engineering

of it and the cost estimates. In parallel with those decisions,

the partners agreed that they would seek external financing.

So we went to the World Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction

and Development (EBRD) and then to a group of commercial banks

to borrow about 2.5 billion dollars towards the cost of the pipeline.

These banks had requirements regarding the social and environmental

impact of the pipeline. Tens of thousands of pages of documents

had to be submitted to the lenders to satisfy them that everything

was going to be done to the standards that they required. After

that, they would release the money.

So the construction of the pipeline did not get started until

late 2002. It has then taken us about three and a half years

to actually construct, commission and get it into operation.

AI: Which is really quite

fast. Yes?

Woodward: Yes, it is really quite fast when you

consider the scale of the pipeline and all of the technical challenges.

At the peak of the pipeline construction, we had 22,000 workers

working on it. Think about how many camps you must have along

the pipeline route to accommodate all these thousands of workers.

How many meals you have to serve daily. This is a huge operation

in its own right. And those people have to be driven out to the

work site everyday because each camp would have several hundred

or even a thousand workers but they operated over a line length

of 100 kilometers or more. We had to have buses to transport

them out to the work site, get lunches and drinks to them so

that they could function throughout the day, and then transfer

them back to the camps at night so they could get a night's rest.

One tends to overlook such things. The publicity around the pipeline

has, perhaps, had more emphasis on the political dimensions,

the environmental aspects and security. One tends to forget the

enormous logistics, the engineering, and the pure construction

activities - like river crossings. Consider how much effort is

involved in boring a hole the distance of a kilometer underneath

a river.

For example, the width of the Kur River and its flood plain at

the location of the horizontal directional drill crossing (HDD)

in eastern Georgia is approximately one kilometer. The river

itself is about 100 meters wide however the HDD needed to traverse

under the entire flood plain.

AI: And some of those rivers

are deep and quite swift.

Woodward: Oh yes, which is why you have to start

well back from either side of the river banks and bore down at

an angle to a depth of perhaps 10-15 meters below the deepest

part of the river.

AI: How did you finally decide

on the Baku-Ceyhan route?

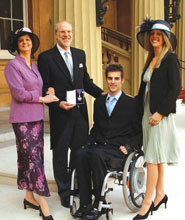

Left: Queen

Elizabeth II congratulating David Woodward after bestowing upon

him the Order of St. Michael and St. George for the tremendous

role he has played in the development of the oil industry in

Azerbaijan for the past eight yearsWoodward: Left: Queen

Elizabeth II congratulating David Woodward after bestowing upon

him the Order of St. Michael and St. George for the tremendous

role he has played in the development of the oil industry in

Azerbaijan for the past eight yearsWoodward:

Ultimately, as far as

we were concerned, it was very clear that the country that had

the resources - Azerbaijan - desired to export its oil to international

markets by a pipeline that went through Turkey and that gave

direct access to the Mediterranean and the world market. Although

we and our partners originally looked at several alternatives;

ultimately, the deciding factor was our desire to align ourselves

with the host country.

Although there was an argument that there were routes that would

have cost less than Baku-Ceyhan; for example, Supsa or Novorossiysk,

there would have required the necessity to go through the Turkish

Straits, which are environmentally sensitive and becoming increasingly

congested with tanker traffic. Taking into account the need to

bypass the Turkish Straits, BTC is a commercially competitive

solution.

AI: What can you tell us about the security of this operation?

Woodward: Security, clearly, was one of the important

criteria for deciding the route of the pipeline, and its design.

We've had a lot of advice from the authorities here in Azerbaijan

and from Western governments. As the pipeline is buried, it's

not that easy to find. The pump stations and facilities that

are above ground have protection along with access control, security

systems and cameras.

We have pipeline patrols along the entire route. Generally, these

patrols riding horseback that are hired from local communities

and who personally know the farmers and shepherds and people

from these areas. So, if someone is inadvertently attempting

to carry out activities too close to the pipeline, the patrols

will remind them to be careful and, of course, they can keep

an eye out for others who might not be as well - intentioned.

We've developed and will continue to maintain good relations

with communities along the pipeline route. We've spent quite

a lot of money on schools, clinics, minor infrastructure. We've

provided micro - financing to assist the development of local

enterprises. We're trying to help these communities build the

capacity to help themselves.

AI: How many communities

are there that are located along the pipeline route?

Woodward: There are several hundred that are in

the "corridor" on either side of the pipeline. We have

community liaison officers who are in contact with the communities

on a regular basis in case they have any issues or concerns about

our activities, so the community can raise them and have them

dealt with. It's very important for us to maintain good relationships

with the people in the proximity of the facilities.

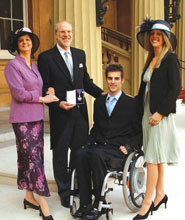

Left: David

Woodward with his family at Buckingham Palace in London after

being invested with the Order of St. Michael and St. George by

her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Left to right: Wife Quinta, David

Woodward, son Mark and daughter Selina. March 29, 2006 Left: David

Woodward with his family at Buckingham Palace in London after

being invested with the Order of St. Michael and St. George by

her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Left to right: Wife Quinta, David

Woodward, son Mark and daughter Selina. March 29, 2006

Beyond that, the government

in each of the countries has the responsibility for ensuring

the security of the pipeline and they have recruited and trained

forces to undertake this task. So there are multiple layers of

security in place.

To change the subject, let's talk about you. Isn't it quite

unusual in BP for one manager to be in the same position for

eight years? Isn't that quite rare?

Yes, it is unusual. And it's

the longest period of time that I've had the same assignment

in my career. These large-scale projects take quite a long time.

As people build familiarity and relationships, there's value

in being able to maintain that continuity.

AI: This is such a huge project. How do you find yourself

different after eight years?

It's worked out for me and my

family that we've been happy to stay here and see these projects

through to completion. I've derived an enormous amount of satisfaction

in being involved in something from the early conceptual phases

all the way through to operation.

As you accumulate experience,

I think you're less likely to view something as a real crisis.

I've seen a fair number of crises over the years and I've had

my share of worries and concerns. Perhaps, I'm less likely now

to panic when problems occur, as inevitably they will. I'm confident

that we can work our way through all the difficulties somehow.

AI: Well, what's next?

Woodward: For BP and the project, this is just

the beginning. We've built these facilities in order to produce

the oil and to export it for decades to come.

And, of course, there's gas, we've got the Shah Deniz Stage 1

project underway. Within the next few months, we'll start up

gas production, which will flow along a pipeline parallel to

the BTC pipeline. It's a separate pipeline but it follows the

same route. Shah Deniz will produce gas, not in liquid form,

but like the air around us. We'll compress it a bit so we can

get more of it down the pipeline.

There will be further stages of development of both ACG and Shah

Deniz as we build the production up to the maximum capacity of

the pipeline. Then there's the potential to expand the pipeline.

An inter-governmental agreement between Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan

was signed in June 2006 and at some stage in the future, Kazakh

oil will almost certainly flow through BTC.

AI: There's no pipeline under

the Caspian right now, so does that mean oil will cross by tanker?

Woodward: Initially, transport will take place

by tanker and then, depending upon the volumes of oil, they may

decide to lay a pipeline on the bottom of the Caspian. More oil

coming from Kazakhstan may well require the expansion of BTC

pipeline. There are various ways by which we can increase its

throughput; for example, some additional pump stations and pumps

might be added to the line. Finally, oil is heading to market

but that's really just the start of things.

AI: And yourself? What are

your plans? Are you staying on?

Woodward: I expect to

move on towards the end of this year. It will be eight years

that I've been here in Azerbaijan. So, it's time for something

different and for somebody else to come to lead the business

here. I'll be retiring from BP and moving on to a new phase in

my life.

[Note: Bill Schrader has since been named as the new President

for BP Azerbaijan who will head the AIOC project starting in

November. See Faces / Places in this issue.]

We've had a marvelous time here but it's been hugely demanding

on my family and one tends to neglect so many other aspects of

life. There are other things in life that I'd like to devote

more time to.

One gets a lot of satisfaction in being associated with something

that is as big and challenging as our projects in Azerbaijan,

but I think the greatest satisfaction has come from the way in

which we have approached each task. We have devoted enormous

care to the environment, to the social impact that the pipeline

has upon communities, to the way that we have looked after the

safety of our workers, maintaining high ethical standards and

by being very transparent about everything that we've done. We've

gone beyond what you might expect a company to do when undertaking

projects of this scale. It's the process - the way we've gone

about it - and the concern we've tried to show for people that

means so much to me.

Of course, there has been some criticism from NGOs [non-governmental

organizations], and the media, But I've always felt that we could

stand up to such scrutiny and challenge because we were confident

that we were doing our job to the highest standard. If valid

concerns were raised then we endeavored to engage with those

concerned to see if we could address their issues and improve

the project still further. I've always felt an enormous genuine

pride in what we have accomplished here in Azerbaijan.

______

Back to Index AI 14.3

(Autumn 2006)

AI Home | Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|